Richard Avedon’s photograph of the 77-year-old filmmaker Jean Renoir is arresting in its rawness. Avedon is unsparing: his extreme close-up captures the auteur’s rheumy eyes, the furrows in forehead and chin, the haunted expression as Renoir stares off camera. His head is placed just off center in the square composition, adding to the sense of tension.

This strong and unsettling image is one of fourteen in Portraits of the Artist, an intimate exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum organized by Brian Sholis, who came on board there last October as Associate Curator of Photography.

As new kid on the block, Sholis seized the first gallery that came open to present photographs from the museum’s collection and he is making his curatorial debut in ways small and large.

In addition to this show, a year-long public art initiative, Big Pictures, kicked off on June 1. It takes photographs out of the museum and puts them on billboards around Cincinnati—but more about that later.

Artists have always been drawn to other artists—it is not surprising to find painters, musicians, performers of all stripes, as well as other photographers stepping in front of the lens.

In Portraits of the Artist, Sholis makes a point of examining the relationship between photographer and subject and how it affects the resulting image.

Avedon, for example, confessed to being extremely nervous about photographing Renoir, who was not only one of the most influential directors of twentieth-century film, but part of an artistic dynasty established by his father, the Impressionist painter August Renoir. His unease seems to be mirrored on the face of his subject.

Sholis says that he was particularly interested in what transpired when there were famous artists on both sides of the camera. Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis casts a wary—even challenging—look at photographer Lee Friedlander in a striking portrait.

