On Friday, March 11, 2022, The Carnegie in Covington, Kentucky opened A Thought is a River, curated by John Knuth (Los Angeles, CA). On view through August 20, 2022, this group exhibition includes seven artists from the Greater Cincinnati and Louisville areas who are “materially connected by an actual river and loosely connected by metaphorical rivers.†Featured in the exhibition are artworks by Kiah Celeste, Matt Coors, Adrienne Dixon, Albertus Gorman, Chris Hammerlein, Dale Jackson, and Letitia Quesenberry.

In a brief talk at the opening reception, The Carnegie’s Exhibitions Director Matt Distel introduced the show and curator Knuth, explaining that the works presented in A Thought is a River create a meandering exhibition experience, where thoughts, materials, and imagery flow from artist to artist, work to work. A Thought is a River sprung into existence when Distel invited Knuth to have an exhibition of his own works (entitled The Reds, which runs concurrently with A Thought is a River at The Carnegie) and, in turn, Knuth was introduced to a group of artists by Distel. After a series of studio visits, Knuth selected works from the seven artists on view to make up the exhibition. According to Distel, the project is somewhat about regionality, but mostly about connecting artists.

Both Distel and Knuth view the exhibition as a deeply collaborative endeavor, with Knuth serving as curator and Distel performing as organizer/facilitator. The non-traditional approach to exhibition planning and design builds off of Distel’s experimental and generative ethos. The hope here is to foster deeper connections and a flow of work and ideas among artists of the Ohio River Valley region and Los Angeles, where Knuth is based. Addressing the question of curation for A Thought is a River, Knuth opines and explains, “How do you collect a group of artists and give the show an overarching theme if it’s a disparate group of objects? As a river flows, there’s the babbling brook, and I thought of the downstairs area as [a kind of] happy hour, where there’s a conversation between the artists, maybe it’s a little bit noisier. And then as you move up in the space, there’s the dedicated solo shows to each artist.â€

Invoking the metaphor of a rambling river, branching into streams of thought and connection, the exhibition opens in the cavernous Rotunda Gallery. This lower gallery houses work from all seven artists, enabling rhizomatic connections among distinct practices. Where an overt theme is absent, viewers are invited to create these connections for themselves. The lines of association between works can be teased out in a number of ways; there are bright, attention-grabbing colors in the works of Coors, Dixon, and Jackson; Hammerlein, Gorman, and Celeste’s works traffic in collecting and amassing; there are aesthetic connections between the works of Coors and Letitia Quesenberry through their exacting, formal, controlled artworks; poetic moments bubble to the surface through any number of vistas.

In searching for connections between these works and the open concept of the exhibition, visitors may find themselves creating associations between artworks and bodies of water. Celeste’s sculptural work in the downstairs gallery includes a sand filter – an industrial object intended for pool treatment. Dixon’s stacked wood arrangements contain flowing drips of brightly pigmented paint, imitating dripping water. Gorman’s collections of ducks and Styrofoam floats provide easier entry into the idea of a river. More slippery are the works of Coors and Quesenberry, which potentially reference game-flow and surface tension, respectively. The large-scale installation of Jackson’s work is like a flood – a veritable deluge of words and colors. Hammerlein’s overt connection to the theme may come from the material the artist employs, but the stronger connection may be more in line with tracing the progression of a thought, as his piece Birth of Athena (2021) depicts the Greek goddess springing forth from her father’s head, fully formed and powerful.

Moving to The Carnegie’s upstairs galleries presents an opportunity for what are essentially, as Knuth pointed out, solo shows couched within the larger group exhibition. In the East and West Stairwells, leading to the upstairs galleries, Dixon has installed LED light tubes fitted with colored gels. These installations of gradient lights could function as markers of dusk and dawn; their fan-like arrangements communicate motion while demarcating space. In his brief gallery talk at the opening reception, Knuth noted the provocative interplay between Dixon’s work and the venue’s interior, where contemporary LED light tubes meet the French Renaissance style architecture of The Carnegie, a former library building listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

