The “Picturing Motherhood Now” exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art is far from a warm fuzzy Hallmark card to motherhood. It is an exhibition that explores all the complexities of motherhood, including feminism, sexism, and racism. The work is created by a group of 33 diverse artists, including many young minority women who are all too often overlooked.

You are greeted with a painting by Mequitta Ahuja, but I am quickly drawn to the sculpture MMDP (Verbal Magic) 2016 by Kaari Upson. This is by no means a reflection on the work by Ahuja; I am merely trying to understand the connection of Pepsi and motherhood. Upon reading the artist’s statement, I learned of her mother’s love and ritual of popping the top of a Pepsi can daily at 4:00 PM, a habit which “repelled” Ms. Upson. The cans stacked repetitively down the wall, perhaps reflecting the repetition of her mother’s habit of drinking them.

The artist created the piece by pouring aluminum into the cans to amalgamate and burn off the colors from the inside, leaving them looking fossilized. Pepsi became a recurring theme throughout her work and reflected her turbulent relationship with her mother.

Mequitta Ahuja’s Portrait of Her Mother, 2020 connection to motherhood is more evident. A self-portrait of Mequitta holding a painting of her mother, their shared features are apparent as she paints in her studio. A layered self-portrait of cool blues and reds.

It is always a privilege to see the work of Carrie Mae Weems. The exhibition includes 20 platinum photographic prints and 14 letterpress text panels from her iconic The Kitchen Table Series created 30 years ago, marking the beginning of her prolific career. The photographs form a grid, as do the text panels, which are off to one side.

A series of quiet black and white photographs of a woman going through life under a solitarily overhead lamp at her kitchen table. Weems plays the lead character; she has said it is less about self-portraiture, more that she was a convenient stand-in actress/model. Every day for a year, she made a photograph, telling the story of a woman who goes through her days at a kitchen table and all the roles she plays. She is a mother, lover, daughter, friend, as well as alone, directly confronting us.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is one of only a handful of institutions that holds this Weems collection in its entirety.

It is not often we get to see the work of a mother and daughter in the same exhibition as is the case here with Betye Saar and her daughter Alison. Miss Betye, now 96, is still creating work; her daughter Alison was born in 1956.

The elder Saar has spoken often that art is her weapon: “My work started to become politicized after the death of Martin Luther King in 1968. The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, which I made in 1972, was the first piece that was politically explicit.â€

Aunt Jemima became a warrior in her work and no longer a symbol of servitude. In The Liberation 2014, she is on a washboard and is armed and dangerous, with a spoon in one hand and a gun in another. She is no longer a servant to the whims of white folks.

In what appears to be a quieter piece, Lest We Forget, The Strength of Tears, The Fragility of Smiles, The Fierceness of Love, 1998, Ms. Saar has taken her and assembled her in a small wooden box, a drawing on one side flowers and an old quilt on the insides. Here she is smiling, a grenade in hand as she stands on what appear to be dentures, a watch on her stomach, time is ticking.

Her daughter Alison’s work follows her mother’s tradition; black women no longer are victims of racism and servitude. Her sculptures are ready for action with weapons of yesterday’s work. Exhibited here are three from her series of five called Topsy; the name comes from Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

The sculptures were made with vintage found tools and materials such as wood, copper, ceiling tin, bronze, and tar. They stand at the ready in the middle of the exhibition; they cannot be ignored.

Aaron Gilbert’s oil painting Dinari/All Our Mothers, 2019 of a mother putting eye shadow on her daughter is a tender moment. Until you look a little closer, and the subtle struggles are revealed in the form of an ankle monitor and bruises on the mother’s leg, yet it doesn’t take away from the tenderness of this mother-daughter moment.

Gilbert’s painting hangs next to the self-portrait of photographer Catherine Opie breastfeeding her son Self-Portrait/Nursing, 2004. This piece seems a long way from her days of images with titles like Self-Portrait/Cutting and Self-Portrait/Pervert when her work was focused on her cutting and sadomasochism. The scars are still visible from this earlier work. A half-circle above her full nursing breasts reads “pervert”, which she had cut into her skin. Yet her images carry warmth even when dealing with subjects that might feel a bit taboo for some.

Louise Bourgeois (Spider IV) and her spiders have a corner of the exhibition space; she did not start creating her spider sculptures until the 1990’s when she was well into her eighties. The sculptures here are far from her largest pieces which have garnered significant praise, but they are prominent here and get your attention. Her drawings are included as well; spiders often represent her mother, perhaps because she was a weaver or maybe because there are often tangled webs between mother and child.

Andrea Chung is a young artist who focuses on the midwife, often an unsung hero of motherhood. Sage, Dandelion, and Marigold, 2020 is magical with disappearing images made from midwives’ clothing. This work is a complicated process that includes raspberry tea, embossed paper, and a lightbox. The disappearance of the images reflects her thoughts on the often lacking history of midwives.

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Kinships are photographs of three generations of women during the Flint, Michigan, water crisis. Her black and white photos are both documentation and a tribute to survival in the midst of crisis.

What you don’t see in Titus Kaphar’s Not My Burden is what’s important. His painting shows two black women in a colorful room, each holding young children, but the children are missing. The painting has been cut out, and we are left with harsh whiteness among the colorful surroundings of the rest of the painting. You can’t help but think of all the black women who historically lost time with their own children caring for those of others.

The exhibition added community voices and statements about motherhood, next to the artists’ statements. While I think it was a nice idea, I found them a bit distracting and felt they took away from the artwork. Perhaps if the placement was different, they might have been more successful.

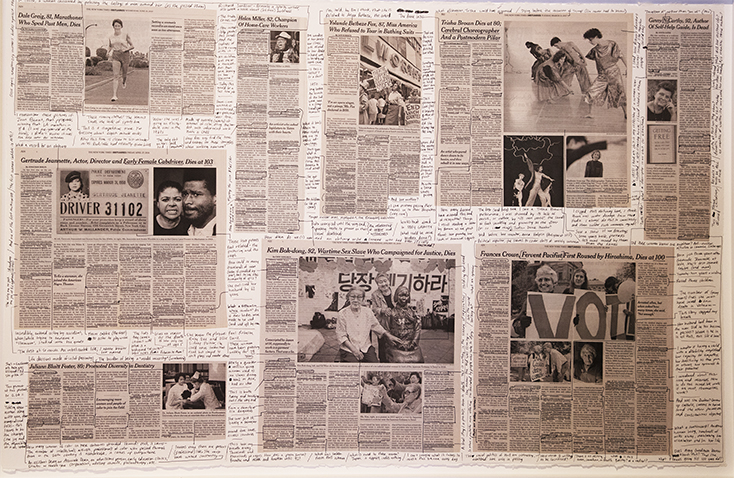

Appropriate towards the exhibition’s exit is a commissioned collage by Carmen Winant called Passing On, containing obituaries of feminists from The New York Times with her notes and thoughts included. As someone who always reads the obituaries, I often think about what I would like mine to say or how I want to be remembered. I have never given a lot of thought to someone’s views on me. Winant quotes her mother, “The generation who invented modern feminism and provoked social revolution is passing. How will we remember them?â€

This is a complex exhibition, just like motherhood itself.

“Picturing Motherhood Now” is on exhibit at the Cleveland Museum of Art through Sunday, March 13, 2022.

www.clevelandart.org/exhibitions/picturing-motherhood-now

Photography by Sarah Hoskins