Gordon W. Bailey has given thirty-five works of art to the Speed Art Museum. A World in My View: Gifts from Gordon W. Bailey includes art by twenty-one artists.

An introductory selection of twenty-six pieces is on view at the Speed until February 5th. All of the artists are African-American and are predominantly from the rural south. The selection is extraordinary on many counts – for the authenticity and depth of emotion in many works, for the range and brilliance of invention, for the improvisatory response to a welter of non-traditional scavenged materials, and not least, for the boldness and freshness of color.

Testimony to religious faith is a recurring theme. Herbert Singleton’s Danieal in the Lion’s Den depicts a stalwart Daniel with a shepherd’s crook standing very upright, looking straight ahead, seemingly unfazed by the lion and lioness confronting him. A hole in the red painted board which provides the support for this sculpture in low relief reinforces the witness to faith: conviction outweighs correct spelling or traditional artistic finish. A jagged broken edge of the board is echoed in the lion’s bared fangs.

Nellie Mae Rowe is represented by Peace with Blue Hand. Rowe frequently traced her own hand in her art as a way of bearing witness and asserting her presence in the world. The hand points to the word “peace” and a bicolored red sun with green and brown rays. The curve formed by the artist’s thumb and wrist provides a contour for the silhouette of a bird: Rowe was a master at using one line to serve divergent forms. The hand/bird is flanked on the right by the back of a mauve cow and on the left by a pink-leaved flower crowned with a bud in the form of turbaned blue woman’s head. In Rowe’s art blue was often code for black. Race, mysticism, prayer, free association and a profound identification with nature come together in Rowe’s vision.

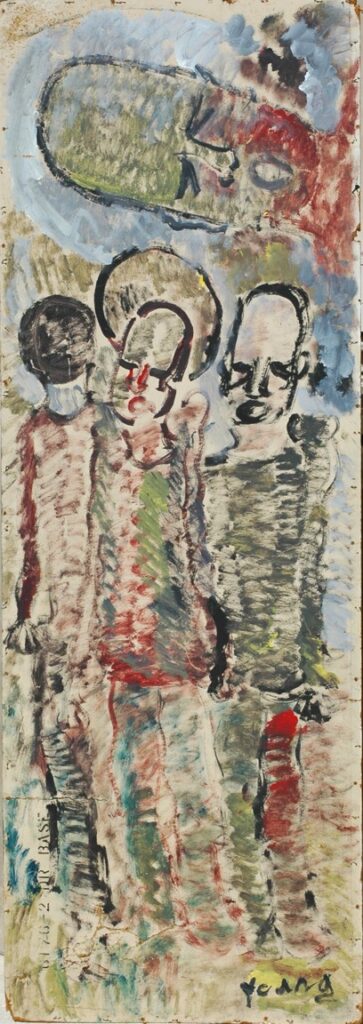

Purvis Young’s Christ Watching over Dudes shows the divine head loped over diagonally above three figures who are defined by an open weave of shimmering horizontal and diagonal strokes in green, carmine, black, blue and yellow. Christ’s eyes are closed and his mouth is open, as if in prayer. The three “dudes” are afloat, spectral presences, perhaps already entered into a redemptive afterlife.

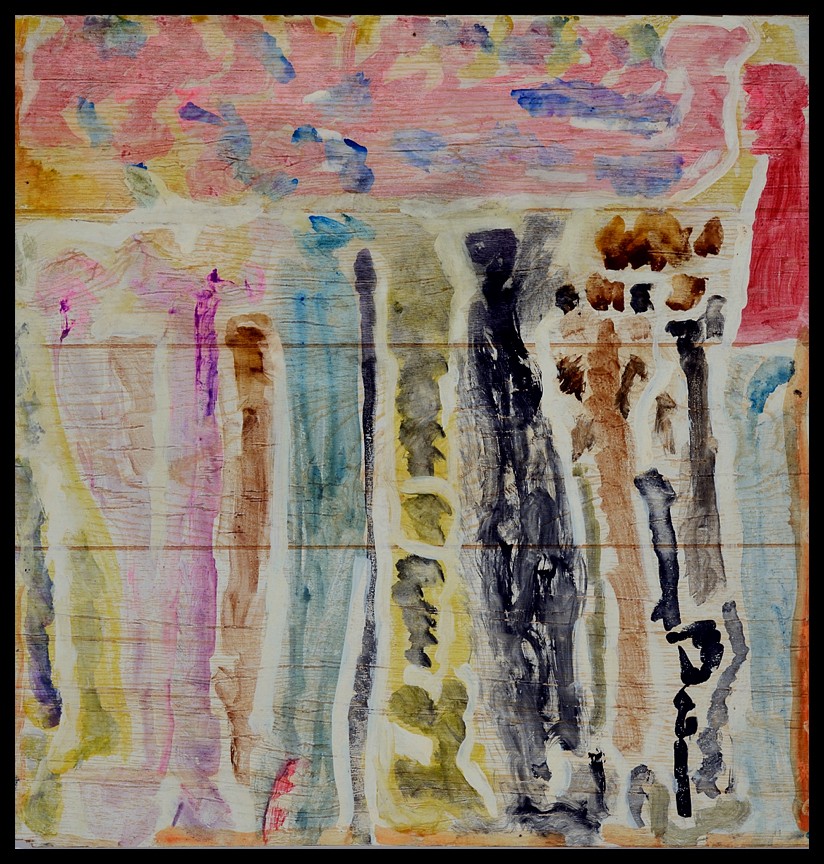

J.B. Murry’s work extends the spiritual theme. Murry was convinced that he was scribe for a divinely inspired “language of the holy spirit.” The example at the Speed holds its own as a color abstraction of the highest order: translucent horizontal and vertical squiggles form a rose, blue and yellow bar hovering over vertical trails of green, yellow, black, blue and purple, partially surrounded by an orange border. The indeterminacy and richness of markings are seemingly offhand but deft in their intuitive sense of economy, providing just enough for a work of art so inbred with transcendence that Murry’s belief that he was amanuensis to divine dictation has its own fictive plausibility.

Not all of the exhibition sticks to spiritual themes:Â Henry Spiller’s exuberantly bawdy women display their most intimate attractions with bravado, and Spiller’s extraordinarily well endowed donkey is depicted with echoing curves to provide maximum emphasis to this equine’s outsized masculine attributes.

Jimmy Lee Sudduth and Son House offer disorienting, unsettling experiences with their portraits of women. The body of Sudduth’s woman is defined by a brown circle seen against a yellow ground. The asymmetrical face addresses the viewer with a commanding, arresting stare. Comparably, Son House’s unfired clay head sports a wig, gold eyes and gold teeth, and her head is tilted to one side as if in animated conversation. In both works there is an uncanny sense of the unfamiliar familiar, artworks that seem very real without the traditional trappings of realism.

Equally haunting are Welmon Sharlhorne’s precisely delineated fanciful architecture, evoking funhouse or carnival buildings. Drawn on what appears to be the backs of yellow manila envelopes, the artist’s studied designs take their coordinates from folds in the paper. One of his drawings features a clown figure wearing a beanie with a clock on his nose. (Sharlhorne spent many years incarcerated and clocks and closed doors in his drawings may have autobiographical significance). The beanie demarcates the roofline of the building and flips in and out of three dimensionality, becoming a dome in Sharlhorne’s Escheresque perspective.

New York Times critic Roberta Smith has remarked that looking at the work of self-taught artists has made her “more open, less tolerant of rules and orthodoxies, more understanding of the human urgency to make art and how widespread it is.” The indigenous artists’ works on view at the Speed offer precisely that aesthetic liberation.