On a recent trip to New York, I decided to visit the Grey Art Gallery at New York University, located in historic Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The mission of this university gallery is to collect, preserve, study, document, interpret, and exhibit the evidence of human culture.

My mission was simply to check out the exhibition titled “The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal” after reading a review by Roberta Smith in the New York Times. I ended up seeing a second show that made me realize that if we are each to be seen as one of the humans that makes up that culture, we must first be visible.

“The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal”

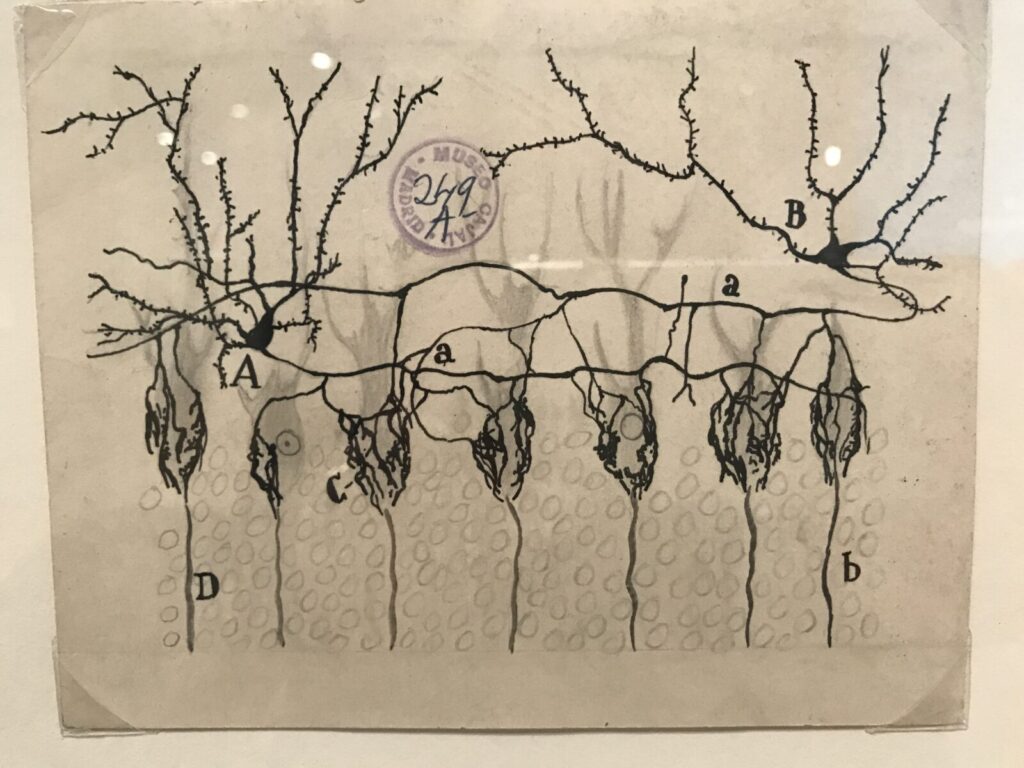

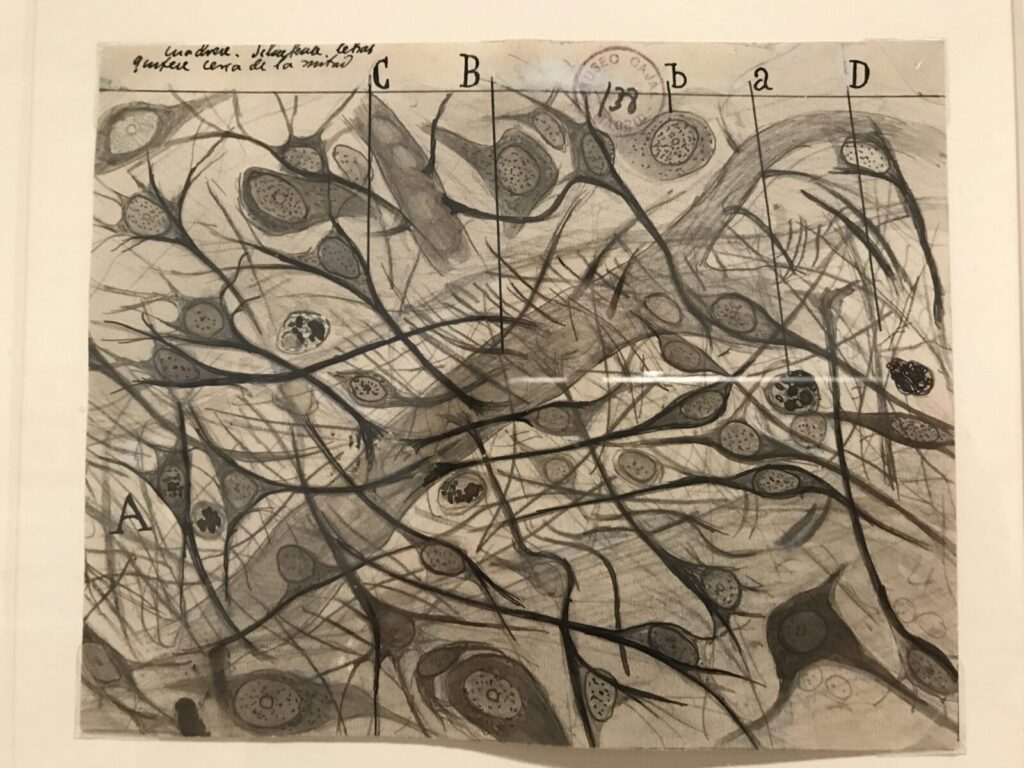

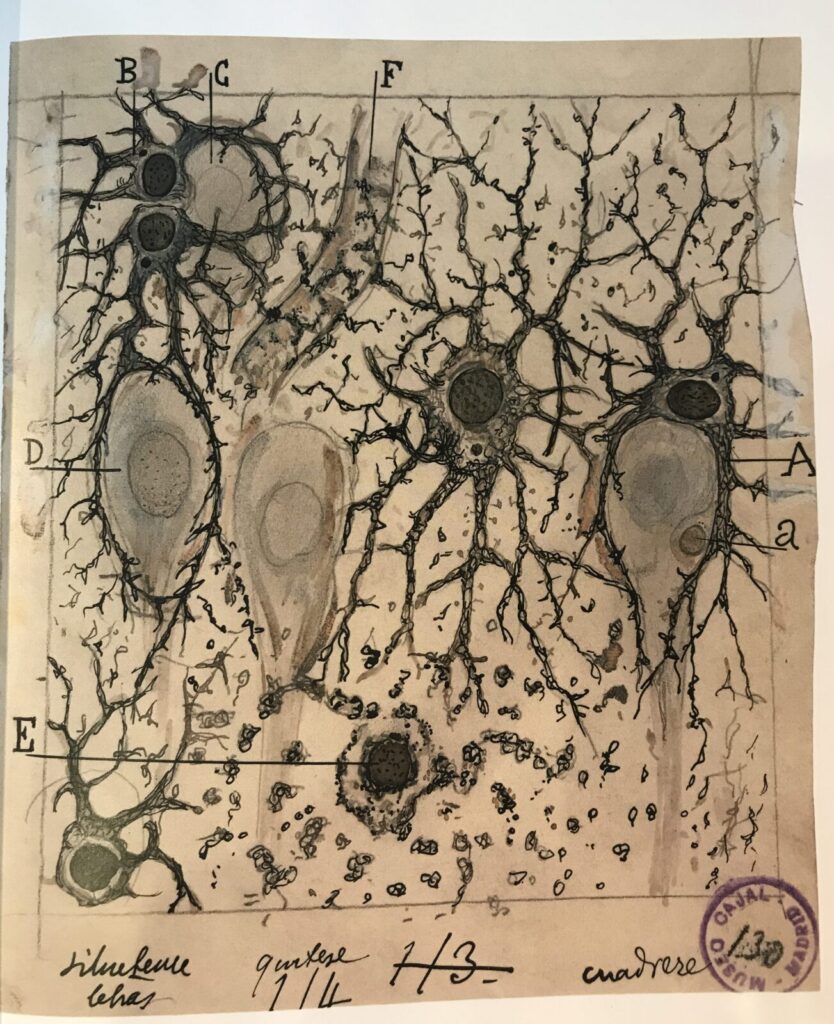

