For nearly two decades, Lakshmi Sriraman was known in Lexington primarily as a teacher and performer of the traditional Indian dance known as Bharatanatyam. This dance uses a strictly coded set of movements, postures, gestures, and eye-shifting facial expressions to tell the stories of ancient India, with themes and lessons still pertinent today. Growing up near Chennai, in southern India, Sriraman (pronounced Shree-RAH-men) had studied the intricate, highly structured style of dance since she was a little girl of 7 or 8, often performing in school programs. “I think I was naturally drawn to dance,” she recalls in an interview at her home near Masterson Station Park in west Lexington. “Anything you taught me, I would do it right then. So I picked it up very fast.” At some point, like most Bharatanatyam students, she was expected to perform a two-hour debut recital, called an arangetram, with a full orchestra. “It literally means ‘ascending the stage,’” she recalls. “But at that time my father said, ‘I don’t have money for this.’ So I quit learning at that time, but I never quit dancing.”

When Sriraman moved to the United States in 1994 to get an MBA at the University of Texas at El Paso, and from there to Atlanta to work as a business consultant, she resumed her dance training and gave her arangetram at the age of 33.

A decade later, after relocating to Lexington with her husband and son, she began performing at venues around town to enthusiastic audiences composed largely of the city’s burgeoning Indian American community, whose parents flocked to Sriraman, begging her to teach their daughters. And so, the Shree School of Dance was born. Suddenly Sriraman was giving weekly lessons in a rented space to as many as 40 girls, young women, and a few older adults from around Kentucky, passing along a 2,000-year-old art form that, although it predates Hinduism by more than a millennium, remains flexible enough to consider startlingly modern topics.

“The kind of subjects that I choose for my dance are anchored in things that I want to talk about – the topic of gender, for instance,” she says. “Gender traditionally is a binary, male or female, but there is an iconographic image in Hinduism that is half man, half woman – half Shakti, half Shiva. The left half is Shakti, the right half is Shiva. There are many layers of understanding and philosophy within that imagery. One of the things it says is that nobody is fully masculine or fully feminine. Whatever your body’s gender is, we all hold energies of both masculine and feminine – the one that’s nurturing, the one that’s doing. To me on a lot of levels it talks about gender fluidity, it talks about the ability of humans to bring forth what’s needed. It cannot be put in a box of masculine or feminine. I use that iconography, then, to frame it, in a way. I’m not proselytizing, I’m not saying this is what it is. I’m asking how do you talk about this? What does this mean to you? What does it awake in you?”

This went on for several years. Then, about four years ago, two things happened.

The first was that Sriraman accepted, finally, that it was time to stop running a large dance school built around herself as the sole instructor. “The students were thriving, but I was not,” she admits. “For three years I wanted to close my school down, but I couldn’t because I thought I was abandoning all these children, right? I had to take a look at: What is my life’s purpose? Am I furthering my purpose? And I realized that so much of my energy was going into keeping the school running, and I was cutting off a lot of my own creative work. I was constantly tired. And I came to a point where I was resenting it. And I said no, I can’t resent this. This is a great gift in my life, to be able to teach. So I thought it was time to quit with the school, to not do it the way I was doing it.”

