Kathryn Keller’s landscapes at the Moremen-Maloney Contemporary Gallery in Louisville, Kentucky succeed on three scores: they are authentic in conveying a particular geography, they evoke reverie and they bespeak an eloquent silence.

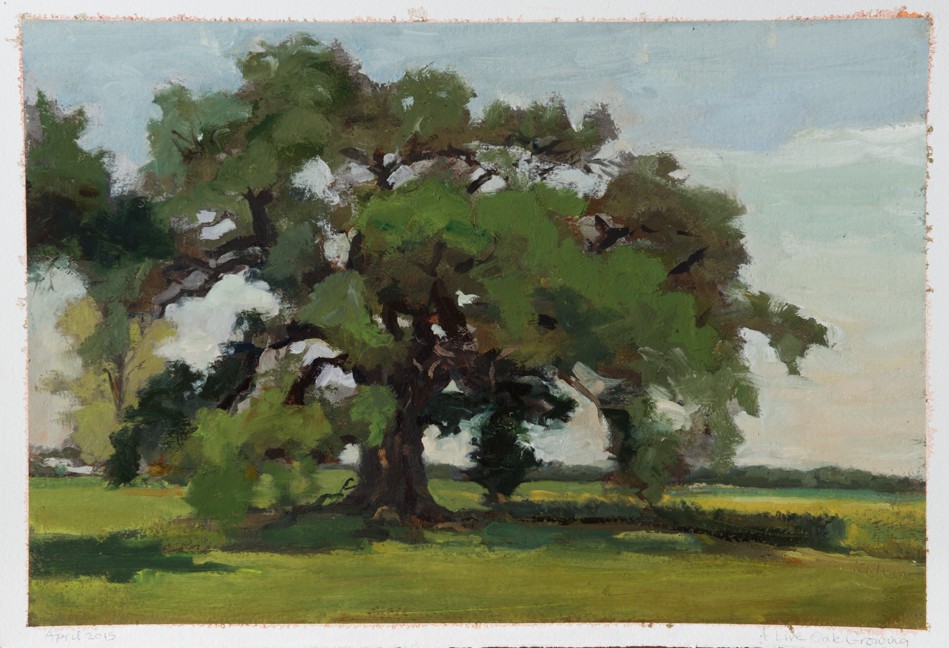

Keller lives near Alexandria, Louisiana, close to the center of the state. This varied sub-tropical flat land, agriculturally a mix of crops and livestock, is Keller’s subject. She succeeds in what poet William Carlos William termed “the achievement of a locus:” her vision is fresh, largely free of clichés, and works a taut balance between observation and the dictates of the oil and watercolor mediums that she employs.

Open fields, groves of trees, and the vagaries of climate and weather share the focus of attention with the flow and drag of a loaded brush against paper or canvas. Mottled passages of black-blue-green foliage fulfill the needs of description as well as calling attention to the moment when pictorial order supersedes realism, balancing abstraction and representation. Despite heavy impasto and forceful application, the paintings are well ventilated with an envelope of atmosphere and transparency of light. This part of the world comes across as Keller’s spiritual turf: she would seem to be of this place, not merely from it.

Of particular note in this exhibition are five studies of the side of a house, the artist’s home. These modest easel paintings (the largest of which is 26″ x 22″), read at first like the everyday moments in the deadpan photography of William Eggleston and William Christenberry. The side-long glancing views, the simplified architectural geometries of windows, chimneys, and rooflines, and the casually foreshortened perspectives connote an easy familiarity with the subject. But on further examination the house is invested with flat built-up surfaces of long continuous paint passages. Shadows that seem more substantial than the building and Rorschach blots of plant life provide psychological comment on life within the inner sanctum. In only one of these studies is an entry to the home depicted.

Prolonged meditation on the subject of house is also suggested by the palette: Bleakhouse Cedars – possibly the most successful of the series – depicts an overcast sky, the building in desaturated tints of gray and yellow, flanked behind by Keller’s black-green foliage, and at the side by an acidic greenish hedge and lawn, painting in elusive variation of olive-algae hues. Overall the muted color chords of faded yellow and gray played against the varied greens convey an intense concentration on excluding everything extraneous to the artist’s narrative.

The result of Keller’s focus in all of her works in this exhibition is a sense of reverie, of something half-remembered, a predigested memory as if the viewer had already been to this home and had rich associations with the place. Keller gives us the first paragraph, and no more, of imaginary short stories echoing William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, Eudora Welty, or Alice Walker.

Quietude and melancholic introspection also come across in works in which two houses are included in similarly reduced views. In Front Porch, a saw-toothed shadow and black windows on the near side of a house lead perspectively to a dwelling in the middle distance beneath a bare tree. Which is the home place? We are not told. Part of the fascination of these works lies in their evasiveness: the density and weight of the bare walls, the status of light, and the air of stillness spark curiosity about the calculated privacy and secrets withheld.

They are elegiac paintings, wrestling with how past informs the present and future (their closest photographic analogy is with the cemetery scenes of Clarence John Laughlin, not the snapshot sensibility of Eggleston and Christenberry). Locked down and contemplative, these are silent pictures: silence as a moment of stopping, as a condition of consciousness, as a cultivated inwardness. Close values and a subdued timbre characterize some other painters of silence: Hammersoi, Morandi, Balthus, Hopper, Reinhardt and Rothko, for example. All share a monastic relinquishing of immediacy and spontaneity in favor or an extended awareness of presence and place.

To return to William Carlos Williams: “It is because we confuse the narrow sense of parochialism in its limiting implication, that we fail to see the complement of the same: that the local in a full sense is the freeing agency to all thought, in that it is everywhere accessible to all…every place where men have eyes, brains, vigor and the desire to partake with others of that same variant in other place which unites us all.”

Kathryn Keller: A Sense of Place, Moremen-Maloney Contemporary Gallery, 939 East Washington Street, Louisville, 40206, through August 31st.