Miami is one of those cities – like New York, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Lexington – with a unique mythology. It has a persona in the national consciousness, a polished surface it presents to the world: a tropical paradise of sandy beaches, manicured golf courses, sleek condominium towers, Art Deco hotels, and extremely attractive people rollerblading on sun-drenched promenades or sipping icy cocktails under the shade of lush palm trees. From the 1960s, when Jackie Gleason broadcast his variety show from the city, to the 1980s, when Don Johnson modeled a series of creamy linen suits and pastel shirts in “Miami Vice,†Miami solidified its image as a gleaming playground for the rich and glamorous.

Funny thing about that word glamorous. It doesn’t mean beautiful. It means a concerted attempt – by charm, by artifice, by the casting of spells – to bamboozle the viewer to see beauty where none exists.

“A More Fluid Atmosphere,†an Institute 193 exhibition of slyly evocative, eerily distant work by the Miami-based photographer Rose Marie Cromwell, offers glimpses of some of what’s just beneath the city’s shimmering surface. In the show – which ran through Dec. 18 and can be viewed by appointment through Dec. 28 – Cromwell takes us behind the main thoroughfares to the side streets and back alleys, the construction sites and the trash dumps. In these barren, off-the-beaten-path locations far from the sexier parts of town, we see whispered hints of what it takes to maintain the facade of perfection, along with the byproducts and the environmental and human costs of that effort in a multi-ethnic, socioeconomically stratified, rapidly gentrifying city.

