On August 21st, 2017, I was at Armour’s Hotel in Red Boiling Springs, Tennessee to witness the eclipse. We hotel guests were an eclectic group: a professor of Latin from Notre Dame University; an extended family from Gainesville, Georgia; a gang of young engineers from Baltimore – one of whom wore a superhero cape; Mary Ann from a few counties distant who drank her Zinfandel in a sippy cup to keep out bugs; Frank from Houston who drove a Tesla, my wife – a bourbon historian, and our friends who had chosen this location, a crochet artist and her husband, an oral historian/poet/re-enactor from Springfield, Missouri.

Happily the engineers brought along a high school physics teacher who told us what to look for: the crescent-shaped shadows on the ground that looked like ripples in a stream, sunset on all sides of the horizon, the grayish light akin to looking through a gray camera filter, the ‘diamond effect’ (a gold ring with a brilliant white light at the top), the eerie night light at totality, the sudden appearance of stars and the incredible beauty and precise contours of the waxing and waning sequences, like a celestial Ellsworth Kelly painting in motion. Finally there was the palpable drop in temperature and the uncanny silence of birds as if night had fallen.

Victory Over the Sun: The Poetics and Politics of Eclipse is a riff on some implications of this cosmological event and plays with some of the broader possible meanings of darkness, shadow and light.

Curator Joey Yates defined the parameters of the show:

Artists, who engage in acts of silencing, erasing, covering or masking, as well as conceptual gestures related to eclipsed narratives in American art and culture, will examine themes of blindness, censorship, obscurity and suppression.

The exhibition therefore was mostly tangential to astronomy and more about the subjective ambiguity of perception, erasure and re-inscription, and the uncoupling of common symbols from their traditional signification.

Fibonacci Lunar Activation by Lita Albuquerque is the only work in the exhibition to actually use an image of an eclipse – the black orb hovers above a white perimeter, against a charcoal gray background of an embossed Fibonacci number sequence. Her image has a startling sense of inner light as if the square were internally lit with neon. In her installations in locations as remote as the Antarctic, Albuquerque has interrogated light as the link between earth-bound order and the cosmological order, as well as exploring the tension between the limits of human understanding and the expanse of the universe.

Comparably, Letitia Quesenberry provokes a meditation on the limits of reasoned observation with her wall of five disks asymmetrically placed and internally lit with LED lights that morph across the spectrum (the sequence from blue-violet to violet to red-violet is especially compelling).

The smallest ‘porthole’ is 11 inches in diameter, a medium sized one is 25 inches across and there are three large ones around 39 inches in width but vary as much as four inches. The pulsation of the disks makes it difficult to distinguish between the three large ones because of the compelling illusionism of the concentric bands of color. What in psychophysics is called the JND or “just noticeable difference†is at play: the stimulus magnitudes appear to be the same.

Suggestions that Quesenberry is following in the train of Josef Albers is false: there are no templates and no norms in her art. There are, however, parallels with Eastern European and Latin American art of the 1960s and 1970s. Like the kinetic and op artists of that era, Quesenberry’s use of engineering, science and machined imagery – that is, rational and objective means –are put at the service of a new subjectivity.

Marijke van Warmerdam does a simulacrum of the passage of day and night in Light, her one minute, thirty second video of herself strumming window blinds as if they were a stringed instrument. Sometimes her hand is visible, sometimes not; sometimes she uses her finger, sometimes an open palm; the speed varies. The pleasure of this work lies in the sublime simplicity of her performance with its flashes of light, intimations of concentrated time, and domestic exploration of sensory modalities.

Another group of works in the exhibition focus on processes of removal, just as the eclipse removes sunlight from the day. Censorship as striking out was the subject of several works.

