With the launching of the American Women’s History Initiative, Because of Her Story, the Smithsonian Institution states that its intent is to: “Amplify women’s voices to honor the past, inform the present and inspire the future.†So I don’t think there could have been a more appropriate time (Women’s History Month) for me to visit with Louisville multimedia studio artist Skylar Smith, whose work graphically signifies the Smithsonian’s mission to tell stories that “deepen our understanding of women’s contributions to America and the world, showing how far women have advanced and how we as a country value equality and the contribution of all our citizens†(Smithsonian Office of Communications & External Affairs).

Given our current political climate, these words may sound vacuous, hypocritical, or downright fake. Not so, though, in the context of Smith’s work in the duo exhibit, Personal Is Still Political, at Spaulding University’s Huff Gallery in Louisville last spring where she brought into full play what she describes as “human-scale politics that influence perception.†And because Smith’s regard for intersectionality encompasses gender and race as well as the subtle and overt ways in which discrimination becomes manifest, the scope and impact of her work are considerable.

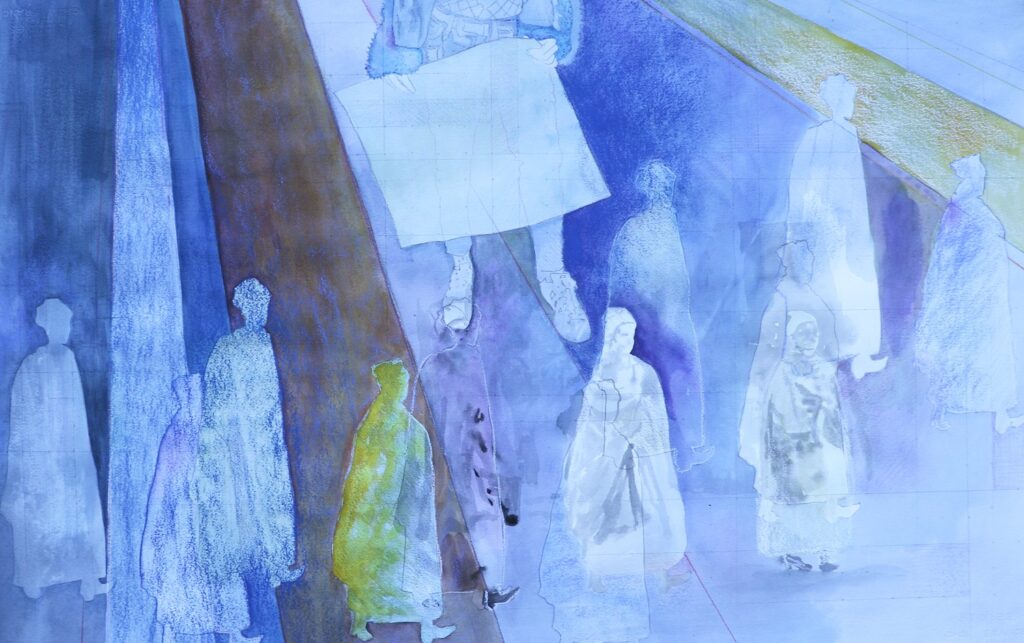

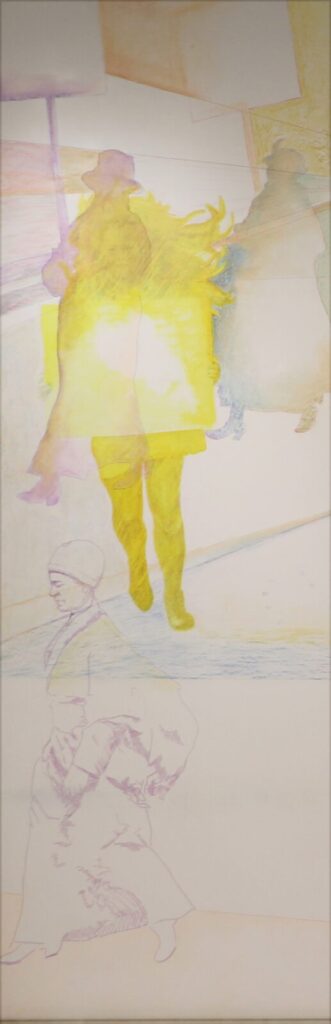

Smith’s transition from her earlier 2016 pre-election abstract work was initially inspired by the Women’s Suffrage Parade of 1913 and the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, granting white women the right to vote. But she says the turning point for her was the Women’s March in 2017 because no one was expecting it to happen. It became one of the largest protests in the history of this country—a positive act stirred by negative political actions that unified women from a variety of ethnic and cultural backgrounds worldwide.

