The plurals are not insignificant. The artworks included in Eastern Kentucky University’s current exhibition Truths and Consequences – ending February 15th – deal with the complexities of art’s tendency to work in layers.

This is initially the physical layering of materials and images, and finally the layering of meaning. As juror James Grubola explains the ultimate complexity lies in how these processes of layering contribute the broader concept of Truth. These are not the processes of documentation or the recording of things real or perceived. Instead, they delve deeper into the ways in which artwork is able to create and manipulate reality and how this gives power to depiction. Philosophy or sociology might call this the construction of “consensual reality.â€

Art and media wield an incredible amount of influence in the spoken and unspoken battles waged to establish how we understand our societies and the broader world – and how that understanding translates into larger and much more consequential truths.

Following this tendency towards recognizable depiction, one of the more noticeable threads in the exhibition is figuration. Barring a few painted works, recognizable or semi-recognizable figures dominate, even among the several included sculptures. Of course this isn’t limited to the human figure, rather a host of beings and things that can be readily identified. While this might be attributed to the preference of the juror’s selection and taste, it seems to also follow from the exhibition’s larger theme. This is not the preponderance of truths (again the plural is important) but their consequential effects as well. In the ways that art can make statements about the world, these statements are neither passive nor neutral. Instead they reflect back onto the world and exert a potentially strong influence on how the world is perceived, constructed, and understood.

For example, works like Martin Beck’s Finished During The Eclipse and Barry Motes’ Sibling Rivalry, are weighted with a certain gravity to the choices made in subject matter. Both use people of color as models, one a woman and the other two boys, and temper their depictions with lofty and almost mythological imagery. The history of art and its tendency to silence and make invisible these same people is (intentionally or not) a part of this display. This is one reason why media representation has such a deep and abiding effect on audiences. The figures we see in art, especially when they are people who resemble ourselves, shape our personal and cultural realities. This is most visibly the case with depictions of women, people of color, LGBTQ people and other historically marginalized groups. The ways that art is thought to reflect the world in its broadest sense can also contribute to tangible changes in reality itself. Of the diverse subject matter on display, as well as the diversity of media, there is a shared sense of art’s obligation to representation and its willingness to challenge and experiment in these arenas.

This relates to another theme present in the exhibition – that of the more banal elements of the material world. Devon Horton’s The Swarm, in which a scattered assortment of dumped trash fills the huge canvas, engages with the ability of painting to potentially transform and elevate its subject matter. Or Steven Rasmussen’s In the Ditch, a photographic print that recalls Cindy Sherman’s late eighties series that depicted the filth and decay of food, objects, and even bodies in overbearing color. Stagnant water and a submerged bicycle loom brightly in front of the viewer, the uprightness of the water threatening to also consume the audience. Both of these work against what was once considered appropriate for depiction as art. Histories of beauty or aesthetics are less besmirched than reevaluated, an effect that redefines art’s purpose against a seemingly stodgy or traditional past.

Along similar lines, the exhibition’s other photographic works proved conceptually compelling. In a myriad of ways these engaged directly with the reality of photography and the photographic image. Photographs often play a very privileged role as a mediator of reality. They are taken as reality, as surrogates of the world we see, and as proof of what we cannot or did not witness. But this is quite problematic, especially considering the ability of photographs to be manipulated and used to manipulate. In this way, most of the works included make concept central to their subjects. Two other photographs play considerably with the medium’s outwardly central tenets: focus, and framing.