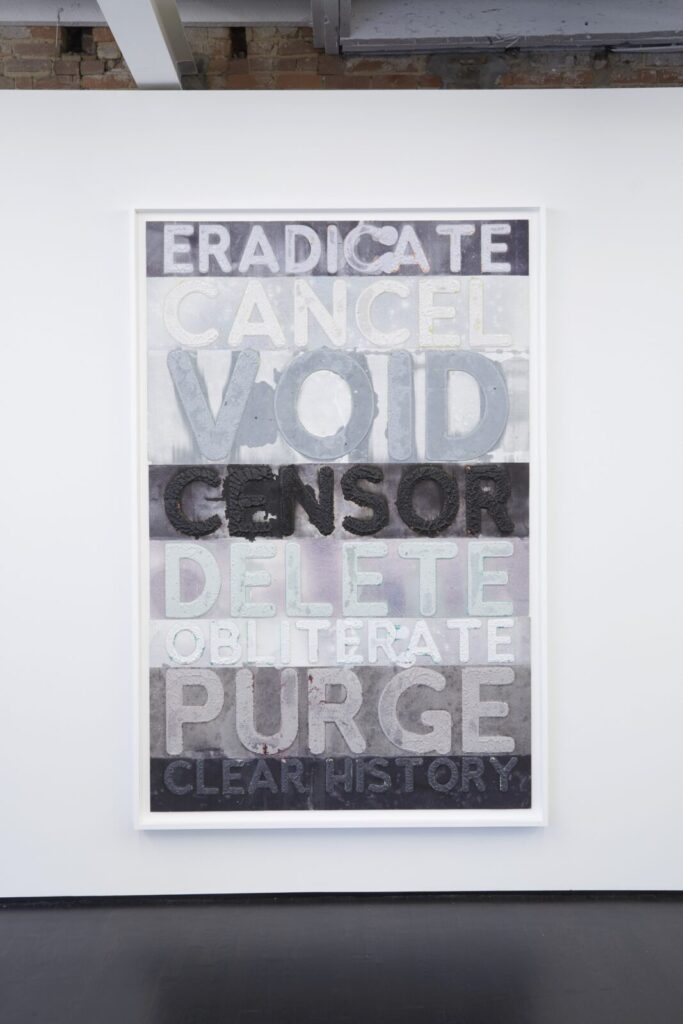

In his monoprint Mel Bochner lists the words ‘eradicate, cancel, void, censor, delete, obliterate, purge,’ and ‘clear history’ in block letters. The mottled and cracked typography conveys a sense of aged materials. The highly tactile letters evoke an urban context, in part because of suggested underpaintings of yellow, orange, green or red beneath the different inscriptions, as if the words themselves covered other, more volatile messages.

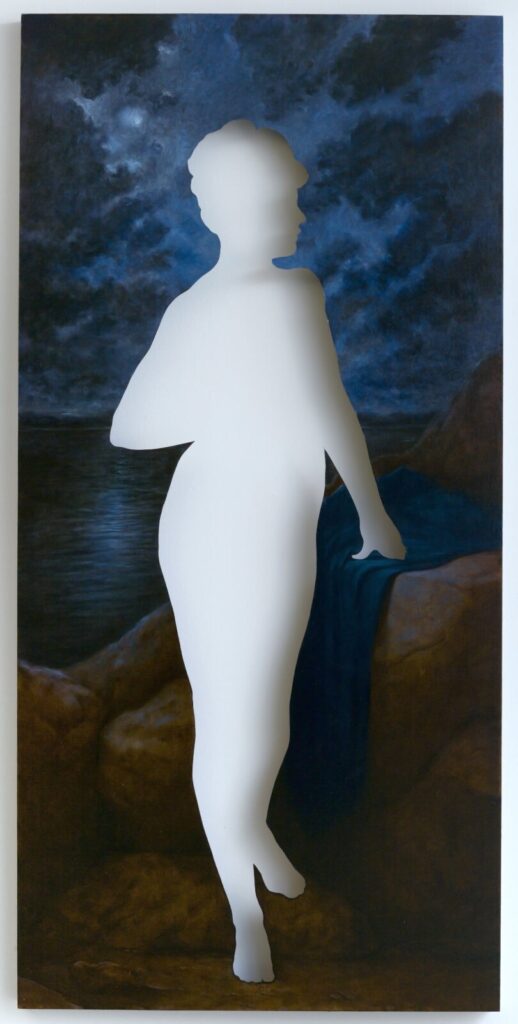

Titus Kaphar’s painting Moonlight cuts out the profile of a Victorian woman in the center of the canvas. Her hand rests on a green cloth as if she had just disrobed. She stands in front of a kitschy landscape, a rocky shore bordering a moonlit sea, beneath an overcast sky. The cut out denies the male gaze its ogle. The empty figure achieves, ironically, a kind of individuality and presence, in part because shifting shadows animate the vacated form against the white wall as one walks past.