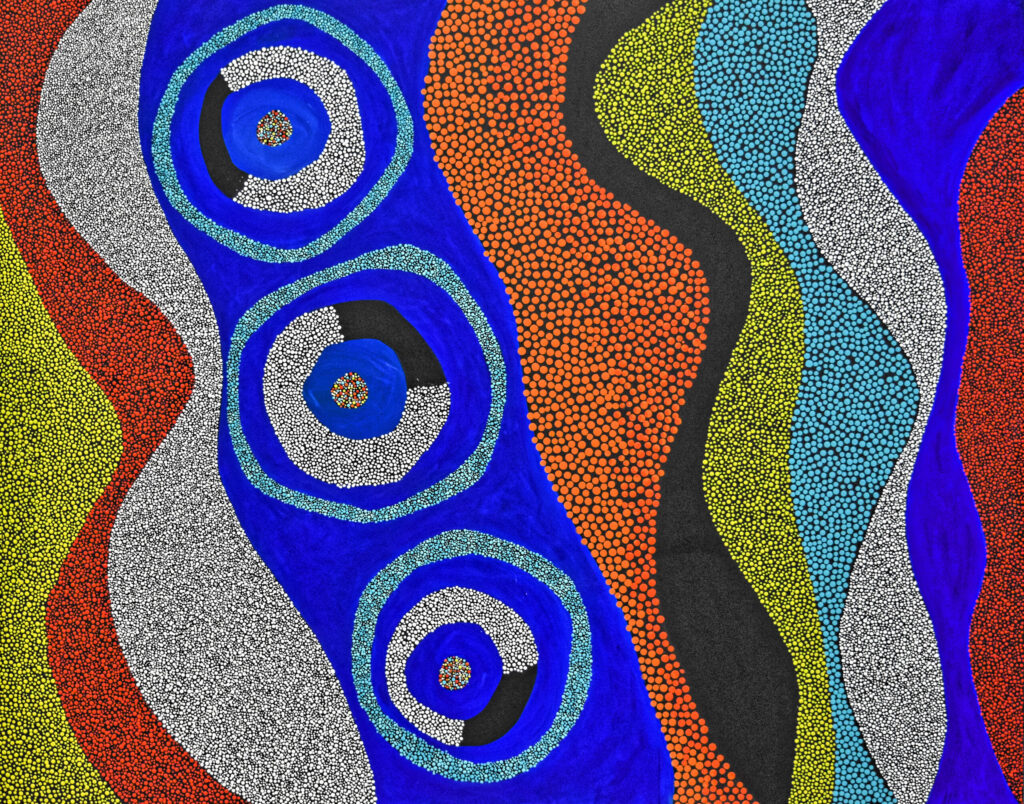

The second thing that happened was that Sriraman went to a rock-painting workshop, where she learned the dot painting techniques associated with Australian Aboriginal artists.

“I came home from that workshop,” she says, “and I just couldn’t stop painting.”

***

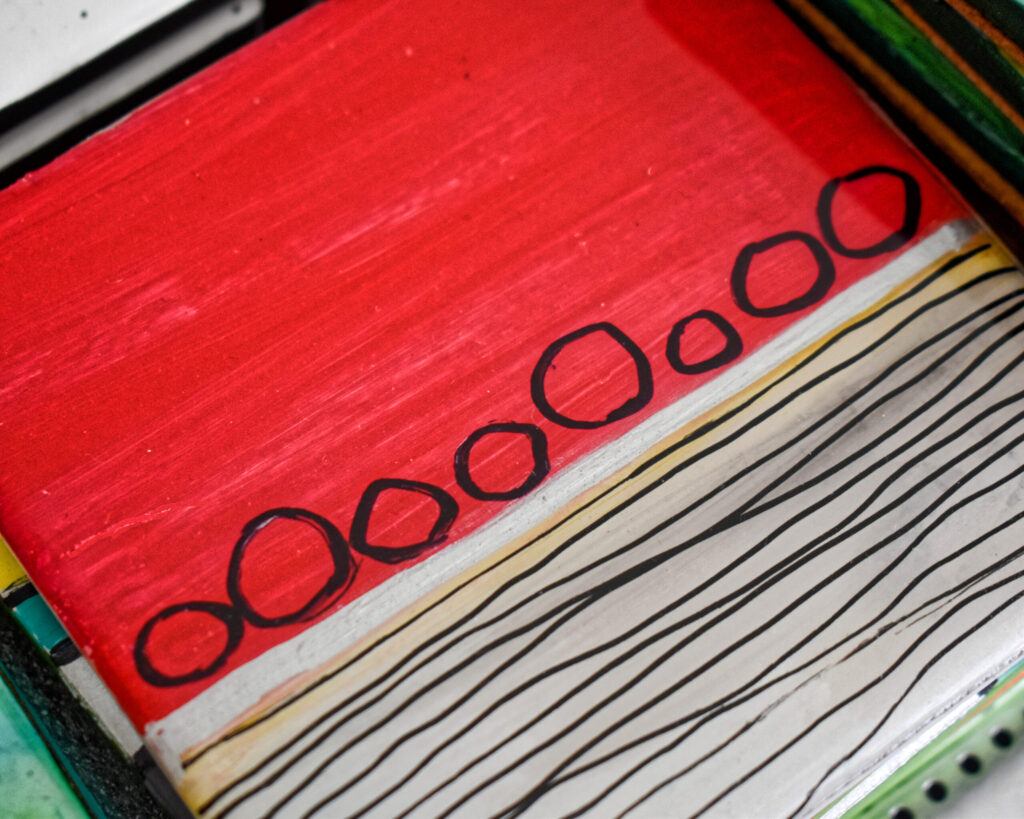

Sriraman threw herself into the work, quickly making dozens of paintings. Many were inspired by Indian mandalas, using the dotting technique, whose application she found unexpectedly meditative. “I found the practice of dotting a mandala so calming, grounding, balancing. At that time that I was going through a lot of inner changes, including some relationship stuff, and doing the mandalas helped me heal from a lot.”