On Personal Is Still Political, Smith comments that the 2016 presidential election opened her eyes and that she “had to move out of the abstract into the difficult process of making work about this moment in history and be somewhat objective rather than emotional. I wanted to be very clear about what statement I was making and what I was responding to. I wanted my work to be educational and provide the potential for the viewer to think about ideas in a different way, to experience some kind of transformation or exploration of thought.†She points out that by walking around and between these banners you are participating in marches that span decades not only in protest against discrimination, misogyny and the dehumanization of women, but for human rights as well.

Smith painted these banners with image overlays on both sides of large sheets of vellum and as light passes through this translucent material, the streamers not only edify but radiate a palpable spiritual tone that challenges the viewer’s sense of awareness, especially when viewed in a single space as shown in the photo above. Essential to her point of view, Smith wanted the personal and politically charged takeaway from this show to be: “It’s not okay to say that some people can be oppressed but not you.†The same holds true for her work in other media, particularly her more abstract Suffrage paintings.

Although she works in a variety of media, including photography, video, and installations, Smith gravitates toward the immediacy of what she loves most—drawing and the materials used to paint and draw: graphite, charcoal, colored pencils, pastels, and water-based media, such as acrylic and ink. By combining wet and dry media, as in Ladies Remember, she is able to create a dichotomy and establish a dialogue within a given piece where tension emerges between the wet marks that are erratic and fluid and the dry marks that are more precise and controlled. However, she says she often chooses a wet medium on wet paper over dry because “it creates a visual manifestation of something I cannot control or expect and for me that’s like life, one percent within our control and 99 percent out of our control.â€

The surface she works on, be it vellum, paper, or wood, is crucial since it dictates what she can and cannot do. For instance, different types of paper—cold press with a rough texture or hot press with a smooth surface—render distinct effects based on the medium she applies to it.

