The coal mine, itself a central character in Emile Zola’s late nineteenth-century novel, Germinal, is described as “evil-looking, a hungry beast crouched and ready to devour the world.â€Â When one of the miners spits out a black blob, another asks him if it’s blood. He declares, “It’s coal. I’ve got enough in my guts to heat me till the day I die. I guess I stored it up without even knowing about it. Well, it keeps your insides from spoiling.â€

A recent exhibit at the Lexington Public Library, East Meets West, bestows this kind of dubitably dignified human face on coal which seems to exemplify the pride miners take in making an honest living, and the role they play in supplying their nation with energy and power. Paradoxically, though, black dust mingles with their blood and flows through their veins much like the seams of coal that run between the overlying and underlying strata of rock within the mine.

The two Chinese artists who created these works have a particular interest in this subject matter. Xiaoan Li is the Dean of the College of Fine Art at Shaanxi Normal University in China, and Dongfeng Li is an Associate Professor in the College of Arts and Design at Morehead State University. Although they share the same last name and a similar vision, they are not related. So to avoid confusion, I will refer to them by their first names.

In 2010, Dongfeng was awarded a four-year grant from MSU to compare coal mining methods and practices between China and the US. He selected two mines in Martin County, Kentucky (Inez) for his study and formed a collaboration with Xiaoan, whose university is located in Province of Shaanxi, the largest coal mining district in China. His initiative was to address the differences in mining facilities, working conditions, safety standards, rates of pay, benefits, and more important, the human factor, which the two men have dutifully and creatively expressed through their art.

Xiaoan is on leave from Normal University this semester to work with Dongfeng at MSU where their collaborative efforts culminated in this important body of work. They spent many hours visiting and talking with miners (and their families) employed at two separate mines in Inez. It is from these repeated encounters and numerous sketches that they gained the soulful perspectives reflected in their paintings. Equally important, both artists’ medium and style are representative of the culture in which each is deeply rooted, the East and the West.

Dongfeng paints with watercolor (and occasionally pastels) on watercolor paper and yupo paper, a tree-free, synthetic, multimedia, recyclable paper that is gaining greater appeal with Western artists and graphic designers. Xiaoan, on the other hand, paints with brush ink on rice paper, more common to the Eastern tradition of artistic expression. In both instances, however, the message is powerfully embedded in their respective mediums.