She was entirely self-taught. “I’ve not had a single class,” she says now. “I’ve just taught myself a lot by watching, by practicing, by working on my own, making mistakes and learning from them. It’s just, How about this? How about that? It’s intuitive, and I’m not following any prescriptive method. And that is very liberating for me, in part because on the one hand, I’m practicing this traditional art of dance that takes years of training [she still has a few private dance students whom she taught, during the pandemic, on Zoom] and on the other hand, I’m totally experimenting with visual art, making it up as I go.”

As with her dance training as a child, her progress as a visual artist was swift. Before long, Sriraman was selected by a jury to participate in the annual Kentucky Crafted art show, “which opened a lot of doors for me,” she says. She began to exhibit her work in galleries. “When I first saw her work in 2018, I was immediately impressed by the beauty and the sincerity and the thought process behind it,” says Mark Johnson, president of Art Inc. Kentucky, a non-profit arts incubator that recently opened a retail gallery, ArtHouse Kentucky, in Lexington’s East End. “Almost from day one, we felt her work was ready to be displayed, in part because it’s so distinct. When you look at her work, you know it’s hers.”

Celeste Lewis, executive director of the Pam Miller Downtown Arts Center, was also struck by the sheer velocity of Sriraman’s development. “Lakshmi’s come a long way in a short amount time,” Lewis says. “She’s soaked up so much information just by experimenting with different colors and different textures, and she’s not just experimenting and flailing and falling; she’s experimenting and hitting it hard. As someone who went to art school and spent years trying to hone my craft, it amazes me that she has picked this up and is running with it, like an athlete. No, she doesn’t have years and years of training, but she’s really good. And she has a depth to her work that, to be honest, really surprised me – not because I didn’t think she could do it, but because I thought it would take her longer to get there.”

Now Sriraman is among the most-exhibited of Lexington artists, with large- and small-scale work, including paintings, prints, cards, jewelry, and coasters currently or recently on view at ArtHouse, Base249, the Downtown Arts Center’s City Gallery, ArtsPlace, the Kentucky Theatre, the Artique Gallery, and the Kentucky Artisan Center in Berea. The City Gallery plans to mount a solo show of her work in August and September of 2023.

“I’m thrilled to death,” Lewis says, “to watch her becoming the visual artist that she is.”

***

Now in her early 50s, Sriraman paints in total silence, on canvases laid flat on the table in the dining room that she has converted into a home studio. “I don’t like to listen to anything when I’m painting,” she says. “I go into the silence and into the process. I have an intent to bring a certain energy to it, but it’s not a concept. I’m not thinking where to place the dots. It’s like tai chi, right? You know the movements so well that you are not in the movement anymore. You are in the space between the movements.”

The movements, in her case, are mainly of two sorts: first, the brushstrokes with which she lays down backgrounds (often black) and large shapes (often red, blue or yellow), and second, the small, delicate, precisely placed dots of acrylic paint extruded from a small tool with a metallic tip. None of this is planned, she says, and that, in turn, is by design. “I don’t think in terms of visual weight,” she says. “I don’t think in terms of balance. I don’t want to visually make those decisions up front. I don’t have a picture in my mind of what it will be. It just all happens as I’m doing it.”

Instead, Sriraman works in a state of mind that she describes as a kind of concentrated presence that is also, paradoxically, a form of absence. This manifests itself in her work as a performer – in which she always leaves room for improvisation, surprises, random discoveries – and as a painter. “I always want to be available to that,” she says. “As a photographer, you know if you go to photograph a wedding, say, and all of a sudden you see this child enjoying her cake. You are not there to photograph that, but that moment is so special, and if you are present, you will be able to photograph it. And to me, painting is like that. If I decide how this painting is going to look right now, I have cut out an immense capacity to create right in that moment, because this is how it’s going to be. I don’t know if this is how it’s going to be. Right now, this is a possibility. Right now, this is an opportunity. Right now, I know that this is a place where I can disengage so that I can engage. And so my work is a purely intuitive process. I go into it, and many times I don’t know what I’ve got until I come back to myself.”

Where do you go, I ask her, that you must come back from?

“I don’t know,” she says, and laughs merrily. “I’m in the dark, mainly. In the dark.”

