The intent of “Faculty Series: Vol. IV,†at the University of Kentucky’s Bolivar Art Gallery, is to exhibit recent work by the teaching staff at the UK School of Art/Visual Studies, not to chart the trajectory of American contemporary art over the past forty years or so. But it ends up doing both. This fourth edition of the annual show gives a subset of the school’s stylistically diverse faculty – in alphabetical order, Chad Eby, Marty Henton, Fuko Ito, Forest Kelley, Brandon Clay Smith, Hunter Stamps, Heather Stratton, and Lynn Sweet – a chance to show multiple pieces each, including, in some cases, suites or series of related works. They’re also installed, tellingly, in a sequence that steers the visitor along a path from painting and sculpture to conceptual and new media art, with several points in between.

Lynn Sweet – the UK veteran still heroically recovering from a major health crisis earlier this year (as evidenced by a certificate from Cardinal Hill Rehabilitation Hospital on display as part of the exhibit) – is positioned at the head of this path. That’s fortuitous, as he’s also clearly the show’s standout artist. His vivid, vibrantly colorful images of Kentucky river scenes are at once immediately accessible and quirkily stylized in a way that lifts them well above, and apart from, realistic landscape painting. Sweet applies pigment to canvases in these ostensibly representational pictures with a heavy yet precisely controlled hand that calls sly attention to its gestural rhythms. They are paintings about the glory and patterns of nature, of course, but they’re also paintings about the act of painting. The reductive, dabbing way he indicates directional light on the bark of the trees in “South Fork Licking River†(2019), for example, would seem almost naive if it weren’t so clearly thought out; so too the light green fringe that delineates the leaves on the trees at the top of the painting. And Sweet’s rendering of the reflections of brown trees, blue skies, and white clouds on the water’s surface has some of the graphic simplicity of woodblock printing. The artist’s sinuous visual vocabulary seems to incorporate influences from Hiroshige and Charles Burchfield to anime and graphic design, but it’s distinctly his own. The result – a shimmering, ecstatic vision of Kentucky’s rivers as Arcadian paradises and, by the way, ideal subjects for painting – is self-evidently the work of a master in firm command of his message and his medium, barely a hair’s breadth between them.

There’s a bigger gap, it seems to me, between the form and feeling of “Intersection†(2011), a massive, showily luxurious piece of Sweet’s older art furniture that simultaneously deconstructs and partakes of the tropes of Art Deco and its modernist descendants. Its array of gleaming surfaces and symmetrically massed volumes is icily beautiful and impressive as a kind of art-historical essay, but it lacks the emotional power and the sheer creative joy of the paintings. It’s on them, I suspect, that Sweet’s artistic reputation will largely rest, and rightly so.

The exhibit’s other painters, Smith and Henton, are a study in contrasts. Smith takes the biggest artistic swing in the show with his unnerving triptych “Scattering Garden†(2021), a monumental, semi-abstract piece that seems to evoke the scattering of cremated human remains in a dark field of brambles under a brooding, crepuscular sky. Look hard at the panel on the left and an ash-strewing figure may (or may not) manifest; in the middle and right panels, the ashes swirl and coalesce (or not) into shapes that might be clouds, faces, ghosts, souls. I give Smith credit for having the vaulting ambition and abundance of nerve necessary to tackle an artistic challenge daunting enough to give Anselm Kiefer, perhaps a guiding spirit in this work, serious pause. But I also feel that Smith’s everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach to materials – he applies not only oil and acrylic paint here but also hay, straw, and hair, which protrudes from the surfaces and edges of the panels in oily black tendrils – could have used some restraint and editing. (A second, similar Smith painting, “Breaking Apart†[2021], is simpler and more elegant; interestingly, it’s hung far away on an opposite wall in the gallery, as if to avoid comparison with the larger, more unruly “Scattering Garden.â€)

Henton’s trio of small, abstract, vaguely cosmic encaustic paintings on drywall plaster is all restraint, all beautifully muted discipline and decoration, and not much else. Its artistic statement is so quiet, or maybe subtle, that only one piece in the series, “Around the Planets†(2019), has an actual title. (The other two are “Untitled†and “Reworked.â€) “Sanctuary,†Henton’s unrelated, house-shaped accordion-book meditation on the theme of home, is more substantive, successful, and interactive; viewers are invited to write down their own thoughts and feelings about home and place them inside.

Ito’s “perennial’s cradle†(2021), a series combining watercolor and colored pencil on paper, feels like a companion to “Sanctuary.†At once mythic and organic, Ito’s work imagines home as a series of nests, physical and emotional, including what might be a nuclear family of snuggling sea creatures, their tentacles tenderly enfolding one another. (Elsewhere in the series, similar embraces devolve into constraint, even entrapment.) Stamps, the lone sculptor in the exhibit, inhabits adjacent thematic territory in organic, vaguely humanoid ceramic pieces such as “Nurture†(2021), which I read as evoking a matriarchal figure, and “Slippage†(2021), whose artfully flaking glazed surfaces suggest desiccated human skin.

