Every art form is a refuge and a prison. Many artists spend much of their careers working in the spacious house of a particular medium or genre, only to discover, sooner or later, that it seems to have shrunk, sometimes intolerably. Some respond to this creeping claustrophobia by moving to a new house, or burning down the old one and starting fresh. Picasso did this more than once. So did Mondrian, whose early and late works seem to have been painted by two different people, and the nomadic Philip Guston, who moved from figurative work to abstraction and back again. Other artists add additional rooms to their original homes, perhaps a new wing, building out from the old foundation.

In Brilliant Illusions: Crafted Forms by Li Hongwei and Todd Hido: The Poetry of Darkness at the University of Kentucky Art Museum, we encounter two artists in the latter group. Li, a Chinese artist who divides his time between Beijing and New York, and Hido, an American artist who grew up in Ohio and now lives in San Francisco, are both engaged in expanding, transforming, and to some degree transcending older art forms: traditional Chinese ceramics in Li’s case, photography in Hido’s. Viewing these exhibits, which continue through June 4, you feel the artists’ reverence and restlessness, their respect for the old and their hunger for the new. Neither is an arsonist, but neither is content to stay within the original floor plan, opting instead to knock out walls or dig tunnels to the house next door.

Li’s renovation is more extensive and more radical, in part because of the sheer weight of the history he’s alternately cleaving to and departing from. Is there anything more beautiful, more lasting, more perfect in its way than the body of work created by the great ceramicists from the Song (960-1279 A.D.), Ming (1368-1644), and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties of China? The fact that this is a legitimately arguable question says everything about how heavy the burden of legacy can be for someone working in an ancient tradition and intent on making his own statement.

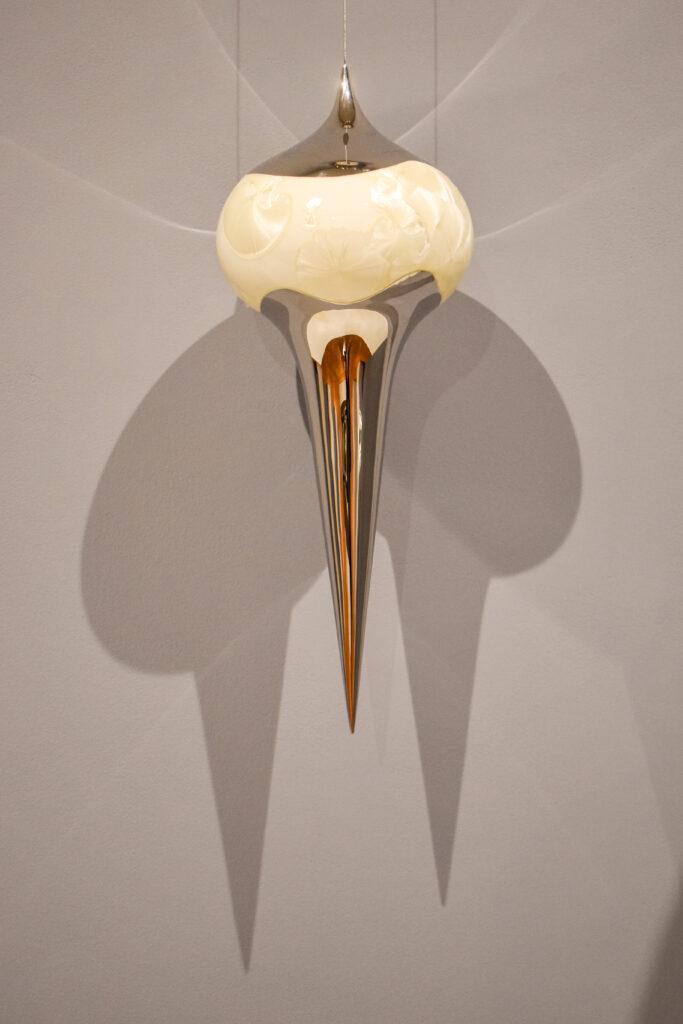

In “Brilliant Illusions,†Li starts with the oldest and most elegant of ancient forms, the vase, and then spins it forward a full millennium into the realm of 21st Century conceptual art. His simplest pieces here are porcelain vases in classical shapes evoking pears, olives, and garlic heads, swathed in richly ornamented, traced-ink splash glazes suggestive of flowers, ginkgo leaves, perhaps clouds, perhaps sea creatures. They’re old-school stunners, but they feel like warm-up acts, not main events. Elsewhere, by warping his shapes in unexpected ways and supplementing his crystalline glazes with patches of highly polished stainless steel – in whose curving mirrored surfaces viewers can’t help seeing themselves – Li turns the act of looking at his work back at the looker. In his “Xuan†series featuring bulbous shapes that suggest raindrops falling upward rather than downward, viewers are always looking not only at the object itself but also at their own images, stretched vertically (and sometimes horizontally) as if in a funhouse mirror. (Jeff Koons sidled in this direction with several of his shiny porcelain and metallic sculptures from a quarter-century ago, and Anish Kapoor put a giant, bean-shaped bow on the trend with “Cloud Gate†[2006], his crowd-pleasing public sculpture in Chicago.) The illusion of upending the laws of physics continues in Li’s “Upwelling of Gravity†series, in which porcelain and stainless-steel masses emerge from slender bases upward into a flaring, bulbous top reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s counterintuitively up-tapering columns in his Johnson Wax Building in Wisconsin (1939). Wright’s delight in gravity-defying cantilevered masses, at Fallingwater (1935) and elsewhere, might also be a guiding spirit in Li’s virtuosic “Allegory of Balance #18,†in which several variously clad shapes are joined and precariously stacked on (or suspended from) one another.