***

Equally unplanned and mysterious is the matter of imagery in Sriraman’s paintings. The dots line up in serpentine rows like flowerbeds in a garden or, more often, in concentric circles like tree rings or ripples in a lake. They swirl and surge and accumulate, filling the spaces between the bulkier masses in the paintings. Sometimes the dots clump together so densely that they become masses of their own; sometimes they form great spinning whorl shapes like those in the starry night skies of Vincent van Gogh, or stack on top of each other in a way that evokes rock cairns or, as some of her titles suggest, Buddha. Other times they conjure landscapes, often with bodies of water flowing through them – an archipelago in the ocean here, a stream bridged with stepping stones there, or deserts, vaguely reminiscent of Georgia O’Keeffe’s southwestern landscapes. Still other times, they bring to mind fossils and geologic layers at an archaeological dig.

“They seem all very landscapey to me,” Lewis says. “She used to do things that were more spacey-looking, much more cosmic. I saw stars, the moon, the Milky Way. Now it’s gotten much more terra firma. I see a lot of boulders.”

To Sriraman’s eye, while she’s painting, there are almost never skies or galaxies or islands or oceans. “In my mind they are abstract,” she says. “I think the landscape idea is an interpretation of my abstraction. I do not seek to paint landscapes.” The large painting in progress in her studio on the day of our interview features several large red masses suspended in an expanse of black. It makes me think about blood cells passing through an artery, or a solar system of red planets glowing like Mars. It makes me think, too, about the color-field paintings of Mark Rothko, who is said to have had a complex system of meanings and feelings that he associated with different colors, in particular black and red, as dramatized in John Logan’s 2010 Broadway play “Red.”

The red masses in the painting, I say to her, are they stones in a dark lake?

No, she says.

Are they red planets in a night sky?

No.

What are they, then?

“They are red surrounded by black,” she says.

Once the paintings are completed, Sriraman does sometimes give them titles that suggest imagery. One of the most striking “landscapey” works recently on display at Base249, for example, is called “Oasis,” while two other very recent works find her applying the dotting technique to images of leaves.

And occasionally, imagery emerges unexpectedly and yet so clearly that even the artist cannot deny it. A large canvas painted in connection with a women’s festival at the Lyric Theatre & Cultural Arts Center, for example, surprised her by manifesting not just communities of women represented by dots, as she had been thinking, but individual women: several of them. “After I painted it, I thought, I see a face looking down,” she recalls. “And then I started seeing a lot of other women’s faces. I did not make these faces, but they started popping up.”

She titled the painting Many Faces.

***

Sriraman’s predominant focus on abstract, non-representational work does not mean that it lacks content, however ineffable and difficult it may be to articulate, or that it’s without context. True, it has few conscious art-historical influences. When people tell her that a painting of hers reminds them of some famous artist’s work, she says, “Who’s that?” “And then I go and google that artist and see, oh yeah, there are a lot of similarities,” she says. “But my work is not intentional that way.” Asked whether the dots are in any way inspired by the work of the pointillist painter Georges Seurat, who employed dots of paint to create masterpieces such as Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86), Sriraman shakes her head. “From what I’ve seen of his work, he uses dots to create not abstract paintings but landscapes, which is not my intention.”

So what is Sriraman’s work about? It’s no reduction to say that it’s about her – all that she was and is and is becoming, as an artist, a woman, a feminist, an environmentalist, an activist. “I believe that we’re all inspired by everything that we see and experience,” she says. “I have integrated a lot of the things I have seen.”

These include her increasing involvement with contemporary social issues, such as social justice for women, minorities, and the poor, and the push for diversity and inclusion in many parts of society, in America and her native India, particularly during the pandemic. “So, with COVID, when so many societal structures – structures that we have sort of grown numb to, like how healthcare works – started falling apart, it gave me so much to think about: the paradigm of racism, the paradigm of the haves and the have-nots, all these things on a large scale. How do we as a society deal with these things, how does the culture deal with it, humanity deal with it?”

For example, in southern India where her elderly parents and other relatives still live, she notes that the pandemic has been a disaster that has disproportionately affected migrant construction workers. “A lot of construction stopped during COVID, but the people who hired them made no provisions for them to go back home, so you had millions of people walking for months to reach their home. And many died on the way as well.” Locally, Sriraman recently served on the advisory committee for CivicLex’s new Civic Artist in Residence (CAIR) program, concentrating on ensuring diversity among the selected artists. (You can learn more about the CAIR program elsewhere on UnderMain.) Her Facebook page has many references to activism of several kinds, including social and racial justice and LGBTQ issues.