The drawings in this exhibition are small and enormously captivating. Based on microscopic observations of cells, neurons, and gray matter of the brain, they morph into surreal abstractions. The compositions grow into poetic – even tragic – realities with descriptive titles like “pathways mediating the vomiting and coughing reflexes”, “a cut nerve stump of a rabbit six hours after damage” and “neurons in the cerebellum of a drowned man”.

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) is considered the father of modern neuroscience. He was also an artist. Working with a microscope, pen, pencil and paper, he drew these images freehand as a way to evidence his scientific discoveries. As a neuroanatomist working at the turn of the century, his work is equal in stature to Charles Darwin or Louis Pasteur, albeit relatively unknown to the general public.

In 1906 he received The Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his discovery now known as the Neuron Doctrine. As Roberta Smith sees it, Cajal was famous for uncovering the fact that “neurons were in touch, without touching”.

There are more than 80 of Cajal’s drawings in the show, selected from over 2500 drawings, made between 1890 and 1933. Originating at the Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, this show opened in January of 2017, arrived at NYU this year and will remain on view there until March 31, 2018. The following dates then fill out the tour for this traveling show.

- MAY 2, 2018 – JANUARY 1, 2019 | MIT Museum, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

- JANUARY 27 – APRIL 7, 2019 | Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

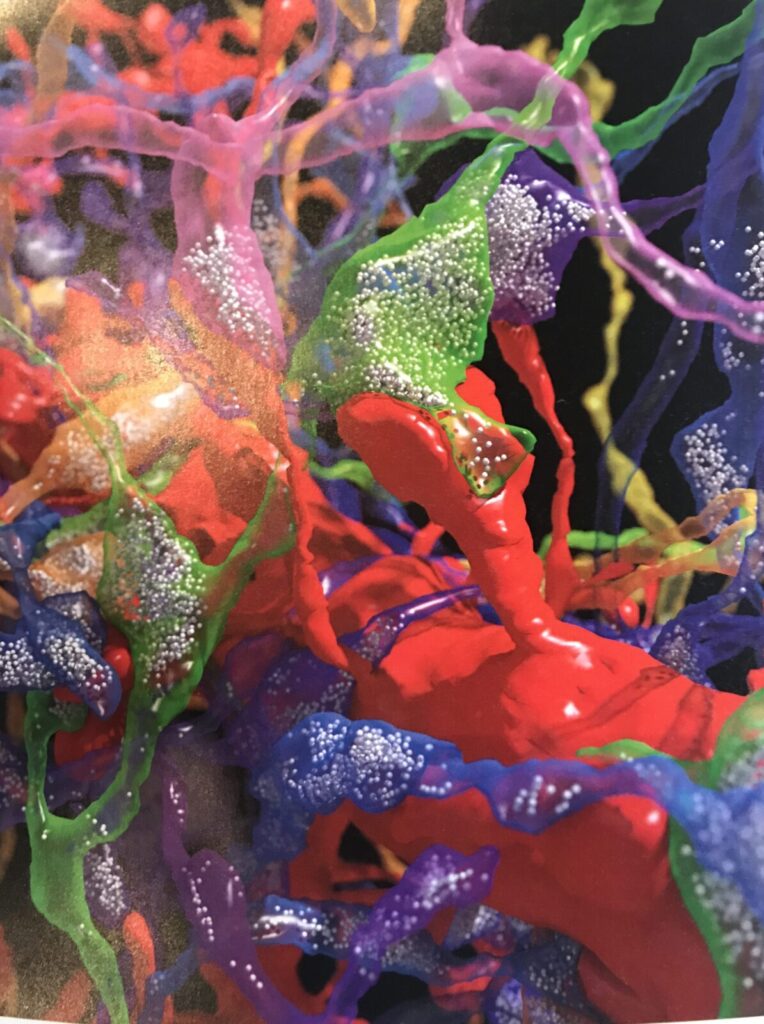

While solely dedicated to Cajal’s work, the show also includes adjacent galleries with more colorful, technology-driven imagery made by neuroscientists working today. These images demonstrate the validity of many of Cajal’s arguments – explained in wall text and in a 207-page catalogue with an essay by Janet M. Dubinsky titled, “Seeing the Beautiful Brain Today”.

