I became acquainted with the work of Aaron Lubrick on a Zoom call of the Artists Breakfast Group, which has met weekly for over 30 years. Retreating online due to COVID, the group has taken on a new seriousness. Recent topics have included penetrating discussions of art world leaders like Vija Celmins and Martin Puryear, presentations of works by Louisville artists, valuable discussions on responsibilities incumbent on the creative community, and the relationship of art and politics. Aaron had been invited to show his work online by Tom Pfannerstill, the Zoom host and across-the-alley neighbor.

In early October I had the chance to visit his studio in Louisville’s Highlands neighborhood, close to Cherokee Park. Aaron’s backyard studio is a white cinderblock building with high ceilings and wide clerestory windows to the west. It has a garage door opening on the east side, which was kept up and open for my visit. We moved chairs to the shade and talked outside before looking at the paintings inside. Aaron describes himself as a “perceptual painter†allying himself with other artists united by their belief in direct observation as the starting point in making art. However, slavish realism is not the goal. Scott Noel, a teacher of Aaron’s, has written: “We recognize rightness and one of the attractions of observational painting is the way visual truth is experienced as surprise…. A good picture specifies something about the conditions of relationship that prevail in an appearance and embodies these discoveries in the physical terms of the painting itself. From the outset, mimesis couldn’t be copying, but a reconfiguring of experience in terms of sculpture, painting or drama. In this sense, observation – a close attention to the phenomena – has been necessarily imaginative.â€

Aaron was an undergraduate at the Columbus College of Art and Design and received his master’s degree from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He is currently an Associate Professor at Spalding University. What compelled my visit were the images he showed online of his Ohio River paintings; it’s an ongoing theme for him. His engagement with the river goes back to his childhood when he went fishing with his father and twin brother on his dad’s 14-foot boat with a 6-horsepower motor. He takes his own three sons out on the river on a Boston Whaler. He is particularly entranced by the openness and scale of the riverscape.Â

One of his professors at the Columbus School of Art, Neal Riley, quoted Whistler, “…paint the air around the object.†Lubrick is a connoisseur of Ohio Valley August humidity. “The moisture tends to melt things,†he remarks. “Dan Walking His Dog,†2013, is a good example of Lubrick’s depiction of the dissolution of form in the heavy summer heat. A man is seen in the foreground on the river shore accompanied by a dog. Chords of complementary colors, rose and aquamarine and blue and yellow, key the painting. The crepuscular light of sunset is rendered in thick ropes of pigment, fragmenting the form of the man and his dog in the foreground. Seen against the light, the figures are partially obscured.

The standing figure is to the right of the painting’s center, and his dog occupies the lower right corner. In the upper right corner is a tree atop a slight rise with more foliage. The foreground man, dog and fragmentary landscape on the right are juxtaposed against the left half of the painting with its broad expanse of river and sky. In the distance is a towboat with barges indicated economically with four or five strokes of white and blue. The opposite shore is reduced to bands of green and blue that anchors the left side of the painting but fade in the atmospheric perspective.

Lubrick’s practice can be roughly described through four aspects or principles (which seem to take place at once rather than sequentially): observation, the life of the medium, the artist’s heritage, and private narratives.Â

The first is observation. Joan Didion famously wrote, “I write entirely to find out what I am thinking, what I am looking at, what I see and what it means.’’ Similarly, Lubrick paints to give what he perceives its fullest possible expression. Compositionally, “Dan Walking His Dog†invites you in as far as the towboat in the distance and then escorts you back to the surface because of the frontality of the figure and the density of the pigment. The viewer’s passage through the painting is a protracted exploration. Although his smaller paintings are done from life, his contemplation is digressive rather than following a linear path. Lubrick quoted the late William Bailey who remarked in a lecture in Louisville that “painting is like having an argument with a really close friend. The result is a compromise between you and the friend.†Lubrick added, “I do a lot of talking. I ask the picture what it wants.â€Â

A second aspect, or principle, of the Ohio River pictures is their engagement in the life of the pigment, an aspect of the artist’s digressive, searching approach to building the paint surface. The artist has noted, “If I am not seeing the medium in a new way I can’t make a painting.†During his time in Columbus, Aaron frequented the Columbus Museum of Art. His favorite works were the George Bellows oils in that collection, with their rich and rugose surfaces, and Edward Hopper’s “Morning Sun†with its broad planes and coloristic exactitude. The skin of the model (Hopper’s wife) bears hints of green, reflecting the wall color of her room.

In “Dan Walking His Dog†the wedding of sight to touch is apparent in the juicy squiggles of paint to denote passing clouds, and the overlapping pink, blue and white strands suggesting the Ohio’s current and the reflection of the setting sun. In contrast, the stasis of the figure of Dan is indicated by extended strokes of brown and red-orange defining his contours. Lubrick’s painterliness is especially evident on the edges of the surfaces he is depicting; overlapping colors and brush marks modulate the corporeality of the man, emphasizing his role as an object lesson in the reflection of light.

The enrichment and variegation of Lubrick’s surfaces adds to the here-and-now/present tense quality of his work. He treats his panels and canvases as a zone of incidence. He does not see detail in his work as transcription of a physical fact but a mode of viscous color fiction. In “Pole Leaning Toward the Ohio†the series of marks mediate between visual data and its free transcription, yet always seem to bear witness to Lubrick’s commitment to the optical truth of the painter’s experience, especially as conveyed in the kinesthetic impressions of the motions of the brush. An improvisatory quality is linked, surprisingly, to evidence of painstaking craft – the work in the work of art. But Aaron admits that when his paintings are finished, they have not necessarily reached “certainty.†But invariably they do achieve a distinctive paint character.

