Nudity and nakedness are complicated and often overlapping concepts in the history of art; while historically, nudity has been associated with heroism, virility, divinity, and confidence, and nakedness considered a state of vulnerability, shame, and lasciviousness, contemporary artists have continually blurred the boundaries between these two concepts, leading to new understandings of the bare human form.

In the Lexington Art League’s exhibition, The Nude: Brutal Beauty, now on view at Loudon House, the connotations of both nudity and nakedness—as well as their points of intersection—are on full display, creating a show that questions the historical provenance of nudity in art, as well as our own understanding of nakedness today. Furthermore, building on the dialectic between nudity and nakedness, the works in this exhibition challenge us to consider other diametrically positioned notions, specifically the distinctions of past/present, West/East, human/animal, internal/external, or dead/alive. The result of the exhibition, which spans two floors and contains work by over 20 artists from around the world, is a thorough survey of many of the complex issues that arise when considering the stripped down human form.

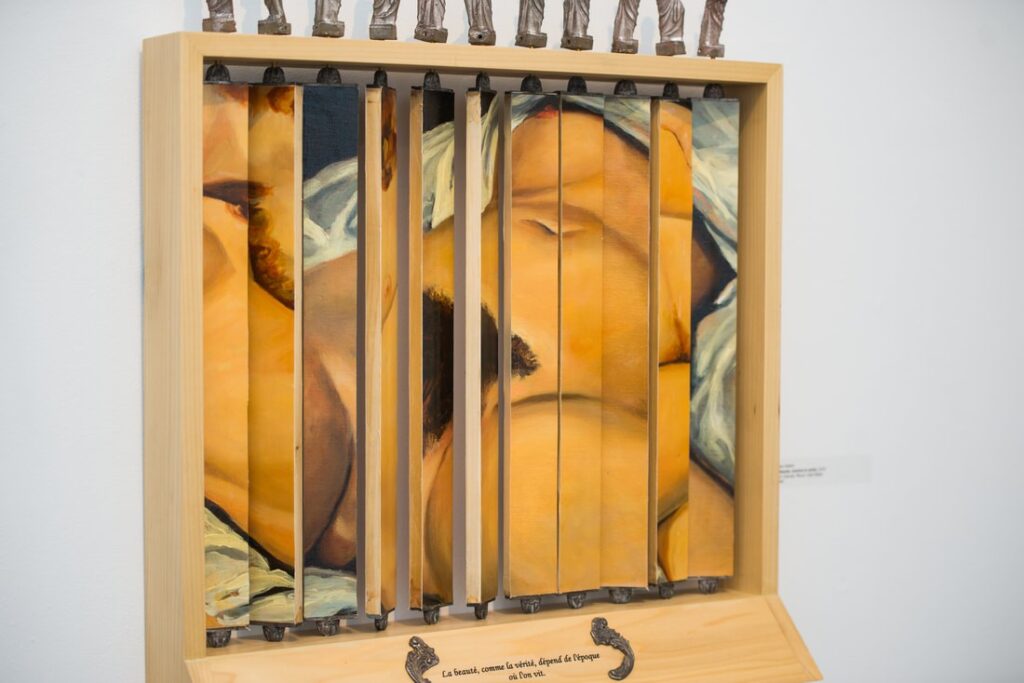

One of the prevalent issues the exhibition examines is how our contemporary understanding of nudity is not only informed by but also challenges that of previous moments. Two artists in particular, James Volkert and Kiana Honarmand, appropriate canonical, art historical portrayals of nudity in order to make comments on the state of the body in art and society more broadly in our current time. For instance, in his piece la beaute, comme la verite: After Courbet, Volkert has appropriated two (in)famous images by 19th century French realist Gustave Courbet, Sleep and L’Origine du Monde, both of which brought scandal upon Parisian society for their frank depiction of women’s sexuality and the sexualized female body. Volkert has placed the works on rotating slats, the handles of which employ another historical nude—the Venus de Milo—and which can be turned to create one of 2048 possible combinations, pointing to the shifting and ever changing conceptions of nudity and nakedness from antiquity to the Victorian era to the present day, a notion further underscored by Volkert’s inclusion of Courbet’s own words: “La beaute, come la verite, depend de l’epoque ou l’on vit†(“Beauty, like truth is relative to the time one livesâ€).

