Carleton Wing’s statement on “Sharing Time and Space,†the exhibition currently up at MS Rezny Studio Gallery in Lexington, Kentucky, calls it an “exchange.â€Â As the title also implies, this is something shared. On its surface this is readily apparent: here Wing and Paolo Dal Prá engage in a dialogue even across the gulf between life and death. But the objects also stake out their own positions and their own conversation. The cross between the materials and the bodies of work is also an exchange, one that can even speak apart from the intentions of artist, gallery, or viewer. This is where things become more complicated. Set up together, the works work things out amongst themselves.

At first the juxtaposition of crisp digital collages with rough wood assemblages, rustic clay figures, and heavy dark paintings comes across as uneven and jarring. Yet there is a sense that despite differences in form and material an animated conversation is taking place and affinities are being forged. Wing and Prá’s works are tied together in ways beyond the inconveniences of their contrasting mediums. In a way these works exist like a single thing, each object a part that contributes its specialized function to the organism as a whole. The exchange is symbiotic.

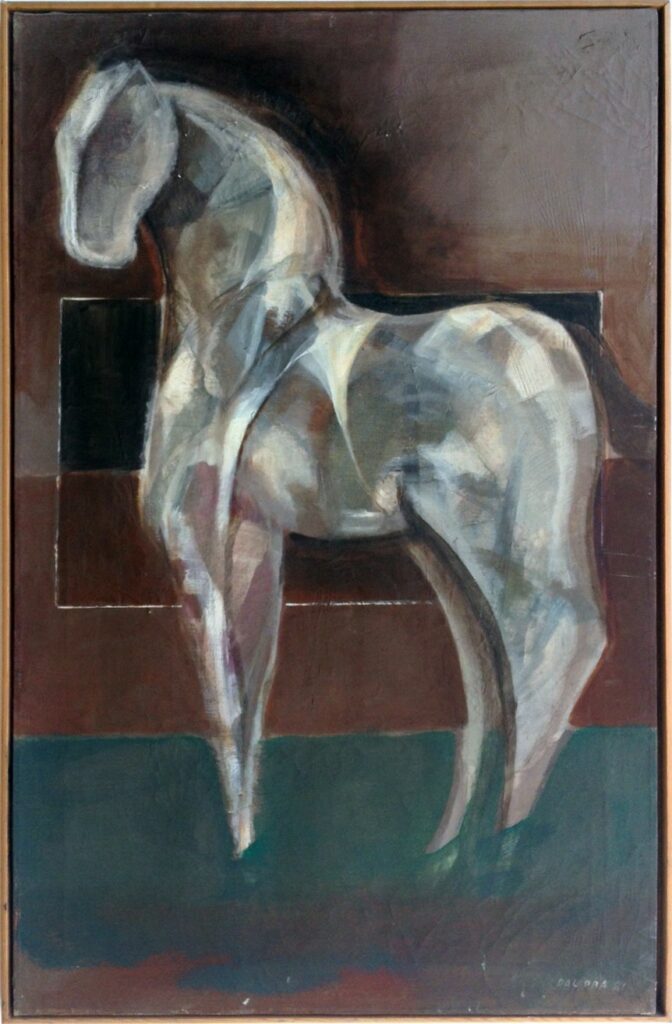

This is one way that the works fill in each other’s gaps. Separately, Prá’s sculptures, paintings, and drawings seem to be disintegrating. But their fragmented appearance is not really a product of being purposefully unfinished or aesthetically rustic. Instead this is the spirit of their “primitivism,†as if they are objects found, compiled, and now left to weather away. Prá’s works come across like some distant memory, a trace or a vestige of some half-remembered experience. The haziness and roughness of Prá’s paintings and sculptures feels like the melding of different realities. A painting like Figure, showing the curvature of the back of a human form breaking across a mottled surface, is like an image whose overall clarity comes at the expense of more specific details. The object itself and its forgotten source trying to push itself back to the surface meld together as one appears to wear away and reveal the other

Following after this same comparison to memory and its workings, Prá’s sculptures are likewise in the midst of a breaking-down. Their disintegrations are much more literal however. They take place in the physical form and materiality of the objects themselves. This nudges them beyond the realm of art objects to that of real things with a real stake in life and death. Inside of the aptly titled Figure are metal and springs, the guts and bones of things with real presence in the world. These objects become more logical and their existence more necessary as they take on a more vital character. The more this vitalism grows the more intertwined these works become.

In this sense there is also a somewhat sinister current that runs underneath and between these works. Where at first they appear to be starkly separate, they are bound together by the unpredictability of anonymity and autonomy. Together they hint at something outside of what can be seen but which regardless looks out and sees. In the case of Wing’s collages, there is a literality to the form he employs. In the sense that each one plays at being a model of the universe, the radiation from the center is in, out, and infinite. Yet they also hint at an almost conscious presence that peers out through the rapid circulation of the mandala form. Like the eye of a storm, the supposed peace at the center of these mandalas barely masks the fear and anxiety of what their forms in fact model.

This is where Wing’s mandalas really set themselves apart. Beyond their mundane source imagery (birds, prawns, onions), Wing’s mandalas are expansive even as they appear to shrink into the limits of their centers. More than attractive designs they are like eyes that look out from each little pinpoint. In the middle of each mandala, the design is pulverized into the smallest and sharpest possible extremity. The more abstract mandalas pull strongest toward the oblivion of their cores. Muskrat Jaw Secular Mandala and Shell Secular Mandala begin on their fringes as recognizable objects but quickly melt into carousels of frantic and chopped up lines and colors. The complexity of the designs ultimately breaks down into the simplicity of the point. Yet this simplicity is misleading. Through the static center the universe comes roaring through.

So this conversation between artists and artworks is quite complex. Initial separation between the objects is bridged by the presence of a vital force that operates seemingly beyond human control. It is interesting that so many of Prá’s figures appear to be blind. But while they are eyeless or with eyes blank and unfocused, they still seem to look out. Even more, placed next to sharply gazing mandalas they are added a profound sense of penetrating sight. Together these works exist as the more unnerving viscera of existence. The universe stares back wildly through the centers of Wing’s swirling and anxious circles and Prá’s mysterious and half-completed figures. When the ghoulish decrepitude of Prá’s Horse plays against the cold prickly apparatuses of Wing’s Machine Part from Tower Bridge, London Secular Mandala, their combined effect is uncomfortable and uncanny. But even here life also flashes in triumph.

In the end it is a fitting memorial. What better place is there to celebrate than within art itself with all its contradictions and persistent questions? Here we are confronted with art as both mute and static objects and something much more active, unrestrained, and messily unresolved.