Li’s three primary impulses – to remake the old into something new, to beguile viewers into seeing the world in a different way, and to interact with us by providing reflections of ourselves in the act of consuming art – come together in his “Illusions†series. In these pieces, traditional glazed porcelain vases seem to have been cut in half vertically and attached, upside down, to a mirrored surface. If you stand a bit to one side below eye level, the missing half of the base’s neck seems to be there in the reflection, restoring the vase to an illusory completeness – a metaphor, perhaps, for the ability of art to make fractured things whole. And if you stand directly in front of these pieces, you can’t help seeing yourself getting in on the act. Are you, in this case, part of what’s been fractured and, maybe, made whole? It’s a question you have to answer for yourself.

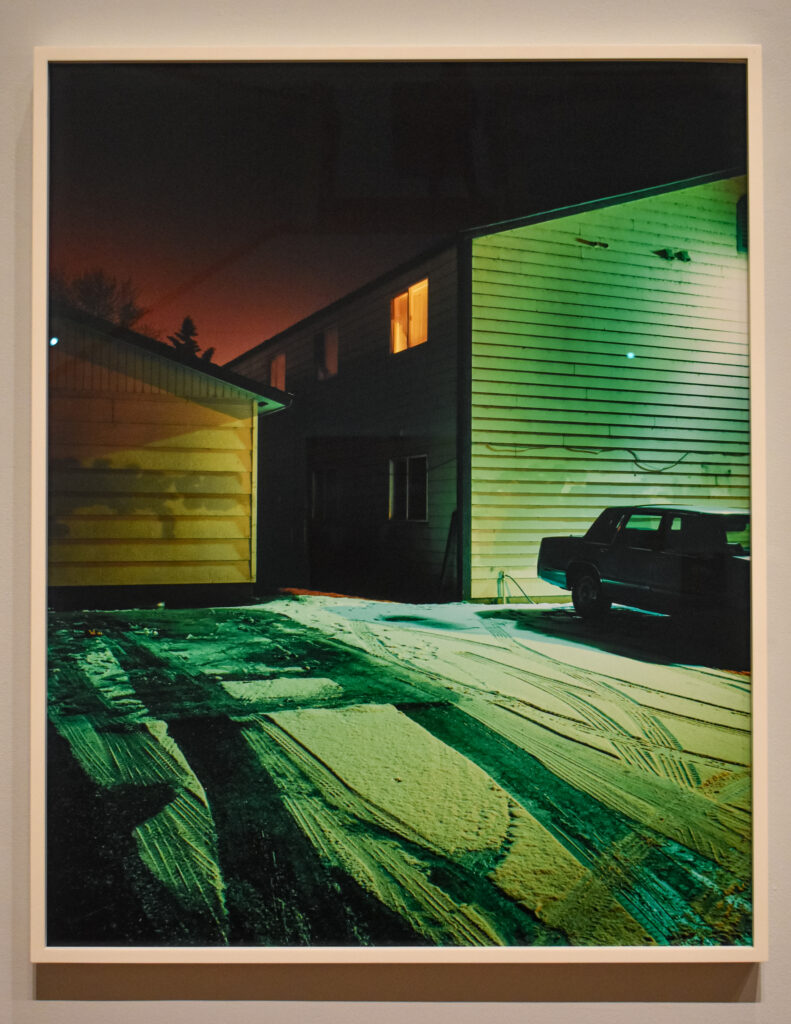

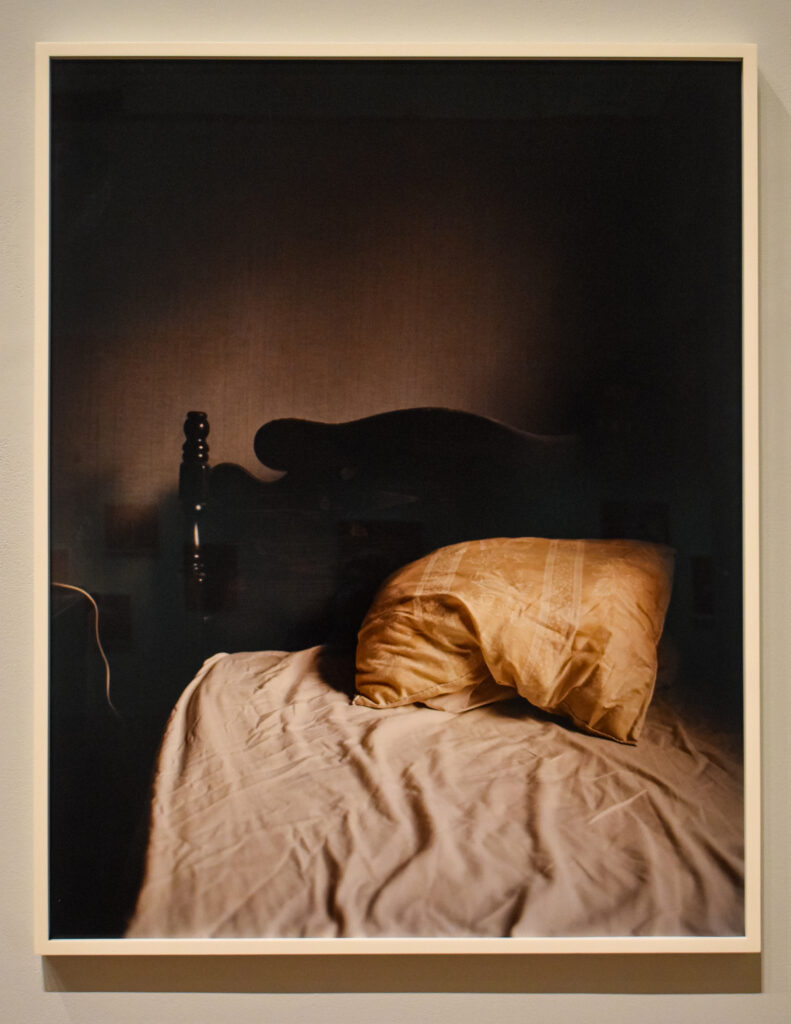

In “The Poetry of Darkness†(which takes up most of the museum’s main gallery downstairs), Hido seems to be pushing photography in the direction of literature, painting, and finally cinema. His moody, desolate, sometimes vaguely lurid pictures of lonely houses and other buildings with lights burning at night – most from his “Homes at Night†series, including several collected in his book House Hunting (2019) – accompany haunted rural landscapes and closeups of women apparently in distress often feel like scenes from film noir, horror movies, and/or fantasy epics. His crepuscular images of vacant fields and country roads fairly thrum with foreboding, melancholy, and menace. The way the mostly untitled prints are displayed in the gallery here, in groups of two, three, and four, reinforces these loose, often unsettling narratives. In one grouping, for example, two eerie images from the “Homes at Night†series – including an old motel photographed through what might be the windshield of a car – are paired with a tight shot of a woman recoiling in horror. We’re left to imagine what she’s reacting to, but the juxtaposition of the photographs suggests it’s something happening in one of those buildings. Brrr.