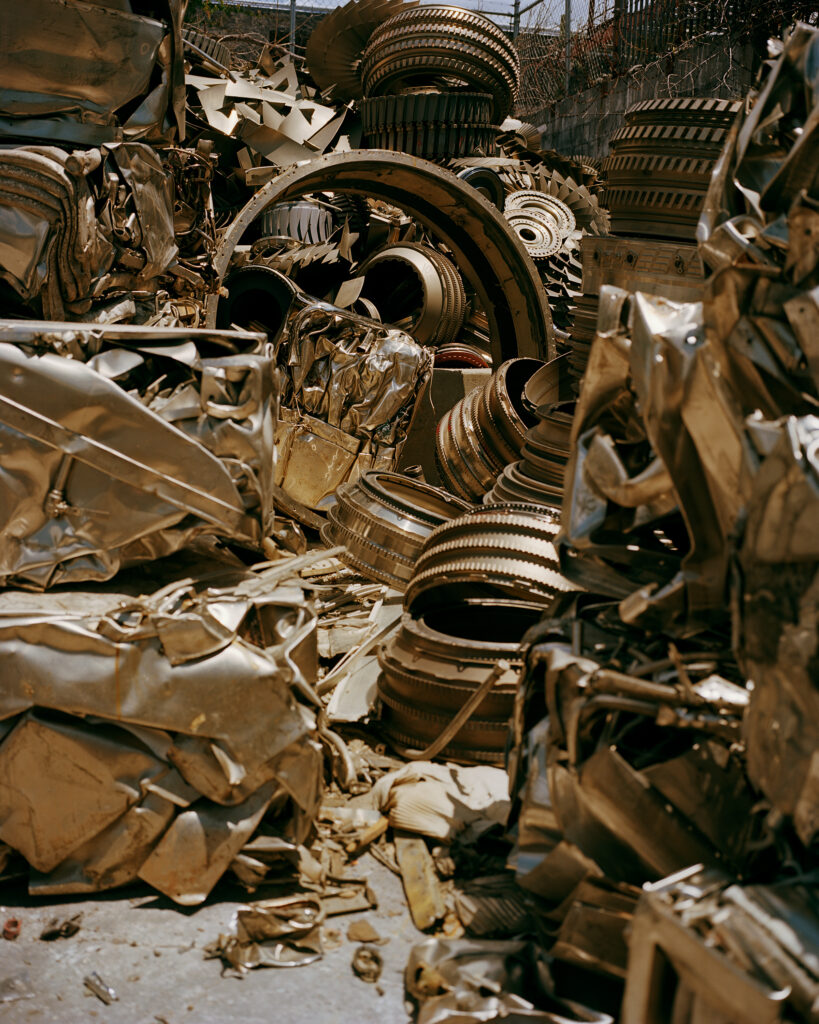

Several of these photographs explore that theme, albeit in an offhand, glancing, emotionally withholding way. Cromwell shows us an abandoned shopping cart; a pile of scrap brass; a group of hard hat-wearing construction workers grabbing lunch at a sandwich truck parked behind what might be a new condo building; a bin full of flimsy-looking, perhaps secondhand clothing; a trash pile with construction debris and what appears to be a pair of abandoned Jet Skis. Absent any contextualizing material in the form of wall labels or specific titles (the pictures are all from Cromwell’s book A More Fluid Atmosphere, published this year by Pomegranate Press), we’re left to fill in the contextual and narrative gaps ourselves with a series of questions and conjectures. Has the shopping cart been used by a homeless person, or maybe someone who simply doesn’t own a car and lives far from the nearest grocery store? Will the construction workers be able to afford to live in the buildings they’re working on? Who will buy and wear those clothes, and who won’t? Do the Jet Skis still work? Will their owners ever claim them, or have they left them curbside for good, ditched for a later, faster, more fabulous model? And if all that scrap metal could be melted down into a giant brass ring, would it encircle the city? How brightly would it shine? And will there be anyone left to grab it in this wasteland of disposable people and things?

Elsewhere the photographs inch away from the sociological toward the spiritual, although it’s possible to connect the two – a project thinly implied by the juxtaposition of pairs of images at Institute 193. In one pair, a framed print of an injured man in spandex shorts (he has badly skinned both of his knees) is dropped into a larger image of an aging security gate with both Art Deco and neoclassical decorative elements. In the second pair, a portrait of a woman in a tight-fitting sports bra leaning against a dumpster (sunbathing? resting from a run?) is connected to a shot of a car, its interior protected from the harsh sun by a reflective screen beneath the windshield. In both these shots, self-consciously athletic yet all-too-fragile human flesh comes in contact with unforgiving, solar-heated surfaces. The bruised knees might symbolize the photographer’s desire to look beneath the Band-Aids that this city plastered over its open wounds; the woman, in her carefully applied makeup and expensive-looking garments, might be a seeker grabbing a moment of stillness in the midst of this soulless place not meant for people with souls. (In a recent article in The New Yorker, it’s revealed that Cromwell found her subjects for street portraits by putting out calls for self-described “spiritual people†on Craigslist.)  Â

There’s a coolness and a neutrality in most of these images that render them more successful as conveyors of information and analysis than as givers of aesthetic pleasure. Most lack both the high drama and instant iconography of classic photojournalism and street photography (I’m thinking of Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, and Henri Cartier-Bresson) and the exquisite compositional sensibility of, say, Jeff Wall, Sally Mann, or Andreas Gursky. This is work to ponder and second-guess, not to become immersed in, and certainly not to be dazzled by. This is, presumably, intentional; ripping off Band-Aids isn’t pretty.

Except, perhaps, in one case. The show’s best photograph here, by a wide margin, is the one whose political implications are matched, and perhaps outmatched, by purely artistic concerns. The image shows several bright yellow fruits, probably mangoes, arranged on the concrete steps of a building under construction. It makes us think, of course, about who put them there, who might eat them, under what conditions, all that. But these considerations are secondary to the sheer sensuous beauty of the image: the seemingly conscious configuration of the fruits, their vibrant color, their natural and voluptuous sensuality in an otherwise unnatural, arid place. It speaks more eloquently than any of the others of the possibility of life in this latter-day land of the dead and near-dead, and it hints at the non-neutral, fully self-declared artist Cromwell might yet become. Its uniqueness in the exhibit is underscored by the fact that it’s the only photograph here printed on particle board (which gives it additional layers of earthy surface texture) and the only one that isn’t hung on the wall but, rather, leans casually against it as if it were an afterthought – the star of the show, hiding in plain sight.

In the middle of the room is another sort of outlier, a sculptural piece – Cromwell’s first, according to gallery director Ryan Filchak – made of precariously stacked, spray-painted wooden palettes of the sort used to transport boxes of food or other items on trucks or in warehouses. “Ascension,†as it’s called, curves upward in a progression of steps too rickety for anyone human, even a child, to climb. Indeed.

Installation photos by Josh Porter; all other photos by Rose Marie Cromwell, courtesy of the artist. “A More Fluid Atmosphere” was on public exhibit through December 18; may be seen by appointment through December 28, 2021. www.institute193.org