In the digital image below, Dubinsky provides evidence of one of Cajal’s foundational arguments. The synaptic vesicles (small white spheres) that release chemical messages at each synapse are shown in the axon branches (transparent colors) surrounding the dendrite. Dubinsky states that:

Synapses strengthen or weaken with practice or disuse, a property that underscores learning at the cellular level. This variability is referred to as synaptic plasticity, an idea Cajal embraced as necessary for mental function

The “Glass Brain Flythrough” demonstrates how information is carried through the brain and was captured by MRI brain scans of the cerebral cortex (gray matter) and bundles of nerve fibers (white matter).

[aesop_video width=”70%” align=”center” src=”vimeo” id=”253047859″ caption=”Glass Brain Flythrough, 2014, Short clip of the animation, Gazzeley Lab and Neuroscape Lab, University of California, San Francisco, with the Swartz Center for Computational Neuroscience, University of California, San Diego, Syntrogi Labs, Matt Omernick, and Oleg Knoings, Lent by Adam Gazzeley” disable_for_mobile=”on” loop=”on” autoplay=”on” controls=”on” viewstart=”on” viewend=”on” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

In an attempt to stimulate a little grey matter, I had visited a few other shows on this trip, including: Auguste Rodin, Michelangelo and David Hockney exhibitions at the Metroplolitan Museum of Art, Carolee Schneemann at MOMA PS1, and Laura Owens and Jimmie Durham at The Whitney Museum of America Art.

For intriguing content that made me want to learn more, “The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal” was on the top of my list, until I decided to take the stairs to the lower level of the Grey Art Gallery.