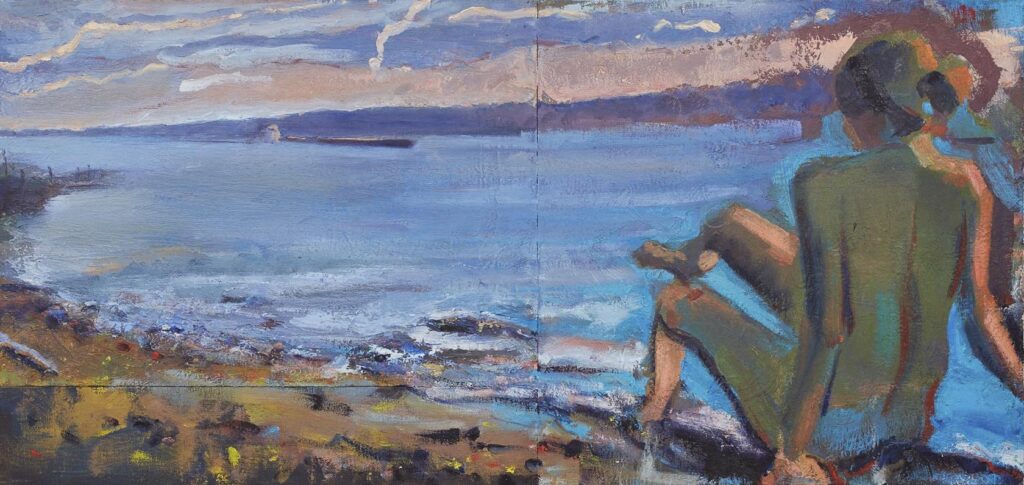

A third step, or principle, is to remember the conventions that are the artist’s inheritance. The art incorporates information from other realms besides perception of the landscape. For example, the proportions of the figure of Dan – defined shoulders, narrow waist, muscular legs – recall 5th century BCE Greek kouros sculptures of young men. Comparably in “Autumn Bathing with Passing Barge,†the pose of the woman in the foreground echoes one of the figures in Renoir’s “Grand Bathers†in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. When someone remarked that some of his paintings of the American West had a 19th century color palette, Lubrick took it as a compliment. In the foreground of “Pole Leaning Towards the Ohio,†there is a brilliant passage of curves and dashes in pink, orange, magenta, luminous red, and yellow. To my eyes it recalls the gestural calligraphy of Jackson Pollock’s 1940’s paintings, “Male and Female,†and “Pasiphaë.†But Lubrick’s far-ranging palette always serves the end goal of being precise about the quality of light in his landscapes.

A fourth aspect of Lubrick’s Ohio River paintings is their metaphorical content, or private narrative. Lucy Lippard wrote in her 1997 book, The Lure of the Local, “Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within the map of a person’s life. It is temporal and spatial, personal and political.†Lubrick’s Ohio River paintings are freighted with public and private narratives. Individual works appear to be in a state of continuous evolution, as if perpetually in the middle of a process. To that end, Lubrick’s practice seems to me to stay open to emotional inflections, quite apart from their descriptive function. “Farewell to Harvey,†is acrylic on canvas and the largest (60â€x 72â€) of Lubrick’s paintings I have seen. It was inspired by a visit to the Gavin Brown Preserve, a wetland adjacent to Hays Kennedy Park in eastern Jefferson County. The Preserve has 1500 feet of Ohio River waterfront, and has a rich profusion of plant life, including green ash, red maple, native pin oak, swamp dogwood, water primrose and plantain. In wet weather the pathway to the water’s edge is frequently impassable.

Aaron’s larger paintings are done in his studio and typically take a year to complete. “Farewell to Harvey†is constructed with receding bands painted with staccato vertical strokes. In the foreground underbrush is conveyed in long passages of blue, gray, carmine and mauve, alternating warm and cool tones. In the middle ground beige and taupes dominate. At the edge of the river are scumbled blacks and the Ohio itself is azure and cerulean blues. At the top of the painting is a band of passing black storm clouds with white clouds breaking through. The painting walks a tightrope between representation and abstraction. To me, the barrier between the viewpoint and the river suggests an allegory of an aspirational goal hindered by an impassable pathway, or alternately, the sense of resolution when sunlight returns after a storm. Open-ended as to possible readings, Lubrick poses the question of the unseen in the seen: the synthesis of observation and memory in “Farewell to Harvey†speaks to an introspective meditation that uses as metaphor a place prominent in his biography.

Like another contemporary Ohio River painter Ray Kleinhelter, Aaron Lubrick is re-interpreting the river in very personal terms. It is an assertion of the specificity and particularity of a given geography, as opposed to the Amazon Prime homogeneity of much American life. It is also an assertion of a regional place in the global art dialogue, by working at the highest level of ambition and using the Ohio River’s many characters – by turns enigmatic, portentous, threatening or merely picturesque – as the departure point for an internalization, transformation and intensification of raw data to make memorable art.

Photo credits: Aaron Lubrick