Like Volkert, Honarmand also considers the implications of historical nudes on the present moment, but her appropriation of imagery—largely history paintings from the Italian and Northern Renaissance—involves a more direct intervention on the form in an effort to make an explicit comment on contemporary politics, specifically covering over the naked bodies with lines of Farsi poetry, blocks of color and pattern, and, occasionally, sculptural elements, all of which are derived from traditional Iranian art. The resulting covering of these bodies with this kind of imagery is a direct comment on the programs of censorship and modesty in Honarmand’s native Iran. This gesture also calls into question the role of nudity in both Western and Middle Eastern art and society, both historically and in the present.

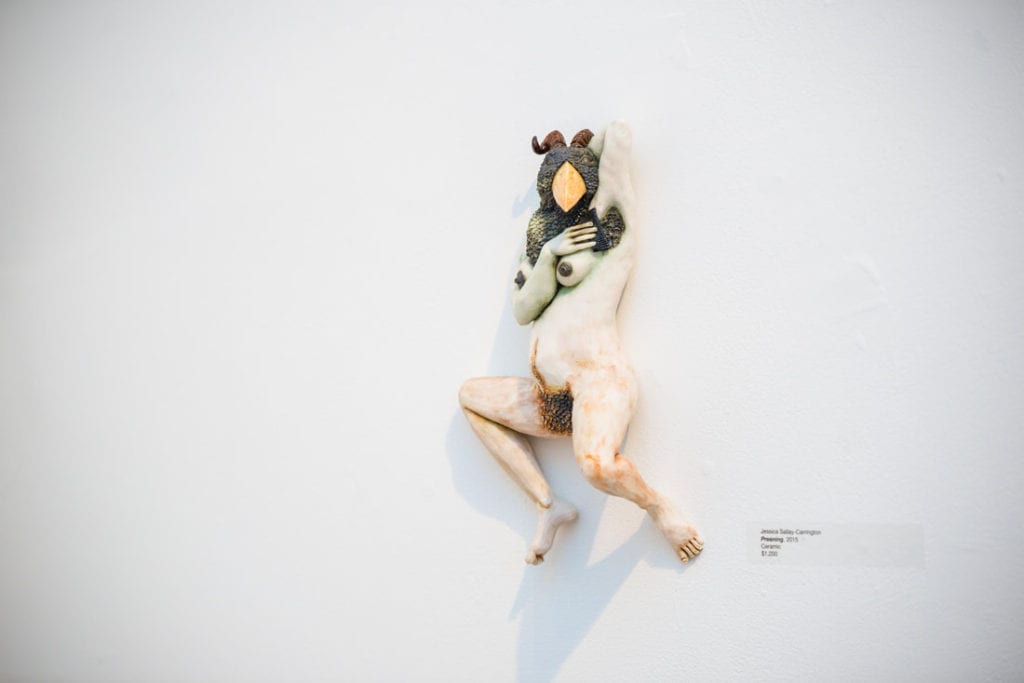

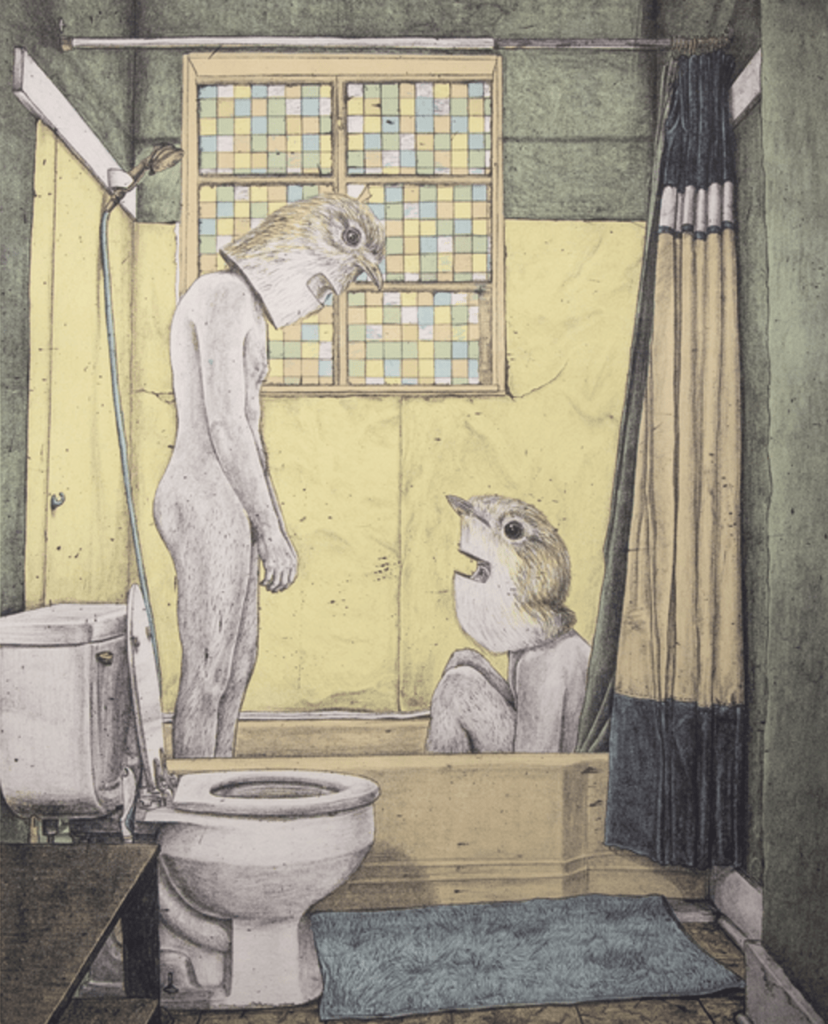

In addition to attending to temporal and geographic dualities with regard to the nude, the exhibition also sheds light on how nakedness is a defining line between humans, the only species to clothe our bodies, and all other animals. For instance, Canadian artist Jessica Sallay-Carrington’s ceramic pieces, Self-Love, Preening, and her serial works Bits and Pieces 1 & 2, involve a hybridization of animal heads—often derived from more than one species, like the rabbit face and ears, lamb’s neck and goat horns in Bits and Pieces 1 & 2—that rest upon a naked human body. Similarly, in his photolithographs, Bathers and Nora, Lexington-based artist Todd Herzberg also juxtaposes bird heads on human bodies, but in these cases, Herzberg makes clear that the hybridity is merely masquerade, as we can see the eyes of each of the humans peering out through a slit in the bird’s neck. In both artists’ works, however, Herzberg and Sallay-Carrington call attention to the limits of associating human nakedness with animal nudity.

At the same time, other artists explore the very human nature of nakedness, looking at nudity and exposure as a fundamental aspect of our shared experience as a species and as a community. In his photographs The Head and The Body I, Jim Allen juxtaposes anatomical imagery—a diagram of the intracranial structures and of the muscles of the torso, respectively—onto