ÂÂÂIn her book On Longing, Susan Stewart describes the miniature as a special type of object that speaks to the nostalgia and fantasy inherent in both childhood and history. The artworks included in notBIG(4), now on display at the M.S. Renzy Studio and Gallery in Lexington, Kentucky, typify these notions. The exhibition, juried by Transylvania University art professor Kurt Gohde, presented its entrants with only one stipulation: small scale. Working in sizes of twelve by twelve inches and smaller, artists submitted works that explore the notion that, in Mr. Gohde’s words, “bigger may not be better.â€

A quick assessment of the works reveals a somewhat conservative approach on the part Mr. Gohde. Of the forty-five works, nearly half can be classified as portraits or landscapes. The miniature, especially in painted form, has a fairly consistent art historical track record. Painted portraits and small natural scenes were the affordable fine art choices of middle class collectors before the advent and wide popularization of photography in the mid nineteenth century. In a way, the exhibition pays homage to the historical miniature. Thankfully, it isn’t burdened by nostalgia for the past, but its works engage with nostalgia in order to explore and elucidate its presuppositions and effects.

The more appealing of the works in notBIG(4) represent a creative approach to the twelve inch by twelve inch limitation placed on their scale. In Mr. Gohde’s notes, he mentions one of several considerations in his selection process, that the works “NEED or TAKE ADVANTAGE OF the small scale†requirement placed on entrants. In my opinion, it is the more sculptural works that best exemplify this exploration of the exhibition’s focus on spatial limitations. Several works, including ceramic, wood, and mixed media assemblages, occupy and explore a miniature space rather than simply conform to a miniature scale. Like dollhouse models or children’s toys, they present the viewer with the possibility that within such a seemingly limited space there might exist whole worlds, imaginative or otherwise.

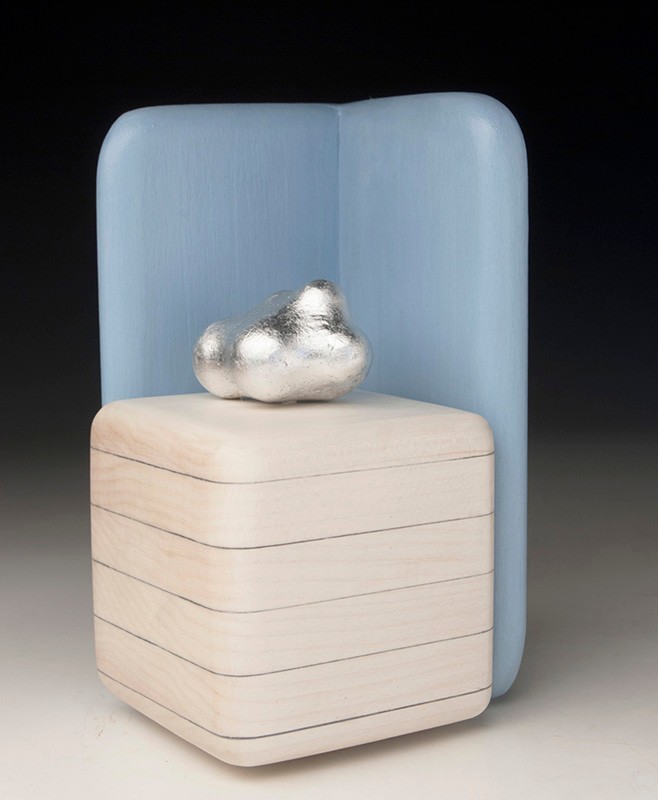

Rebecca DeGroot’s Strain is reminiscent of both Louise Bourgeois’ mammoth cast bronze spider-like sculptures and a piece of fine walnut furniture. While it could be both or neither, its mysterious nature, perhaps more akin to the micro than the macroscopic presents a fantasy grounded in reality. Similarly, one of exhibition’s honorable mentions, Critz Campbell’s Single Cloud, recalls both a wooden maquette and decorative period artifact. Again, it is a fantastical take on a natural phenomenon communicated through the imagery of both a child’s toy and technical model.

Another honorable mention, Rene Hales’ hazy and dreamy photo-encaustic Backyard Woods, is equal parts photographic record and pictorial fantasy. The encaustic’s wax  transforms the flat picture into an object with literally and metaphorical depth. In fact, several other works employ the use of encaustic, an application of wax mixed with resin, to create the illusions of the dreamy haze of age. Derek Ball’s Everyday Day, Every Hour (C1) offers a digital take on this aesthetic of translucent fogginess. The densely layered photographic object is equal parts knowable and mysterious.

Among the more traditional works in the exhibition, those of portraits landscapes, Mr. Ghode has selected pieces that run the gamut from Clint Wood’s City Corner, a colorful and somewhat flattened rendering of an anonymous street and its buildings to the nearly abstracted natural effects of Karen Spears’ Floating Foliage.

Similarly among the portraits are several striking explorations of sizing and scaling images of the face. Irene Mudd’s Joan and Todd Fife’s Ghost Man both treat the details of the human likeness like pixelizations, though composed respectively from yarn and the stains and smudges of graphite and coffee. Still recognizable, the features point to the difficulties of certain media to accurately replicate and render the human image.

Of course, there are other works in the show that don’t necessarily treat miniaturization as simply an issue of size or scale. Tom Pfannerstill’s Crushed Starbucks Cup is in actuality a finely detailed painted wood sculpture that both elevates and eternalizes street trash as art object. What appears as stains and damage are the specific details of a meticulously crafted and considered totem of the vastness of urban waste and global consumerism. Likewise, Allison Tierney’s 10/11/2015, a wood panel layered with latex paint that resembles the leftover scraps of a painted canvas, is both painted object and paint as object. Like Pfannerstill, Tierney offers much more to the viewer than what is simply visible in her painting, and recalls Marilyn Minter’s early photorealistic painted floors and sculpted polaroids, playing with the discrepancies between what is seen and what is experienced.

The work awarded the exhibition’s best in show, a painting by Sean Ware titled With Clouds in Sight, seems an overly safe choice, considering its subject matter is neither a unique nor particularly engaging mediation on the miniature schema. While one of the more technically impressive works on display, it lacks the specificity that the miniature itself implies, that of the somewhat fantastic and nostalgic possibilities of they might contain. There are more interesting and fruitful works for the viewer here, works that eagerly attempt to find purpose in their relative smallness.

In the end, the exhibition and its space, though itself small and somewhat cluttered, allows the works their own room to breathe, and helps to further encourage viewers to consider the individual worlds they represent. While not everything on display succeeds in expanding and developing the rhetoric of smallness, the dollhouse specificity of many of these miniatures, especially the sculptural works, makes this exhibition seem much larger than it appears. The opportunity to enter, inhabit, and participate in the fantasies of self-contained and self-sufficient worlds gives notBIG(4) enough of a reason to be seen.