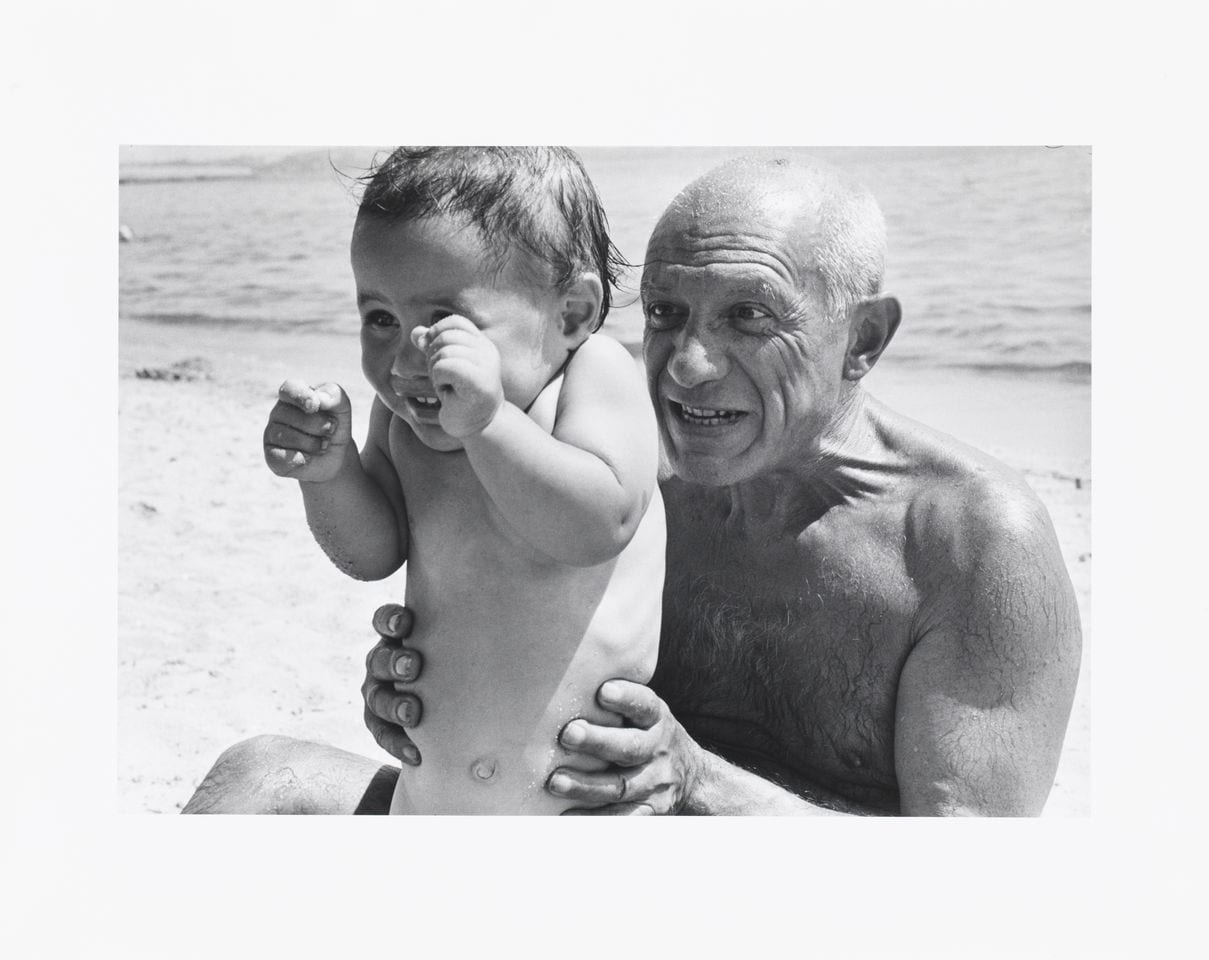

By contrast, a joyous Pablo Picasso, caught at play with his young son, appears entirely unaware of the presence of Robert Capa, who spent a week with the legendary artist. It is a life-affirming image by a photographer best known for his searing coverage of the Spanish Civil War.

Other work explores relationships that lie between two photographs or between subject and photographer.