Hido has said that he shoots photographs like a documentarian and prints them like a painter – which involves, presumably, manipulating and overlaying the original exposures with visual effects that result in darker lighting and shadows, richer colors, and softer focus. Often the pictures feel suffused with sinister enchantment of the sort I associate with Gothic fiction of the 19th century, as if just around every corner we might stumble on a castle that belongs to Dr. Frankenstein, Count Dracula, or Roderick Usher – except that the place and time are clearly, ominously, our own. The curse that casts a pall on these brooding scenes has more to do with the threat of foreclosure, climate change, our increasingly toxic political culture in America and the world beyond, and the attendant anxiety and depression that often comes with all these factors.Â

Hido is a protégé of the late, great photographer Larry Sultan (1946-2009), whose subtle, quietly heartbreaking photographs of his aging parents, collected in his book Pictures from Home (1992), constitute a high-water mark in visual storytelling. The student has learned much from the master, but he has other masters, too. Hido has said that his influences and touchstones include Alfred Hitchcock, perhaps our greatest poet of darkness. The stories Hido tells – about the lives of people barely hanging on in the suburbs and large stretches of the American heartland – are mostly implied, though no less potent, and would be right at home in the settings imagined in films like Shadow of a Doubt, Psycho, or The Birds. It wouldn’t surprise me to hear that Hido has dug himself a tunnel to the world of full-time filmmaking someday. He’s halfway there.

Brilliant Illusions: Crafted Forms by Li Hongwei and Todd Hido: The Poetry of Darkness is on display at the University of Kentucky Art Museum January 21 – June 4, 2022.

Top image: Li Hongwei, Brilliant Illusions: Crafted Forms, installation view. Several organic-shaped sculptures are on display on pedestals and hanging against a gray wall. Photo by Kevin Nance.