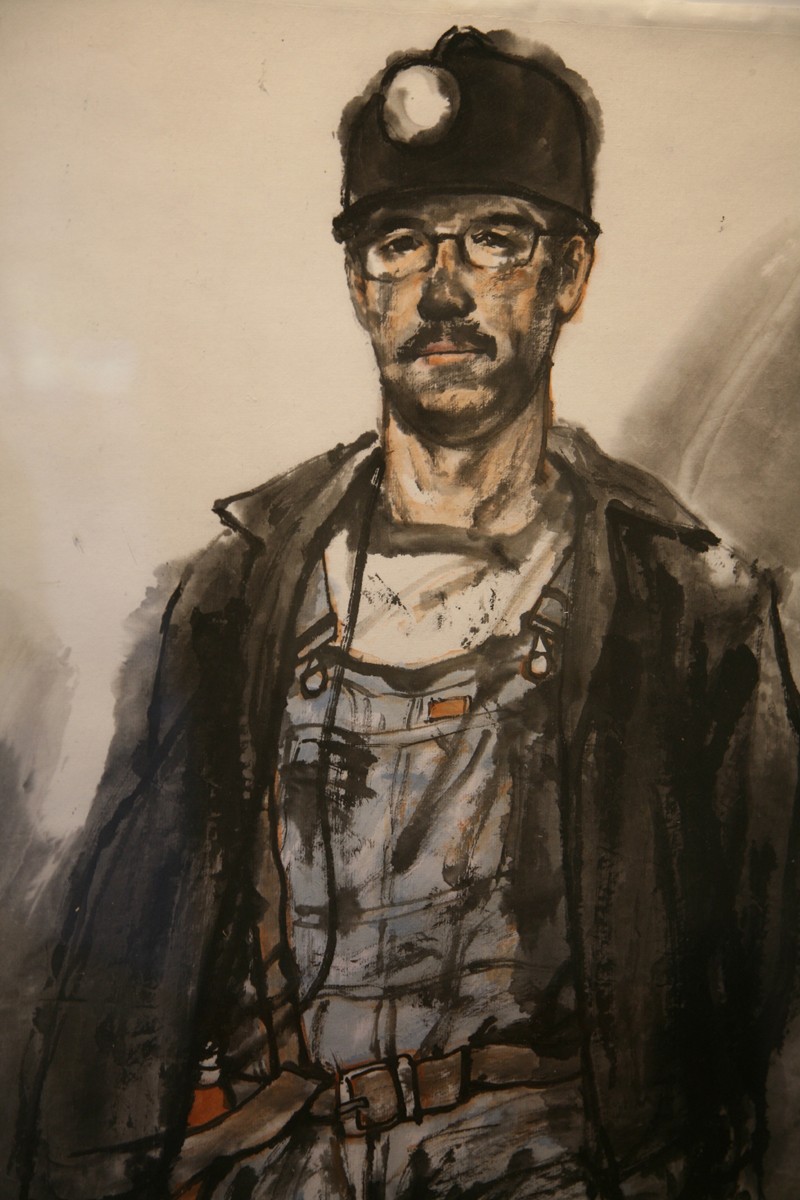

In Dongfeng’s “Coalminer,†the transparency of the watercolors seem to make the spirit of the inner man transparent as well. The miner is reticent and pensive as he stares almost blankly into the space before him. He looks sad and lonely, yet determined. He knows his headlamp with its battery strapped at his waist will light his way into the darkness and out again after a long day (or night) of hard labor.Â

The gloomy and muted monochromatic shadows in the background of this painting are juxtaposed by the sharp contrast of lighter tones on the figure itself and appear to offer some sort of salvation. Although we see a face filled with resignation, it also radiates kindness and hope, apparent mostly in the eyes which are said to be the window to the soul. It would not have been possible for the artist to evoke this kind of empathy without understanding his subject and the hardships involved in living the life of a coal miner.