Baya: A Woman of Algiers

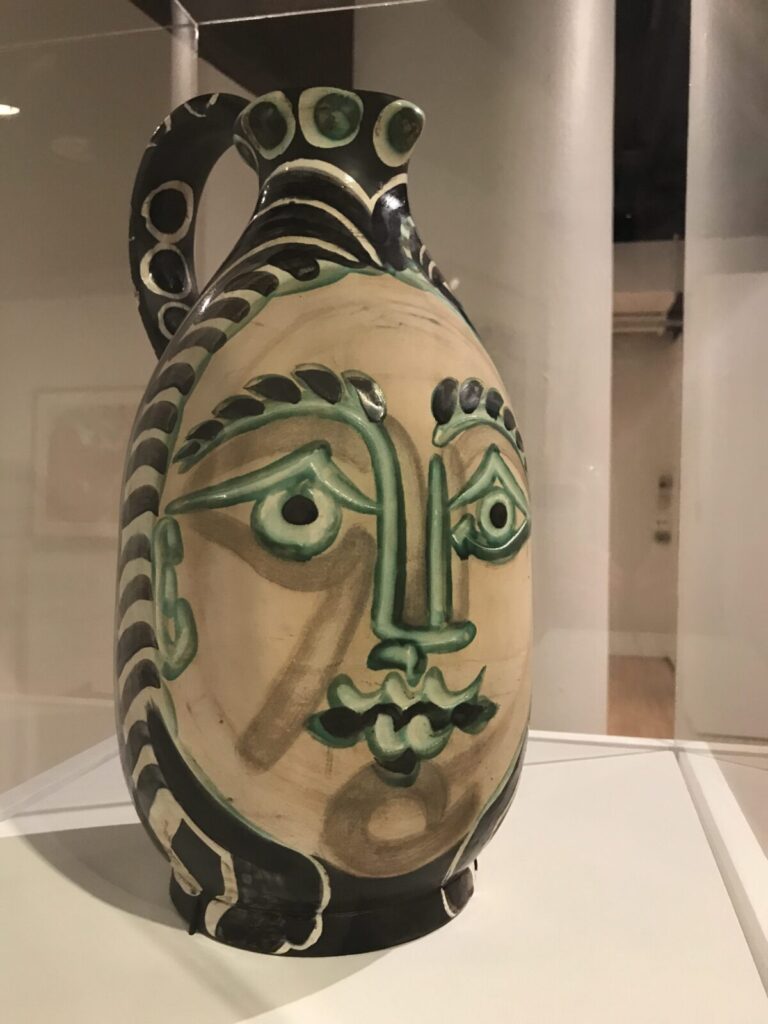

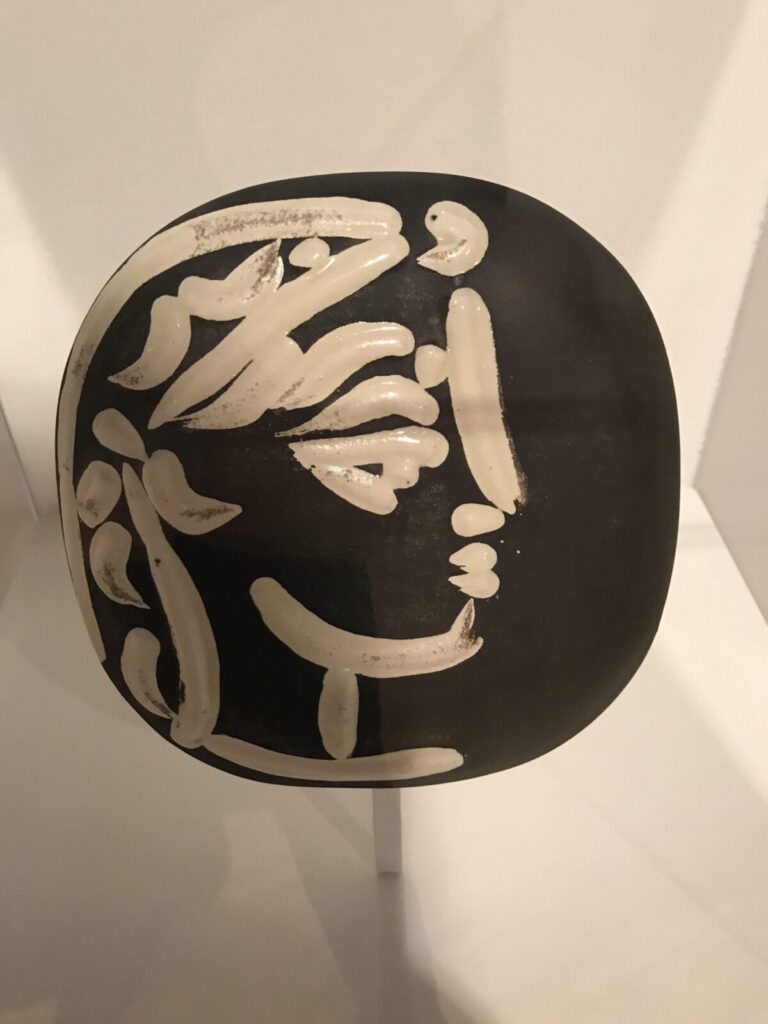

At the bottom of the steps, I found a quiet gallery filled with color and familiar shapes. At first glance, it looked like five or six covered pedestals held Picasso-esque ceramics and on the walls hung vibrant paintings of various women in long dresses with fanciful hats and/or hair.