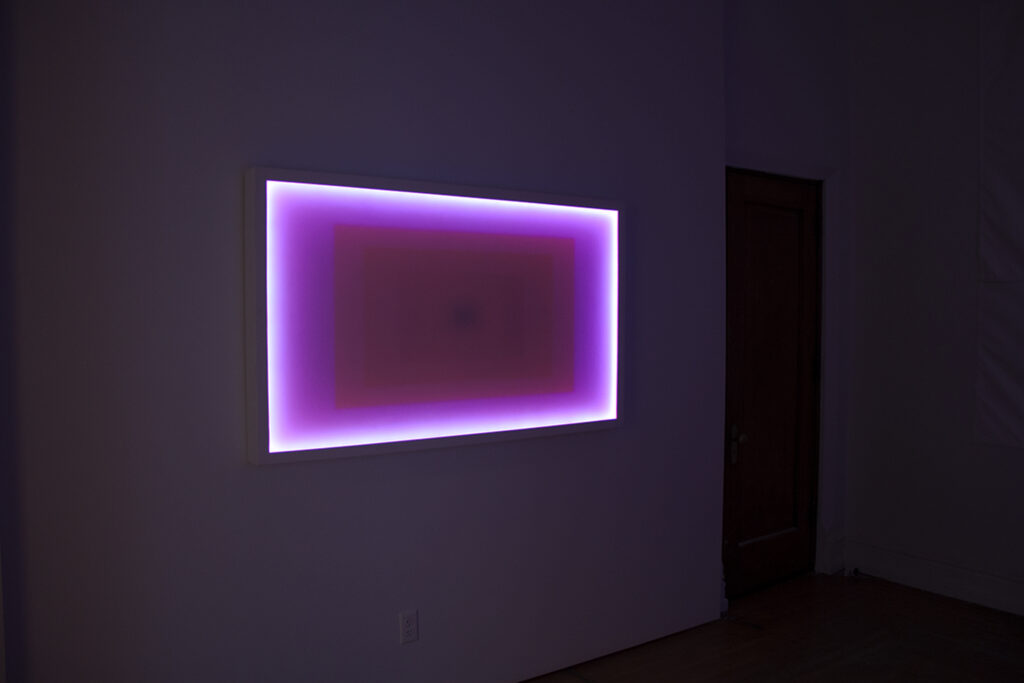

The Project Gallery houses three works by Quesenberry, each fabricated using wood, lacquer, LED lights, and acrylic. The gallery is darkened, allowing the shifting tones of LED light that emanate from the works to perform to greater effect. The works, entitled Hyperspace 37 (2020), Hyperspace 21 (2017), and Hyperspace 36 (2019), produce a meditative effect, drawing viewers into a lulling sense of movement. The works are evocative of James Turrell, and the emanating LED light creates a connection with the Dan Flavin flavor of Dixon’s works in the East and West Stairwells. One vista across the open space of the upstairs rotunda creates a sensual glow that draws the viewer in with ambiance, the softly shifting tones of Quesenberry’s works and gradient tones of Dixon’s inviting immersion while also signaling movement and transformation.

In the Semmens Gallery, visitors are presented with five text-based works by Jackson, a Visionaries + Voices (Cincinnati, OH) artist who creates stream-of-consciousness style poems and written observations on brightly colored poster board. The pieces upstairs offer an opportunity to be more intimate with the work, as opposed to the large-scale installation of Jackson’s untitled works that fill an entire wall in the Rotunda Gallery downstairs. The pieces are performative in an interior way, where the viewer’s action of parsing through the stories and complex poetry builds action within the mind and soul. The stream-of-consciousness style employed by Jackson in his everyday observations and associations evokes another kind of stream, creating a direct connection with the title of the exhibition with a sense of whimsy that is simultaneously banal and spectacular.

Five ceramic works by Hammerlein occupy The Carnegie’s Hutson Gallery. There is a starkness to the exhibition design within this pared-down solo show; there is no artwork on the walls. The gallery is populated by two raw-wood plinths on sawhorses topped with Hammerlein’s unglazed terra cotta works. The arrangement serves to push the viewer into an earthen space reminiscent of muddy river banks. The works themselves reference/illustrate several Greek myths. Compositionally, each holds a frantic energy in sexually charged tableaus. These works present opportunities to experience seemingly antagonistic forces within a singular body. They are raucous, yet still; they depict power while existing in fragility. The internal rhythms of individual pieces bleed into a larger conversation between the works and within the exhibition space to produce an unsettling feeling that one doesn’t quite want to abandon without deeper investigation.

In the Duveneck Gallery, the works of Coors and Celeste create a strong opportunity to suss out connections and divergences. Celeste occupies one-half of the gallery with muted tones in her found-object sculptures and black and white photos of her body-as-sculpture. Coors’ work contrasts with Celeste’s with vibrant, saturated hues in panel works and textile sculptures. Where Celeste evokes the industrial, Coors taps into the domestic. Between the two artists, an incredible sense of rhythm is built, both within the works and installation strategy. The repetition of forms and materials contributes greatly to this effect. In Coors’ works, we see the repeated pattern of a chessboard borne out in five works, punctuated with photographic imagery. In his four other works, made of fabric, Coors brings forth undulating and cascading compositions. These works are balanced at the other end of the gallery space by Celeste’s two sculptures, which channel movement and rhythm through the use of reclaimed vacuum hoses. The black and white photos documenting Contingent Sculptures (2021), liminal offerings somewhere between performance and sculpture where Celeste documents her own form as the body of the sculpture, underscore the sense of movement built into this particular gallery’s installation design.

The architecture of The Carnegie and the layout of the exhibition does indeed push the viewer’s body to meander through the space, stopping here and there to wade in deeper into the individual galleries. And again, the body is urged to circle and swirl within the individual galleries to gain a deeper sense of what is happening in the works, and how they connect to each other within the larger exhibition. Save for the exhibition statement installed in vinyl lettering near the bar in the Rotunda Gallery, there are no statements or panels or title cards throughout the show. Instead, QR codes with a link to the exhibition checklist are posted at the entry of each room. While this move works to cut down on visual clutter and keep the focus on the artworks on view, it also removes statements about individual works, and thus removes additional access points for audiences to enter the conversation through. However, it is a move that urges, and even requires, that viewers investigate each piece individually to determine how and why everything fits together and, in that sense, helps to drive home the participatory, performative, and engaging curatorial aspects Knuth has built into A Thought is a River.

A Thought is a River is on view at The Carnegie in Covington, KY from March 11 through August 20, 2022. Top image: An installation view of A Thought is a River, curated by John Knuth. Works by Matt Coors and Dale Jackson are on display in The Carnegie’s Rotunda Gallery (left to right). A painting hangs on a wall to the left, and the piece on the right covers the entire wall in a pink, yellow, green, orange, and white grid. There is writing in each square. Photo by CM Turner.