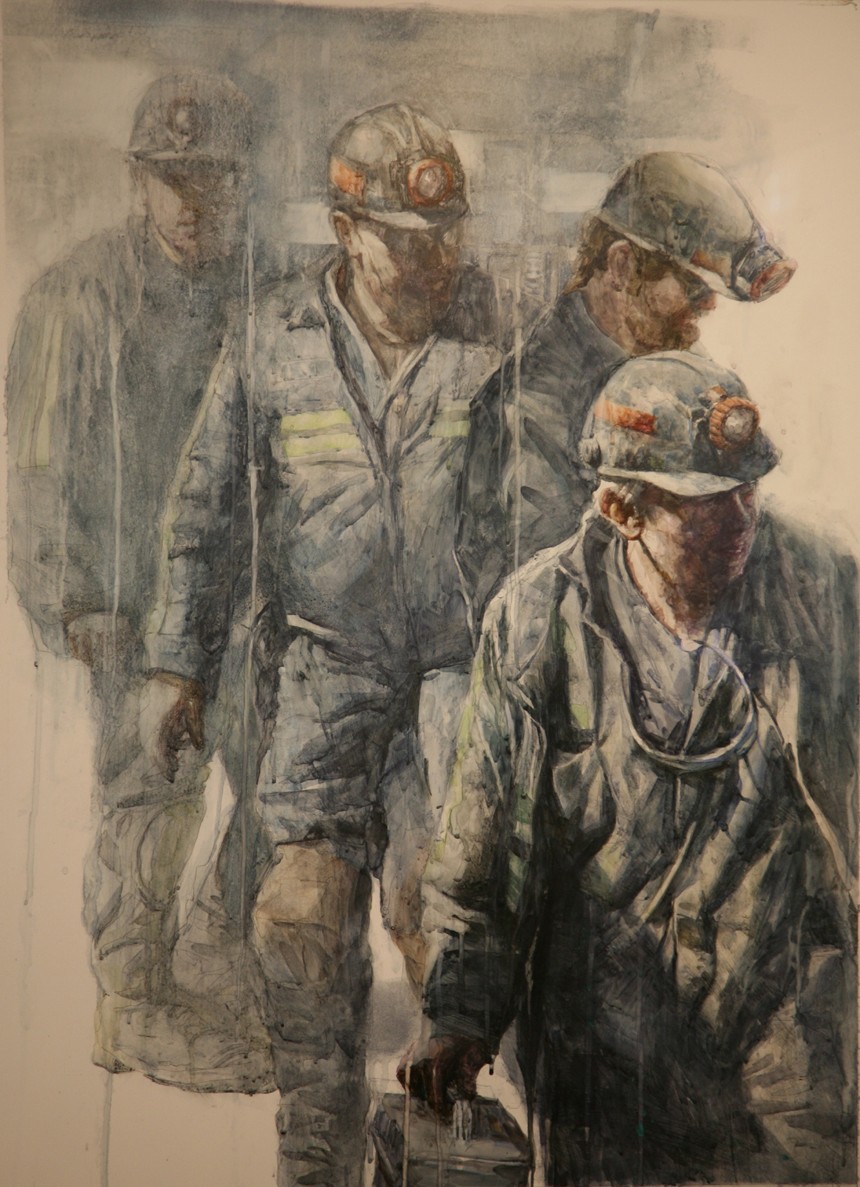

Dongfeng’s “Deep Down Under†has a Duchamp-like feel as if this is the repeated movement of a single figure descending into the pit of the mine. Unquestionably, there are four miners here, but as the eye moves from the clearly-focused miner in the foreground to the fourth miner in the background, that individual takes on the appearance of an apparition or a ghost. The painting simultaneously projects a heavy, yet ethereal air as the artist deftly employs space and varying hues of color to create a sense of depth, both literally and figuratively.              Â

The orange strips on the miner’s hard hats remind me of a sticker that my father (who was a mine superintendent) wore on his hat which said, “Be careful buddy.â€Â He had all his men wear them as well, cautioning them to be ever vigilant of the dangers that lurked inside the mine. Also, the protective eyewear calls to mind another slogan that was worn on the other side of their hats, “Safety first.â€

I can almost smell the coal dust on this miner’s face and clothes in Xiaoan’s “Kentucky Coalminer VII.†It is a portrait of another type of black pride, that honest day’s work I mentioned earlier. This brush ink on rice paper captures the very essence of the coal miner. Cezanne would have called it “coalminerness.â€Â          Â

Realistic, representational, and symbolic, Xiaoan’s rendering is stark and simple. The ink brush strokes are definitive and opaque, portraying this miner as a staunch loyalist, a company man, someone totally committed to his work without fear or trepidation. The bold lines that define his figure, the partially blackened face, the loose-fitting clothing, and the twisted belt outlines a man whose clothes may not exactly fit him, but he fits the job. And as a fellow coal miner, he’s got your back, and you can trust his courage and resolve.