the body of an older man. The result is an exposure not just of the nude body, but of the naked structures that lie beneath it, revealing the viscera that is common to all humans. This gesture thus uncovers that nakedness does not stop at the surface level, highlighting the vulnerability that is implicit in both exposing our bodies internally and externally.

Finally, while Allen’s work calls into question the duality between the internal and external forms of the human anatomy, Vinhay Keo’s work Surge from his series Sanctuary/Purgatory considers the dichotomy between the living body and that of the dead. In this image, Keo, whose body has been painted white, appears splayed out in a white cave partially buried within a mound of shredded paper; his head, arms, and one leg emerge from the pile, giving the appearance of a dismembered corpse in the process of decay. The whiteness of his skin evokes the image of bodies covered in lime that have been found in mass graves at the site of numerous atrocities, further underscoring the idea that this body is, in fact, deceased. Yet the position of the body, the tilt of his head and the haphazard placement of the arms, might also suggest that he is not quite dead, but rather has endured “la petite-mortâ€â€”a French euphemism for orgasm—and has fallen back into the embrace of the pile as a result of this ecstasy. This ambiguity thus reveals how nakedness has a connotation of both life and death, especially in considering the body during moments of temporary or complete surrender.

Many other complicated distinctions arise throughout the work within the exhibition, especially when considering the sheer volume of art that it contains. As a survey of the nude in contemporary art, and one that aimed to allow the artists to “present depictions and investigations of their own perspective on the human figure in all its rawness and wonder,†it has certainly succeeded to capture a breadth of different interpretations thereof. The exhibition therefore builds on the long tradition of nudity and nakedness within art history and does so in a way that shows that there are still further avenues to explore even within the most conventional areas of artistic portrayal.

Images provided by the Lexington Art League.