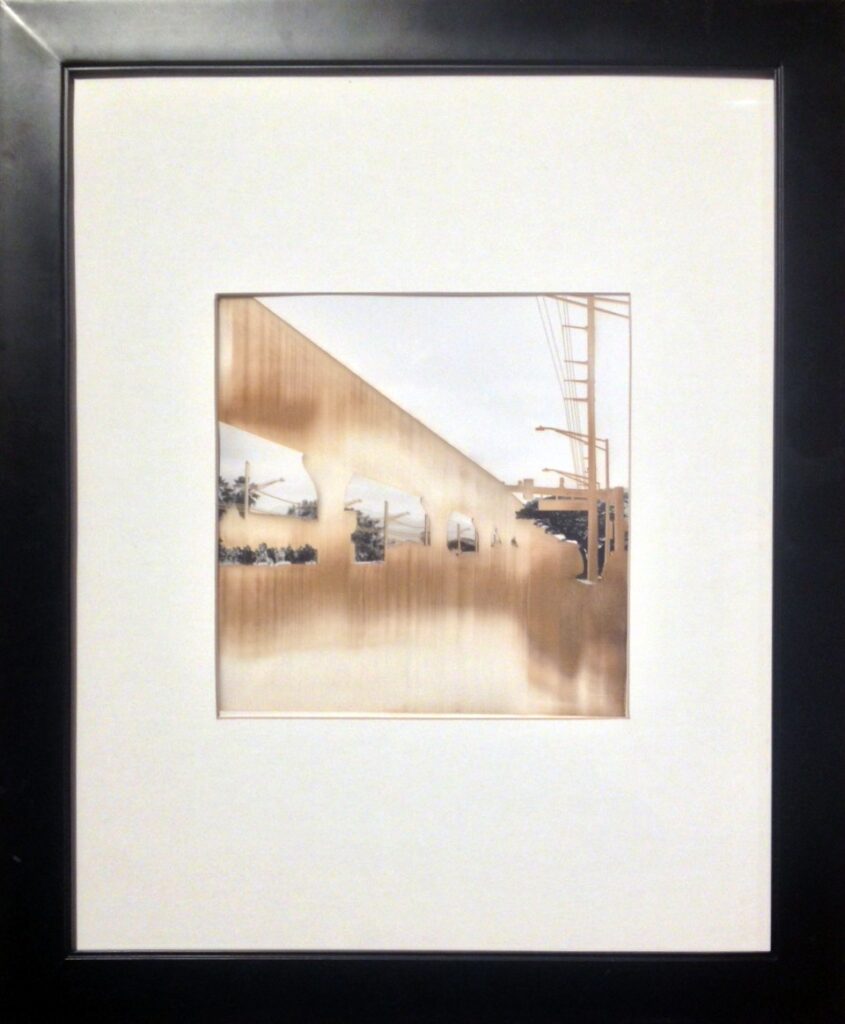

Leah Schretenthaler’s At One Time the Rail Did Not Exist is an image that has been physically and materially edited. The gelatin silver print has had much of its surface removed by laser, making the flattened and burned paper of the print a part of the image. Here a landscape edited by human intervention is reflected by the artist’s own intervention. Similarly, Ian Sexton’s Lightscape 044 pulls the landscape image to the limit of softened color and textured film grain. Landscape is barely perceptible apart from its appearance as melded with the materials of the print. To trace back to idea of layers, there is a sense that both image and object can have a considerable effect on audience perception.

From the minutia of media to the larger concerns of display. I initially found it odd and even distracting that some works (and not all of them) included statements by their respective artists. While these short texts provided context to the works in relation to the theme, they came off as counter to the aims of the exhibition. Yet these sometimes jarring additions ultimately contributed to the conceptual thrust of the collection as a single unit of artwork. Both Art with a capital A and its many individual works take part in the complex dance between what is seen and what is shown. Every single decision, from the choice subject to the media to what the artist might say about his or her own work, to the juror’s selections and the means of display, impacts how this reality is shaped and perceived. Art is not a mirror that reflects the world. Instead, the people and objects we see allow us to discover and make sense of what is ultimately our world.

This exhibition is part of the 2018-19 Chautauqua series at Eastern Kentucky University will explore the theme “Truths and Consequences†through nine lectures by many internationally prominent authors, artists and experts; a special documentary screening.

Joel is a sometimes contributor to UnderMain who always tries to look at things closely. He recently received his Master’s in Art History from the University of Louisiville and has a deep interest in the material realities of photography and other art media, an interest that sometimes comes in handy when taking his own bad pictures.