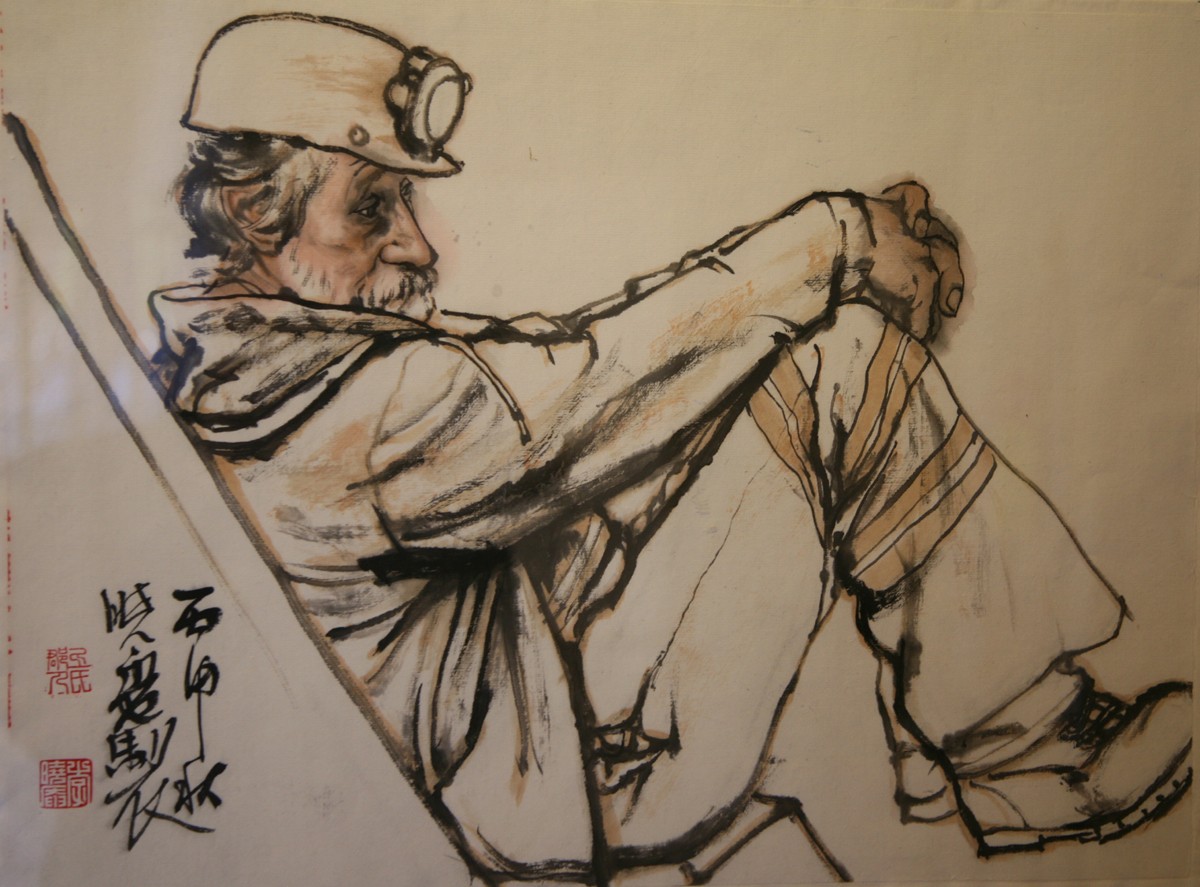

However, Xiaoan’s “Kentucky Coalminer VIII†presents a slightly different take, one of weariness and fatigue. This older miner is either taking a break or is on a mantrip, the coal cars that take the miners into the hillside at the beginning of the work day and brings them back out when the day is done. This is the only horizontal piece in the coal mining series, and it speaks of a desire for repose not yet to be found. The thin brushstrokes delineating the form in a seated position and the flesh tones ascribed to the miner’s face and clutched hands help humanize and emphasize the quandary he seems to be experiencing that is his life. Again, without the artist’s insight into the travails of coal mining, a message such as this could not be so effectively and artistically communicated.Â

The coal mining industry can never be glorified. It is the usurper of the workers’ bodies and souls. For most of us, the life cycle is from the cradle to the grave. Growing up in the Eastern Kentucky coalfields, I came to understand that it was from the mine to the grave, and in many instances, the mine became the grave. Too many times after a rockfall from a poorly supported roof, miners died. Too many times after a methane or rock dust explosion that ripped through the tunnels, miners died. Too many times rescuers could not safely retrieve the charred and crushed bodies from these disasters, so they were sealed up inside the mine. It became their tomb, their eternal resting place with roof rock for a headstone.Â

Well over a hundred years ago, Zola’s personification of the coal mine as a “hungry beast crouched and ready to devour the world†was prophetic. Today’s climate change and global warming, not to mention mountaintop removal, bears this out. And his character who proclaimed that coal “keeps your insides from spoiling†was kidding himself. I watched my father die of black lung disease. He was only 62.Â

There were 33 pieces in this exhibit, and the subject of coal mining comprised about half of the show. This stands to reason since the project evolved as a result of a major grant, and from Professors Li and Li’s strong collaboration to produce an invaluable statement about coal mining in Eastern Kentucky. At the same time, they are endeavoring to make Morehead State University and Shaanxi Normal University sister schools by establishing a student-exchange program. So there is light at the end of the mine tunnel, and it’s not an on-coming coal tram or an explosion. It’s enlightenment.

The remaining works of both artists are high-spirited, soothing, and optimistic. To see what I mean, take a good look and Xiaoan’s paintings of Thanksgiving, a squirrel, an orchestra conductor, a reader, or one called “Triple Happiness.â€Â Likewise, Dongfeng’s “Pikeville’s Tranquility,†“Healing Rain,†and “Augusta Ferry†provide a respite from the intensity of the subject of coal. All of these paintings are matted, or deckled, and framed.

Photos were taken and used with permission of the artists.