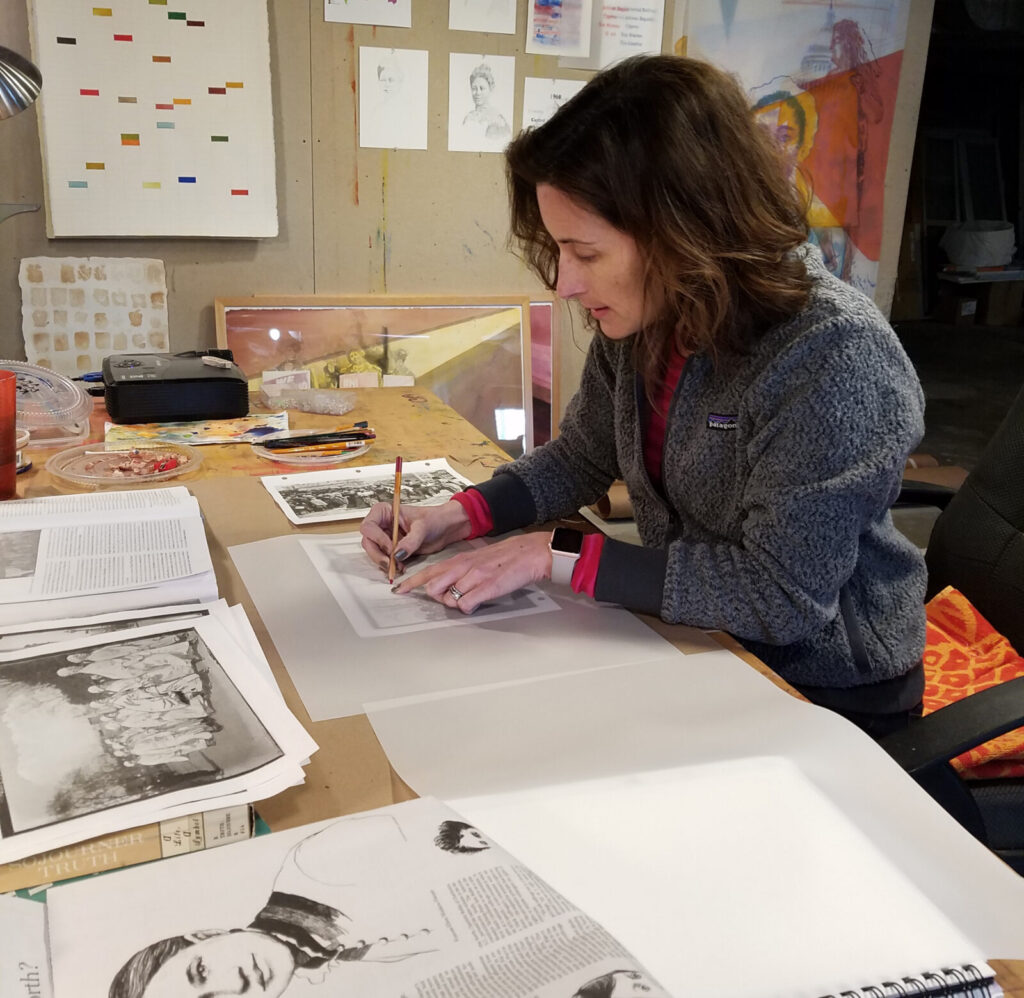

As for me, I chose this particular photo of Smith at work in her studio because the harsh light striking her hair, shoulder and arm illustrates a salient point she emphasizes about her work from her Accumulation and Micro/Macro series. “Everything mimics and echoes something else. The only thing that is different is the scale.†Here, the light projected from behind her and onto the vellem echoes her as an integral part of her process and raises an important question in relation to a long-accepted theory of art. In this instance, is it coincidental that the nap of Smith’s sweater looks remarkably similar to the texture of her painting, Afghanistan, 1963, or is it simply art imitating life? Regardless, the palimpsest technique the artist used to create this image deepens the viewer’s connection to her work and her purpose while inviting further exploration and personal interpretation where the conscious and subconscious can be given free rein.