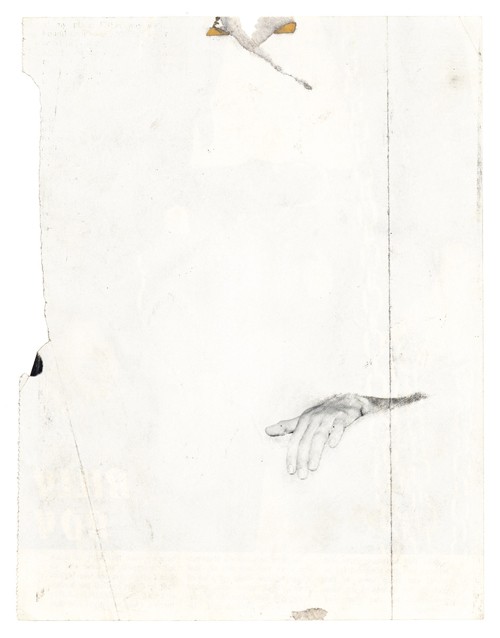

Equally subversive of tradition but more poignant are three drawings by the late Steve Irwin. A hand, two arms embracing an invisible figure, and fragments of a face, shoulder and foot are the subjects. Irwin’s “rubouts†are abraded pages from vintage adult magazines: like the self-taught artist Bill Traylor, Irwin took compositional clues from the condition and edges of the papers he used.

Irwin’s anatomical fragments masterfully transform raw to tender. While most discussion of his work focuses on what he took out from the illustrations using solvents and abrasives, the delicate modeling and colored pencil modulations added to his found material mark Irwin as an extraordinary draftsman.

The popular favorite in the exhibition is Bigert’s and Bergström’s Moments of Silence a fourteen minute assemblage of vintage film and video footage showing a wide cross-section of people from around the globe observing a moment of shared grief. The moment of silence –commemorating and re-communicating with tragedy –is seen in over 20 vignettes.

Men in felt hats from Kyrgyzstan, Kenyan Muslims remembering in sorrow the Nairobi shopping center massacre by Al Shabaab in 2013, Japanese workers in hazmat suits, police and soldiers ceremonially removing hats or helmets, factory workers paused on assembly lines, pedestrians standing in silence at an intersection, taxi drivers stopping and getting out of their cars: the universality of this observation as secular ritual is a confirmation of our commonality. The cuts often provide close-ups of the faces of participants.

Then life goes on: pedestrians cross the street, cars start up again, road workers remount their heavy equipment, soccer players take to the field, and officials sit down again. Small details take on significance, like a green emergency exit sign with a running stick figure above a still, silent group of office workers, or a no-smoking sign beneath a clock.

A second eclipse-inspired exhibition, on view too briefly at UofL’s Cressman Center, was Overshadowed, an intriguing collaboration between Mary Carothers and Brian McClave that utilized slow scan photography to composite thousands of images into a single digital file. Photographers were recruited across the path of totality to record the momentary lack of light: it translated into streaks like the black lines that appeared on leader in old films.

Victory Over the Sun makes as much coherent sense as many other assemblages of diverse work. It brings to a local audience a stellar collection of international artists juxtaposed with work by local and regional practitioners.

KMAC provides an excellent free take-away pamphlet which re-prints the extensive wall texts and illustrates at least one work by each artist. I might have preferred a more narrow focus, but then I would have missed some works in this excellent selection. Bigert and Bergström’s Moment of Silence comes closest to my memory of sharing awe at a transcendent celestial event.

On view now through December 3rd at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft, 715 West Main Street, Louisville, KY, 40202, KMACmuseum.org, free admission.