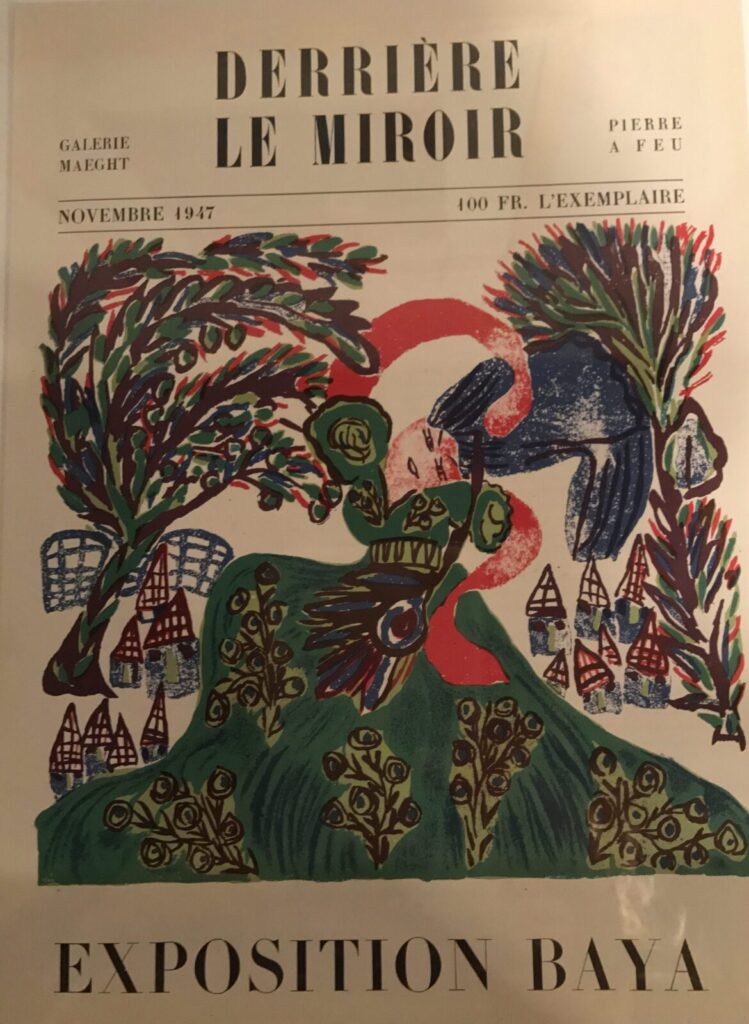

The introductory wall text clearly explained that this exhibition is about Baya Mahieddine (1931-1998), known as Baya, a female artist who was orphaned at age five. An artist who had never been the focus of a solo exhibition in North America until now.

