In a 2005 article in the Chronicle of Higher Education, the artist and educator Laurie Fendrich argued that portraiture was dead in the 21st Century. Fendrich observed that in the western tradition the portrait was a pictorial means of trying to “get at and then hold onto the very soul of a person.†And certainly since late Roman sculpture the human head has been widely considered the supreme embodiment of psychic life. Fendrich notes the loss of faith in that notion, that a face could convey a profound sense of the sitter’s psychological being: “Sigmund Freud, of course, put the lie to that idea, and after him, it was pretty well killed and buried by Michel Foucault. The idea of portraiture as a mirror of the soul could survive neither Freud’s theory of repression (by which people hide who they really are even from themselves) nor Foucault’s later contention that a person’s identity is always historically contingent and continuously in flux.†Â

For Fendrich, “the faces in modern and contemporary portraits lean towards distortion because artists have peered at them through the fractured lens of modern anxiety and uncertainty about what can be known.†Similarly, Ezra Pound bemoaned the loss of classical equipoise: “The age demanded an image / of its accelerated grimace.†We have been served that brilliantly by Francis Bacon, Willem deKooning, Peter Saul, Diane Arbus, Robert Frank and many others.

But literally and figuratively, portraiture has now been revivified. A reappraisal of recent portraits would include giving due to the progenitor, Andy Warhol, the court painter to established and would-be reputations in the late 20th Century. Eliminating the quest for interiority provided profound insights into our age and its obsession with celebrity, and offered an acute awareness of the dichotomy between public and private selves. Ironically, Warhol’s best work negating inner psychological being led to a reaffirmation of the fragile human vulnerability of his subjects. Â

We live in an age in which coming to terms with issues of identity lead to extreme measures. Cary Grant remarked, “Everyone wants to be Cary Grant. Even I want to be Cary Grant.†Seeking to “rid himself of all hypocrisies,†Grant tried yoga, hypnotism and conventional therapies, before turning to LSD. One hundred acid trips later he was finally happy and “got to where I wanted to go.â€

The renewed relevance of portraiture and its role in coming to terms with issues of identity is a repudiation of the abstract enterprise of the 20th Century, and a hallmark of the current urgent call for greater inclusivity in our national art.Â

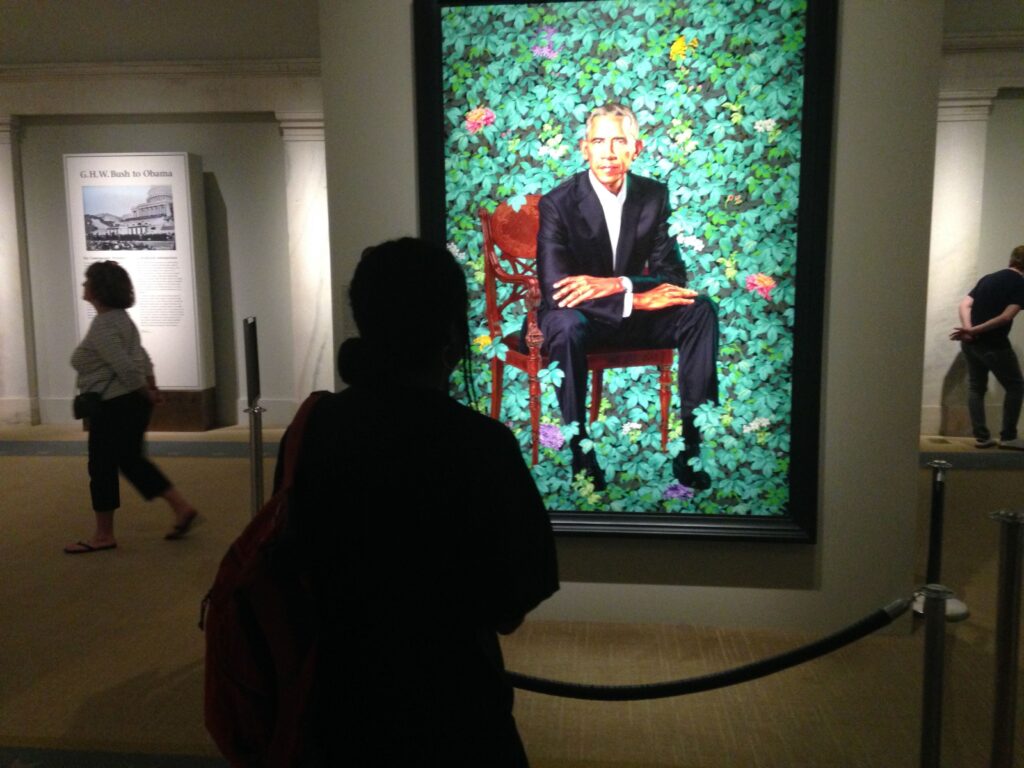

Kehinde Wiley’s Barack Obama is a work that fulfills these new roles, and illuminates and is illuminated by its historical context. And, one might add, by its physical context in the National Portrait Gallery. I had a yearlong fellowship at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which shares the Old Patent Office building with the National Portrait Gallery. Every day I made it my habit to walk to lunch by way of the portrait galleries. I wanted to believe in the heroic stature of the subjects but mostly found it impossible. I did find credible and affecting Winold Reiss’s depiction of the educator and civil rights pioneer Mary Bethune. It is now off-view, a little too Aunt Jemima-ish for contemporary taste. Mary Bethune stood out for many reasons, not least because the Gallery pictures are mostly pale and male.Â