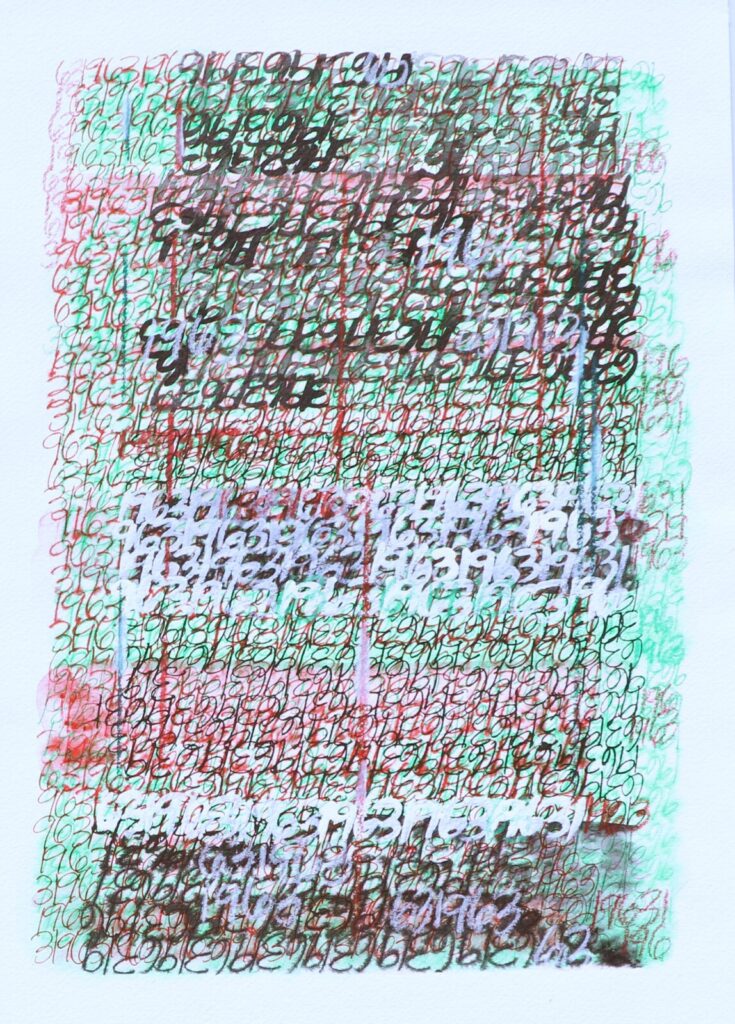

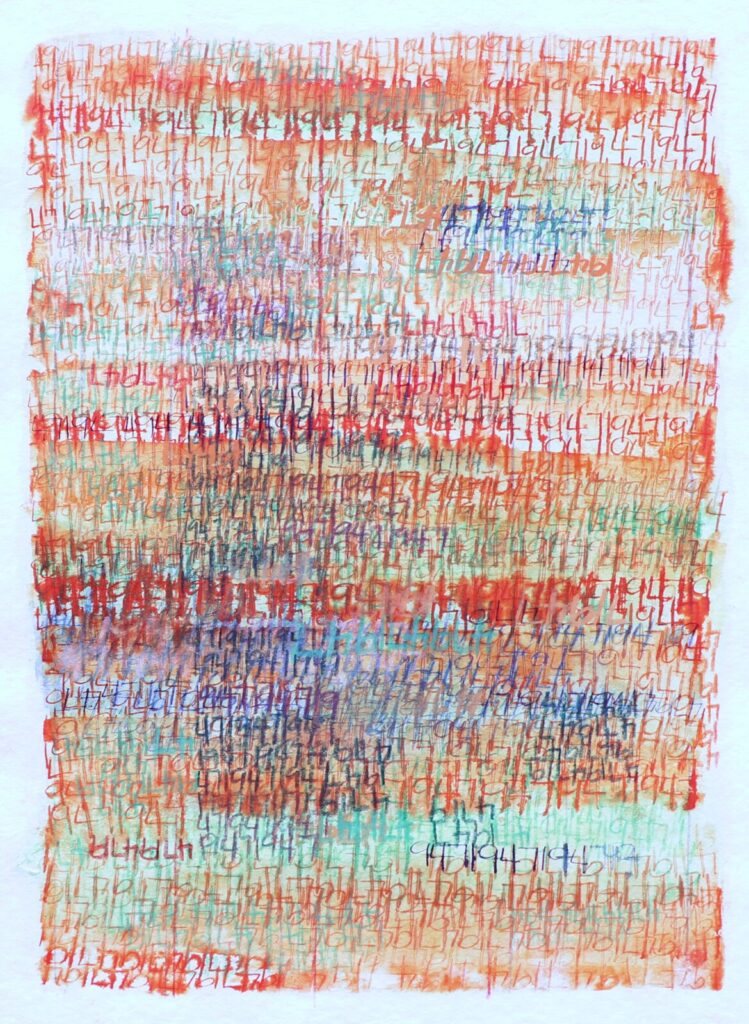

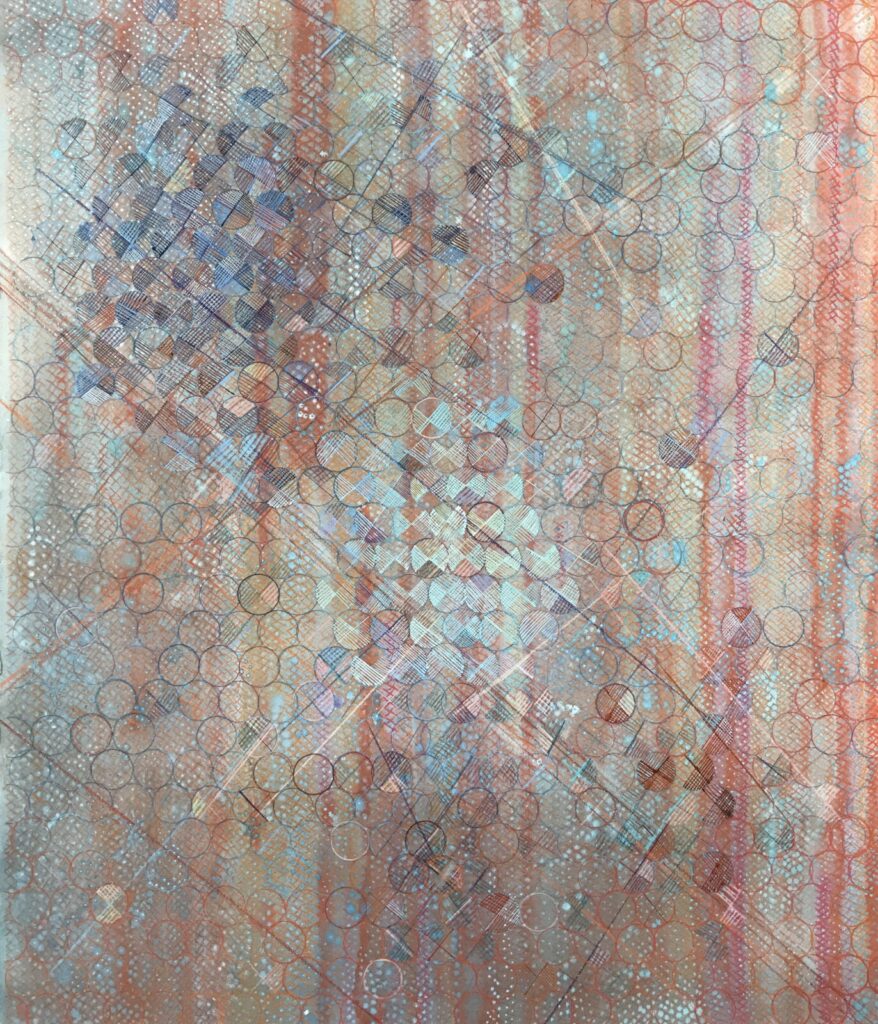

Afghanistan, 1963, and India, 1947 are from Smith’s Suffrage series, which includes the United States, Canada, Italy, and Saudi Arabia, where the date women gained the right to vote became the subject of each piece. These paintings require close examination and are significant because Smith intended for them to represent “both the historical assertion and the absence of female representation in the history of voting rights and political office.†They are literally figurative works that are at the same time abstract and real.

The palimpsest process involves painting the voting rights date on the surface of the paper, then scraping and wiping it away, and then repainting and removing it repeatedly as it builds up the canvas with a rhythmic repetition of color and form that amazes in its singularity of purpose. Smith emphasizes that history is a lot like this where we make marks in the sand and they’re gone the next day: “We still have in our own country voter disenfranchisement with people not getting to vote for any number of reasons, as in our most recent election involving particular populations and the redrawing of districts for political favor. How government is built and policy is made is at the heart of all of this.â€

Things Arise, Things Disappear from Smith’s Accumulation series is also a nod to American history and the ephemeral and transitory nature of time, to the nefariousness and self-serving actions of government, and to the ability of the people (for the sake of freedom and human decency) to endure, persevere, and overcome. The fragments of the American flag I see fluttering in this piece convince me that Smith is acknowledging and drawing on the power of her earlier non-representational abstract work to help advance her goal of creating “more literal content connected to a particular concept.â€