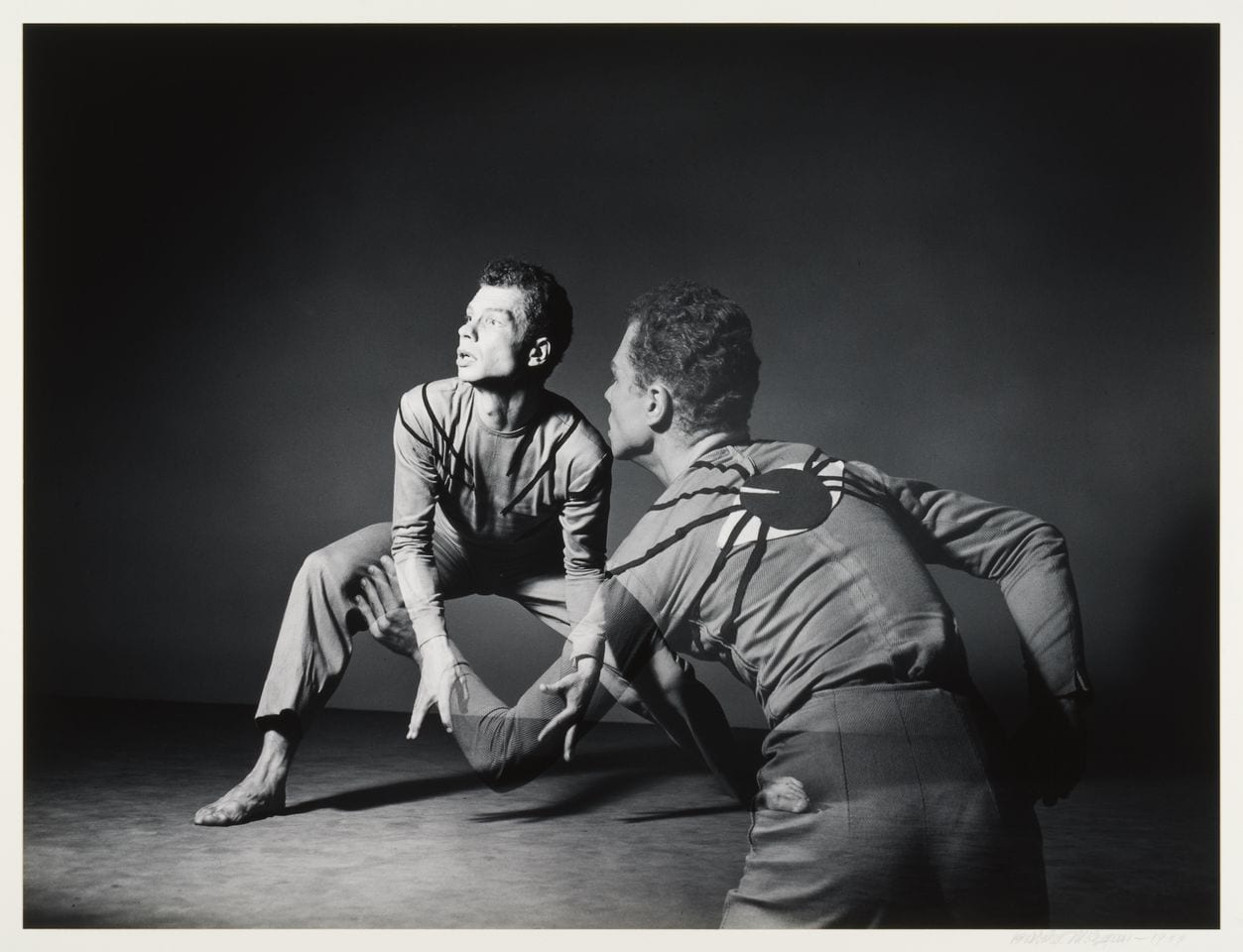

Barbara Morgan is known for her portrayals of the pioneers of modern dance. In a double-exposure, she captures Merce Cunningham crouching in positions that echo the image of a spider on the back of his costume.

Hung next to it is a quietly compelling portrait of the avant-garde composer John Cage by an unknown photographer, James Klotsky. Framed by the raised cover of a grand piano, Cage is lit from behind, which casts his face in shadow while reflections in his glasses obscure his eyes. It as though the portrait mirrors the difficulty audiences had in deciphering Cage’s music. Cunningham and Cage, long-term life partners and collaborators, appear here side-by-side.

Some of the photographers had close ties with their subjects. Imogen Cunningham warmly portrays her good friend and colleague Edward Weston, both leaders in the Modernist movement toward sharp-focus, tightly composed photography. Robert Richfield studied with photographer Aaron Siskind, who is known for his found abstractions, whether they feature fragments of graffiti on urban walls or patterns of lichen on stone walls in the wild. In Richfield’s portrait, Siskind stands in front of a stone wall, partially obscured by the rhythmic lines of slanting shadows cast by reeds that form a roof overhead. It’s as though he is portrayed within one of his own compositions.