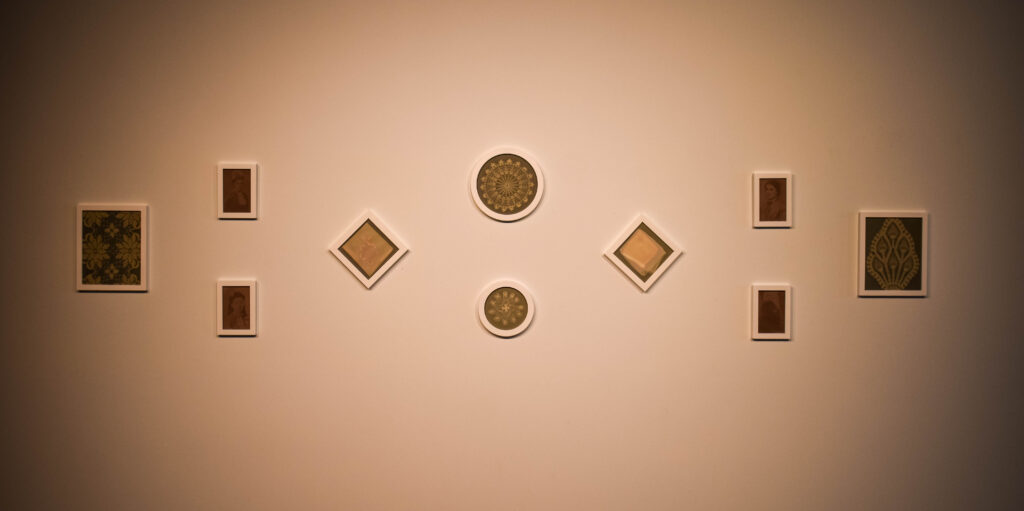

In the gallery’s second room, farthest from the entrance, the visitor encounters Stratton’s somber “Elegy of Herstory†(2019), an installation that uses ghosted impressions of handcrafted fabrics like lace doilies, deliberately faded lumen prints of archived family photographs, and a spectral video to convey the cultural and historical erasure of several generations of her female ancestors in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. It’s a moving gesture that honors women whose original surnames (and sometimes even their first names) were lost when they married and took their husband’s names or were identified on documents only as their fathers’ daughters.

The remainder of the gallery is occupied by cerebral, technologically complex, and emotionally austere new media works by Eby. These include “Phlogiston†(2021), which its wall text describes as “an ever-changing minimalist generative video piece using strategies of drunk walks, logical operators, and cellular automata rules to produce a lively monochromatic tiled bitscape.†(Got all that?) There’s also “Common Fate†(2021), a device with microcontrollers and OLED displays that spell random words in what the wall text calls “a meditation on expectations, chance, and free will.†Finally, there’s “Skärgården (The Archipelago),†a grouping of light projectors on tripods that spray quite beautiful splotches of multicolored light about the room in what turns out to be a reference to the collection of islands that is the city of Stockholm.

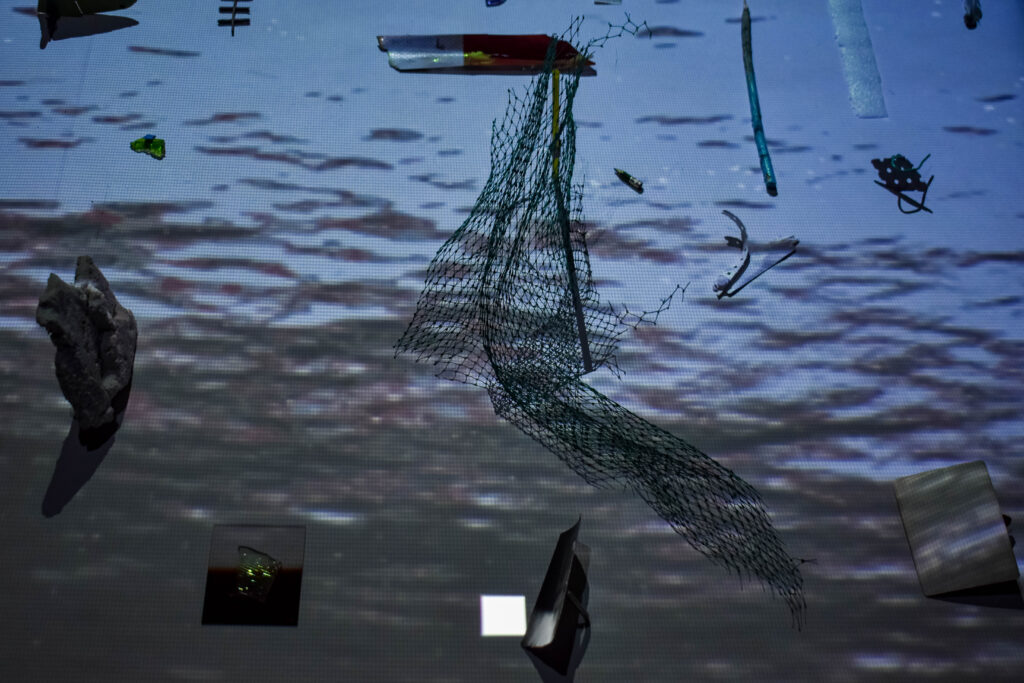

My visit to “Faculty Series: Vol. IV†– which continues through September 4 with a reception at 4:30-6:30 pm on September 2 – concluded with perhaps the show’s most complicated and most haunting work, Forest Kelley’s undated “Their Memories Also Mine.†Nestled inside a small kiosk on the border between the two main gallery rooms and featuring the work of collaborators Duygu Agal, James Enos, and Derya Yildirim, this dreamy piece uses projections, a recorded soundscape, and “ephemera,†as the wall text calls it, to suggest an ocean littered with human objects (including netting and what appears to be a box cutting tool). As I read it, rather uncertainly but with a growing sense of the uncanny, “Their Memories Also Mine†is both an environmental cri de coeur and a poignant evocation of the variety of human experience on beaches. On the soundscape, we hear snatches of mumbled dialogue as if random ghosts were passing by with sun on their backs, sand between their toes.

All Photo Credits: Kevin Nance