The painting, With Her, makes a substantive statement. Smith places the familiar symbol of the Women’s Movement up front and center—an emblem that combines the astrological symbol of Venus, representing all things feminine, with that of a clenched fist from the 60s and early 70s power movements, particularly black power. The women don “pink†pussyhats with somewhat haunting and almost ghostly visages to the right of the proud nonwhite figure waving the sign. The rays of light emanating from the upper left corner of the painting seem to link the past and present, indicating an uneven and rough journey but one filled with hope. However, I think based on Smith’s broadened interest in intersectionality (a term coined by the African American civil rights advocate and scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989), the content of this painting would have benefited from including a more diverse display of disenfranchised women voters, adding to its effectiveness in communicating the significance of the Women’s March of 2017.

I bring this point up because of the far-reaching comments Smith made as we discussed her personal-is-political views and her ideas related to intersectionality that have her looking toward the future: “The message of the women’s march was intersectional in that you have women in general who faced challenges historically, politically, socially, and personally, as well as other marginalized groups. For feminism to be relevant it needs not to include just women’s rights but human rights. Immigrants, native Americans, blacks, LGBTQI, and individuals with disabilities are all discriminated against in different ways.†Making art that narrates such a multidimensional concept of intersectionality sounds like a monumental commitment, but no more so than the life Smith navigates in order to grow, do her art, and feed her spirit.