Wiley’s competition of the past 150 years is pretty thin. The only one who might remotely seem like someone to have a beer with is Grover Cleveland (1885-1889 and 1893-1897) by the great Anders Zorn, a Swedish rival to John Singer Sargent. President Cleveland is shown as a comfortably paunchy guy, seemingly open to an informal chat over a couple of PBRs. (Sargent’s great image of Teddy Roosevelt is in the White House, not with the other presidential likenesses.) Norman Rockwell’s Richard Nixon succeeds because it doesn’t aspire to be more than a TIME Magazine cover. He looks wise or devious, depending on your point of view. George H. W. Bush is shown in the White House, as if it were a stand-in for a Houston country club, denoting nothing so much as landed privilege. Bill Clinton, (1993-2001), in a mauvish-blue shirt, has a red Joe Palooka nose, so the artist, Nelson Shanks, gets credit for an honest likeness. That depiction is rotated with a more successful Chuck Close portrait. We see George W. Bush (2001-2009) in a room at Camp David with an odd assortment of furniture somewhat haphazardly shown behind his painfully painted-from-a-photograph, jacket-less, tie-less, good-guy dude smile. It rivals the Shanks Clinton portrait for goofiness.

Kehinde Wiley has mastered and reinvented the rhetoric of the presidential portrait. In doing so, he had a variety of problems to solve:

How do you know it is the past president?

Wiley sits Obama in a White House-ish antique chair (actually invented and not based on a real piece of furniture). The warm brown tones of the chair and its inlay rhyme with the color of the President’s skin, identifying him with the White House. And, duh, of course the painting is also in the American Presidents area of the National Portrait Gallery and was painted for that location. Intriguingly, were the picture not there and the sitter unknown, the authority of the office holder would not at all be apparent.

How does Wiley depict leadership?

Most presidential portraits have direct gazes towards the viewer (an exception – LBJ 1963-1969 peers off into the future). Gravitas and steely resolve have been the coin of the realm for most presidential portraits. In contrast, Wiley shows Obama leaning forward as if listening intently, fully present to his interlocutor. In Leadership in Perilous Times, Doris Kearns Goodwin asserts that the key presidential qualities are humility, acknowledging errors, shouldering blame, learning from mistakes, leadership in perilous times, empathy, resilience, collaboration, connecting with people and controlling unproductive emotions. These are predominantly listening and seeking-counsel practices, so Obama in the guise of someone listening hard signals a shift from older command and control versions of executive authority.

How does Wiley portray the public face of power?

The brilliance of Kehinde Wiley’s solution is to avoid that altogether and to also downplay the parts of the physiognomy that convey emotion, aside from a slight furrowing of Obama’s brow. Instead, we have a self-possessed man with crossed arms, sitting on the edge of a chair. The head and hands are slightly oversized to convey intellect and capacity for action. His body is turned subtly to the right, which helps the sense of projection forward of his full-on gaze. One looks up at the president, whose head is in the upper third of the seven-foot-tall painting. Public concern and private possession are held in balance.

How does Wiley overcome the insipid POTUS style?

No doubt the dullness of the modern business suit is a downer for contemporary portraitists, and presidential settings for portraits are often neutral or corporate boardroom bland. Obama does wear a standard issue, regulation black suit and an open-necked white shirt. Kehinde Wiley’s most brilliant invention is to embed Obama in a bower of flowers that provide a floral biography: African blue lilies reference Kenya, his father’s birthplace; jasmine stands for Hawaii, where Obama himself was born; the official flower of Chicago, chrysanthemums, denote the city where he met his wife and began his political career. The plants engulf him and the chair. Flowers have many symbolic meanings, but their season is spring, traditionally a time of hope and rebirth. The floral background thereby becomes analogous to Shepard Fairey’s 2008 Hope poster. Obama becomes a center of gravity in this insubstantial, floral field. Wiley’s Ingres-like linearity and precise realism lend credibility and a note of authenticity. Meticulous realism – every vein in every leaf – then becomes a stratagem to convey conviction and acuity of vision. In his 1976 book, Escape from Evil, Pulitzer Prize-winning anthropologist Ernest Becker claims that faces and heads “stick out†expressing and exposing individuality. In this painting the floral field has a mitigating effect, so that nature – and perhaps by extension the threat of global warming – share attention with the leader who, like the rest of us, is subject to circumstances beyond our control. In the end, our commonality in the human community is Wiley’s most potent message.