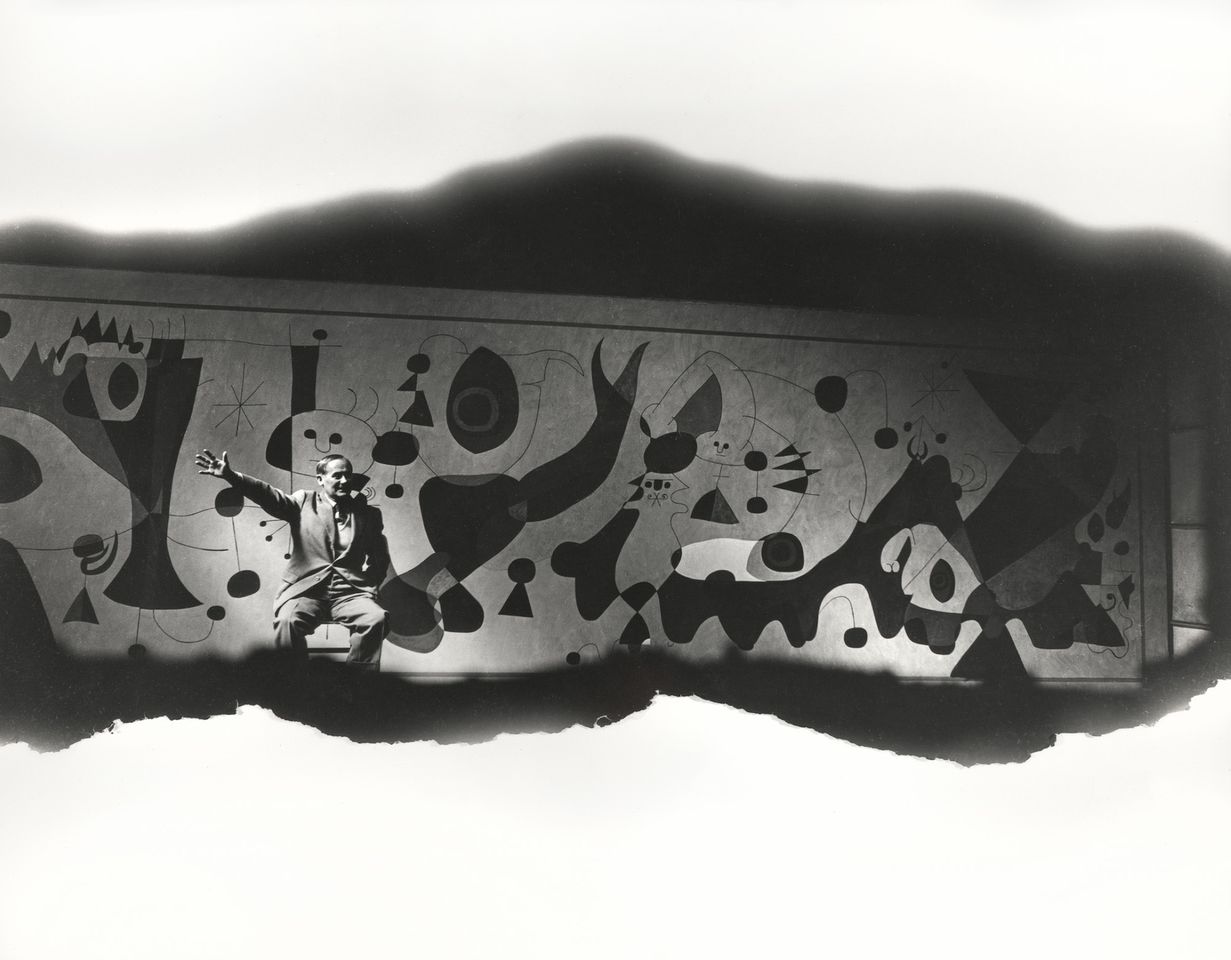

Perhaps the most unusual photograph in the show is Arnold Newman’s portrait of the Spanish painter Joan Miró in front of a wonderful mural that now belongs to the museum, and is mounted on the first floor, opposite the Terrace Café. Newman photographed Miró with the mural in New York, where a film crew documenting Miró’s first work made in America had poked a hole in a studio wall to accommodate the movie camera lens. Newman also chose to shoot through the resulting hole, but pulled back to allowing the irregular edges of the wallboard to frame the scene. He then tore the bottom edge of the photograph, creating an uneven edge that mirrors the irregular shape of the wallboard. It is wonderful to see the black-and-white photograph of the artist gesturing in front of his whimsical composition, and then visit the real deal—wall-sized and painted in vibrant color—downstairs.

Portraits of the Artist continues through June 22 at the Cincinnati Art Museum. For more information, visit http://www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org/.

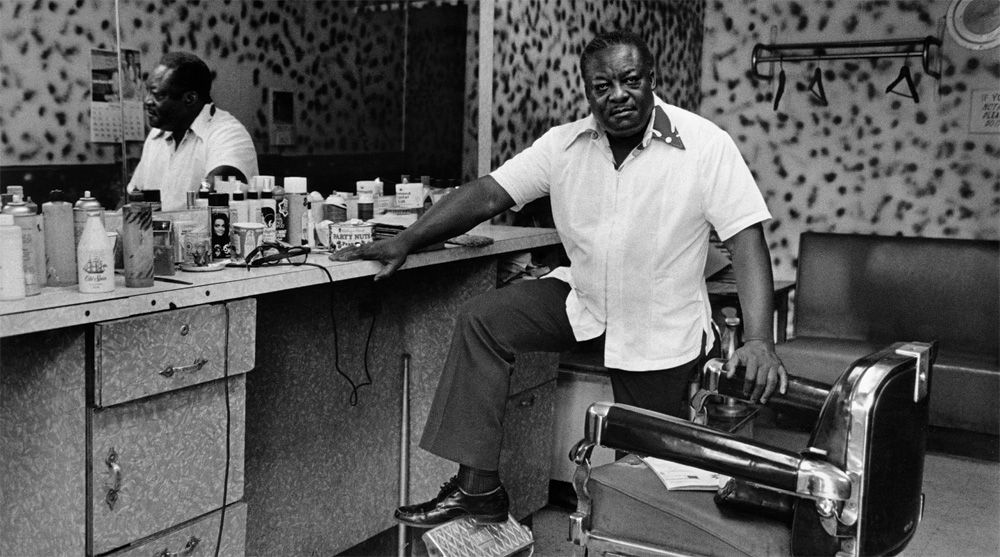

Sholis’s new project, Big Pictures, has just opened and continues for a year. Part of an effort to take art to the public, it will feature the work of two photographers featured on four billboards at a time. Over the year, a total of eighteen artists will be featured on thirty-six billboards. First up: photographers Dawoud Bey and Hannah Whitaker, whose work will be shown through July 14. For information and billboard locations, visit www.bigpicturescincy.org/.

Janie Welker is curator of collections and exhibitions at the University of Kentucky Art Museum