To say Smith is a busy woman is an understatement. She obtained her MFA in Painting and Drawing from The Art Institute of Chicago and her BFA from the Maryland Institute, College of Art in Baltimore. She is a founding member and Associate Professor at the Kentucky College of Arts + Design (KyCAD), where she teaches studio art and art history classes. KyCAD became independent from Spaulding University in May 2018 and was approved by the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education to grant a BFA in Studio Art. It is now poised to become the only stand-alone, accredited four-year college of art and design in the state of Kentucky and will have its own downtown campus.

Smith, who is also a certified yoga instructor, lives in the Crescent Hill neighborhood with her husband, two daughters and three cats; and her involvement in the Louisville arts community falls right in line with the guiding principles of her teaching philosophy. So how does she manage all this?

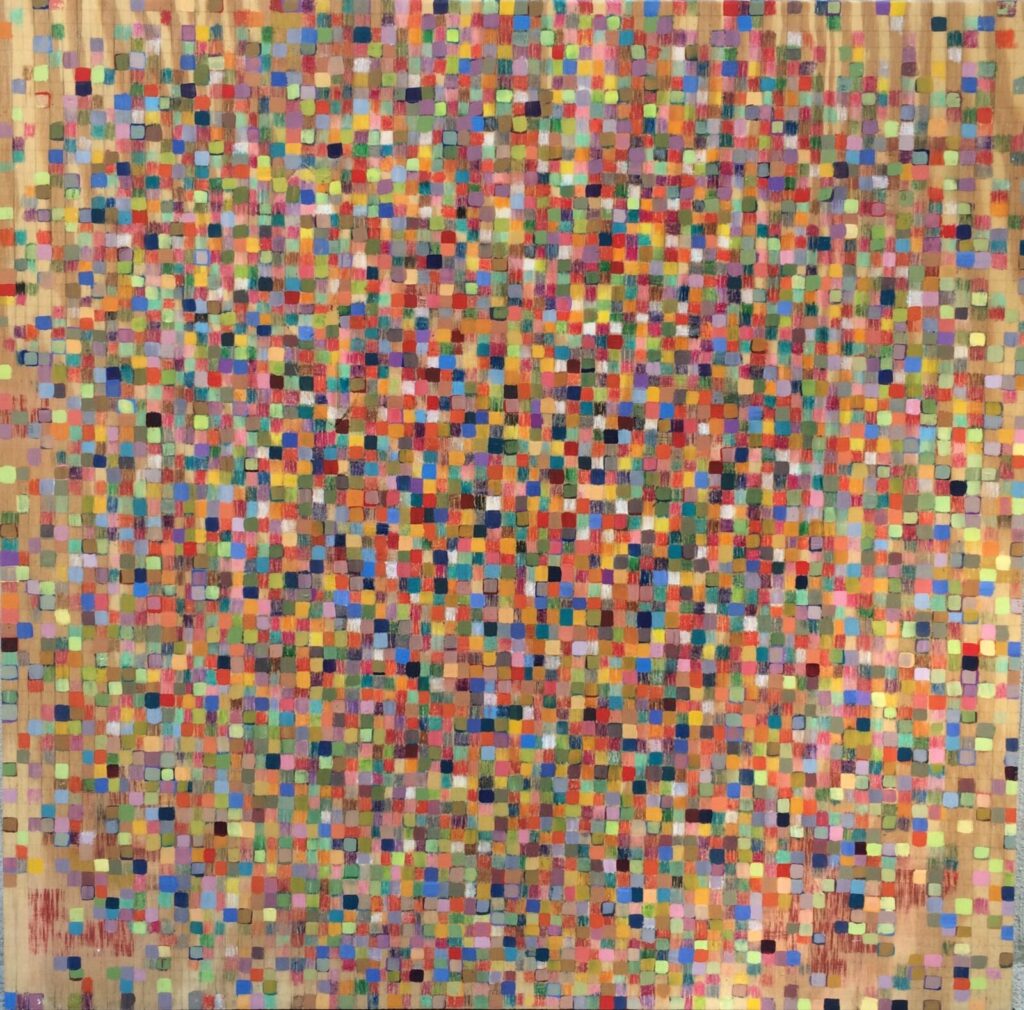

In every artist’s portfolio there is a seminal work that explains a lot and Radiant, But Easy on the Eyes, epitomizes Smith’s process and practice of art—past, present, and future. Beethoven had his Fifth Symphony that served as the bridge from his early Classical style to his later Romantic style, culminating with his Ninth Symphony—his magnum opus. Radiant bridges Smith’s earlier nonrepresentational abstract work in her Accumulation Series with her current realism and narrative approach in Personal Is Still Political and beyond.

Radiant, But Easy on the Eyes vibrates with energy. It looks like a square of irregularly shaped pixels from an enlarged computer image that teases you into thinking it will eventually assume a recognizable form. Instead, these juxtaposed blotches of glowing color seem to rearrange themselves the longer you look at it. Smith attributes the radiance of this piece to the spirituality she explores in her personal life through yoga and meditation and to her process of making art by “using deliberate, repetitive marks in ink and pencil [as she] investigates the tension between the ‘chaos’ of ‘wet’ media (ink) and the ‘order’ of ‘dry’ media (pencil).†These are the moments where she reclaims her “sense of inner peace by connecting to a larger life cycle, and consciously marking the passage of time in ink and pencil†(www.skylarsmith.com). So, for Smith, moving from women’s suffrage in 1913 to the centennial celebration of the 19th Amendment in 2020 represents more than a stitch in time.

Ann Taylor, in an article for The Atlantic (March 1, 2013) honoring the 100th anniversary of the 1913 Women’s Suffrage Parade, recounts the abominable treatment these women received during the march from the men who had deluged Washington, D.C. for President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration to be held the following day. “Marchers were jostled and ridiculed by many in the crowd. Some were tripped, others assaulted. Policemen appeared to be either indifferent to the struggling paraders, or sympathetic to the mob. Before the day was out, one hundred marchers had been hospitalized.â€