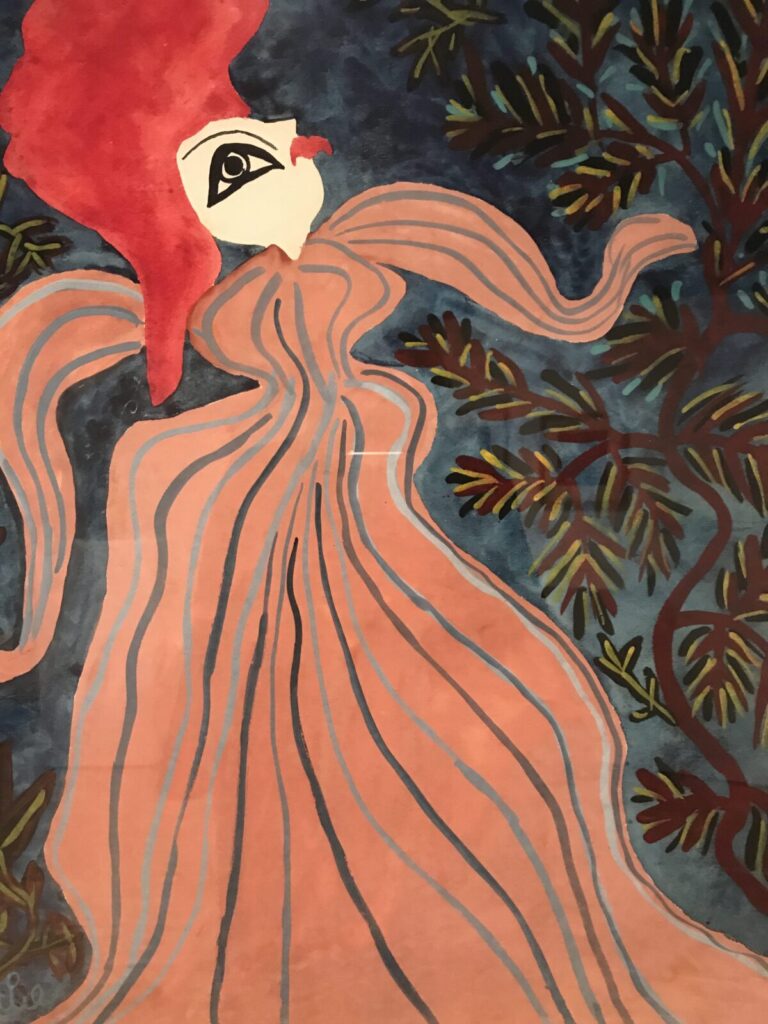

Curated by Natasha Boas and accompanied by a 57-page catalogue that describes Baya as a woman veiled, a woman trapped in traditional roles, marginalized as a painter in her own country of Algiers, a woman who even by her own signature is enigmatic, a one-eyed woman peering out from behind her own multi-cultural identity and the denial of labels like “outsider artist” and “art brut”. A woman who, according to Boas, by seeing, is finally seen.

Boas’ essay, titled “Baya: The Naked Eye” introduces us to Baya, who was “born Fatma Haddad in 1931 outside Bordj el-Kiffan, a Mediterranean beach-town suburb of Algiers, to a small rural tribe of mixed Kabyle and Arab heritage that relied entirely on an oral tradition of storytelling and folklore”.

Later adopted by a French intellectual, she was encouraged as an artist and given access to prominent figures in the art world, including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, André Breton, Jean Dubuffet and Joan Miró. During this time, Baya entered a rare period of recognition for an artist of her training, one that could be viewed, so the curator states, as “Baya stepping into the visible”.

Boas states that, in 1945, Ami̩ Maeght, a prominent French art dealer discovered Baya, and that her work Рcreated largely from her imagination and her dreams from a very young age Рwas subsequently included in the Exposition Internationale du Surr̩alisme in July of 1947.

Due to her success in Paris, she was later invited to an artist-in-residency program at the Madoura ceramic studio in Vallauris in the South of France, where she met Picasso.

From the wall text for “Jacqueline’s Profile” we learn that from 1948 to 1952, Baya spent her summers in the French coastal town of Vallauris working alongside Picasso, who attributed his work in ceramic to her influence. Later, embarking on his seminal “Women of Algiers” series (1954-55), Boas reiterates,

Picasso again cited Baya as his inspiration.

Was it Baya or Baya’s artistic style that influenced Picasso? Why does this show not include the ceramics made by Baya during her time in Vallauris?

In 1953, Baya left France and her adopted mother to return to Algiers. She married a traditional Muslim, who was thirty years her senior, and settled into family life giving birth to six children. According to the curator, Baya did not show work again until 1963 and then exhibited annually until her death in 1998.

From one of the supporting essays in the catalogue it is suggested that this image is self-portrait of the young Baya who, lying down to sleep, contemplates her sad and lonely state as an orphan.

If the date on this painting – and all of the paintings in this show – is accurate, 1947, might not Baya have been thinking something entirely different than about her sad and lonely condition? Was inclusion in the Exposition Internationale and her residency a blue period for this young artist?

Was there something that forced her back to Algiers? Could it have been life as a creative in a male dominated world of art wherein she could be little more than muse? Was she, in fact, lying down to sleep? Why did she return to a life removed from making art? Does this show help us see who Baya really was?

Boas makes a final point that Baya’s paintings could be read as culturally subversive in that they “can look back on modernist art history from today’s vantage point and be seen”. But is that with both eyes wide open or through the single lens of another?

These two exhibitions, Cajal and Baya, are inaugural exhibitions making visible for us a kind of brilliance in the human species and, in doing so, adhere to the mission of the Grey Art Gallery. Both will strengthen your synaptic plasticity and are on view through March 31, 2018.