And if her art is informed by these outward observations of the world, “My work is also inward-looking,” she says. “I’m always looking at what it is that I’m creating, why I’m creating it. So many things made me think of my role in all this, and wondering how I can use my art to ask questions about all this. I don’t have all the answers, obviously. But I’m part of the problem, so I’m trying to be a part of the solution. For me, it starts with asking questions of myself and of others. And I believe that the world I create for myself and for those who I touch, will only be as vibrant as my questions are, is only going to be as deep and meaningful and love-filled and equitable as my questions are.”

Most of all, perhaps, Sriraman’s art expresses her desire for healing – for people, for the planet, for the universe. “When I apply the dots, I think about all the things that need healing, all the things that I’m grateful for,” she says. “For example, I’m grateful for the women in my life – my mother, my sister, my teachers. I think about that woman I met in the grocery store. Or I might think about women who are suffering from breast cancer, or who have lost their child, or whatever it is. I think of all those things and make them into a painting. So it becomes a prayer for healing the feminine. It becomes a prayer for women.”

Her website, https://lakshmisstudio.com/, has several of her early canvases listed in a variety of categories including “Prayer Dots,” “Buddha Dots,” “Frozen Fire Dots” and “Pebbled Dots.” “I need to update my website,” she says with a laugh. “I’ve come to understand that all my dotted paintings are prayer dots.” She compares the intention of her painting process to that of Reiki, a Japanese form of alternative medicine whose practitioners are said to heal their clients by channeling energy through their palms. “I’m not a practitioner of Reiki, so I don’t know,” she says. “But what I do know is that to me, these are prayers that are alive: prayers to God or whoever you recognize, something that’s beyond what we can see. They are my calls for healing to the universe.”

***

As if painting and dance weren’t enough for this multi-faceted artist to juggle, Sriraman spent much of the pandemic year finishing the creation of Neeri, a solo performance piece funded by a grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Originally intended to be performed live at the University of Kentucky and Berea College, Neeri was instead recorded without an audience at the Pam Miller Downtown Arts Center’s Black Box Theater and broadcast on Zoom by Berea College in May.

In the part-scripted, part-improvised piece, created in collaboration with the Tamil theater director Srijith Sundaram and the Lexington writer and activist LeTonia Jones, Sriraman takes the stage as an Indian woman who begins by announcing, “I come bearing a river.” When, she wants to know, can she ever put it down, and where? “As long as I’m a woman,” she says, “I’ve been carrying this river.” Neeri – whose name is a version of the Tamil word neer, meaning both water and feminine energy – is at once a specific woman, an Everywoman, and the embodiment of rivers and, more broadly, of nature itself. All are threatened by decision-making processes dominated by men: an imbalance, among other things, of Shiva and Shakti.

Neeri is aware that some consider her ridiculous. “There are many that laugh at me,” she says. “They follow me just to mock me.” She turns on the unseen oppressors, fixes them with a stare. “Stop it!”

Sriraman says now: “My theater work comes from the space of asking questions of patriarchy. The river is a metaphor for dreams, aspirations, joy, celebration, life itself—of the feminine in this world. It’s also eco-feminism, the literal rivers we are trying to safeguard. Humanity doesn’t take care of these natural resources very well. We take it for granted. So Neeri asks, Where is it safe for me to place this river? When can I just let go and say, okay, the river will flow fully from here on, and I don’t have to take care of it?” She frowns. “These are things that have been stewing in my mind and in my process for a very long time. Who safeguards the interests of those who don’t have a voice? Who stands up for them? Who speaks for them?”

The performance expands to include the Black Lives Matter movement and other social justice themes expressed in spoken-word pieces by Jones, who’s now collaborating with Sriraman on a second creative project for Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC) women writers. “There was something magical about hearing my words on Black Lives Matter, for example, as part of a show about a South Asian woman,” Jones says. “It helped me see that the struggles of communities of color are universal. I can’t just pay attention to the oppression that’s happening here in America. I have to see it as global, as transcending boundaries, and it’s Lakshmi’s spirit that does that, connecting women’s voices across race.”

The most electrifying moment in Neeri, as I experienced the video, comes as the protagonist is musing, with mounting anger, about the objectification (and through it the belittling) of women.

“They say women are beautiful,” she says. “Sweet as honey, soft as silk.”

And here she laughs loudly, derisively, bitterly, chillingly.

“I’m beautiful, yes,” she tells us. “But I am so much more than that.”

All Photo Credits: Kevin Nance