Smith with her own inventive tribute, Homemakers’ Rebellion, brings these women into the 21st century wearing pink pussyhats as they march out of and back into the picture, essentially saying, “We are here, we are making progress, and we are not going away!â€

Impressive in her resolve, Smith does not try to emulate other artists although she is notably inspired by the works of three contemporaries: Mark Bradford, an African American artist living in Los Angeles, known for his large abstract grid paintings combined with collage representing aerial views of the city’s segregated neighborhoods; Julie Mehretu, an Ethiopian-born New York City abstract artist who creates politically themed works on a monumental scale by using a variety of techniques and media to layer her canvases; and Japanese artist Yoyai Kusami, who works primarily in sculpture and installations and is currently best known for her Infinity Rooms that provide viewers an unparalleled virtual experience with art.

Smith says she never feels limited by her media or content and, even with her busy schedule, she is looking forward to pushing the art side of herself, never losing sight of her goals and purpose, “Because the narrative for me right now is important, I want my current work to be very audience focused. I’m interested in making art where I am connecting with people in more direct ways, especially in making work that has a political bent to it or effects change so that the conversation doesn’t end right there. The message may be literal but the impact has to go beyond that.â€

Smith’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and she has curated several in and out-of-state exhibitions. She has also been the recipient of grants from The Kentucky Foundation for Women, and Great Meadows Foundation Artist Professional Development Grants.

Edward Hopper, the great 20th century American Realist painter said, “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.†Skylar Smith is committed to making more art and to additional community involvement as the centennial of the 19th Amendment approaches, reminding us that black women (and men) did not get the right to vote until 1965. Facts like this and continued voter disenfranchisement and discrimination drive her artistic narrative.

UnderMain would like to thank The Great Meadows Foundation for support of our 2019 programming, which will include twelve in-depth studio visits of Kentucky artists. See other submissions related to this project: Dr. Emily Elizabeth Goodman on the work of Melissa Vandenberg, and Hunter Kissel on the work of Harry Sanchez, Jr.

The Great Meadows Foundation is a grant giving foundation whose mission is to critically strengthen and support visual art in Kentucky by empowering our community’s artists and other visual arts professionals to research, connect, and participate more actively in the broader contemporary art world.