“The things that are close to you are the things that you can photograph the best. And unless you photograph what you love, you’re not going to make good art.†– Sally Mann

“Maybe [in the series] Immediate Family, it was a love that was too hard to express, so she took pictures.†– Jessie Mann, Sally Mann’s daughter

Rachael Banks is an artist and a tenured Professor of Photography at Northern Kentucky University. Her work deals with trauma, death, crime, and nature as central to her family and upbringing in the mid-South. We met in March 2022 on a very windy, warm day in Cincinnati to talk about her work, chaotic families, safety, self-mending, over-analyzing, and how glad we were just to be alive.

Ely Maris: A lot of your projects don’t have end dates. They’re like open questions. Which are you actively working on now and how do the different series relate to each other?

Rachael Banks: At the core of all the different projects I’m working on, everything goes back to this idea of generational trauma, but also memory – memories we inherit and how that influences who we are as people.

RB: Between Home and Here used to be just one project. I started it in my last year of grad school in Texas. It was a reason to go back to Kentucky, because I was homesick. I’ve always been the caretaker of my family and with the first installment of the project, The Passage, I went back home and saw that everything was going on fine without me. So there was this realization – do they really need me as much as I think they do? Is there a part of me that needs them too?

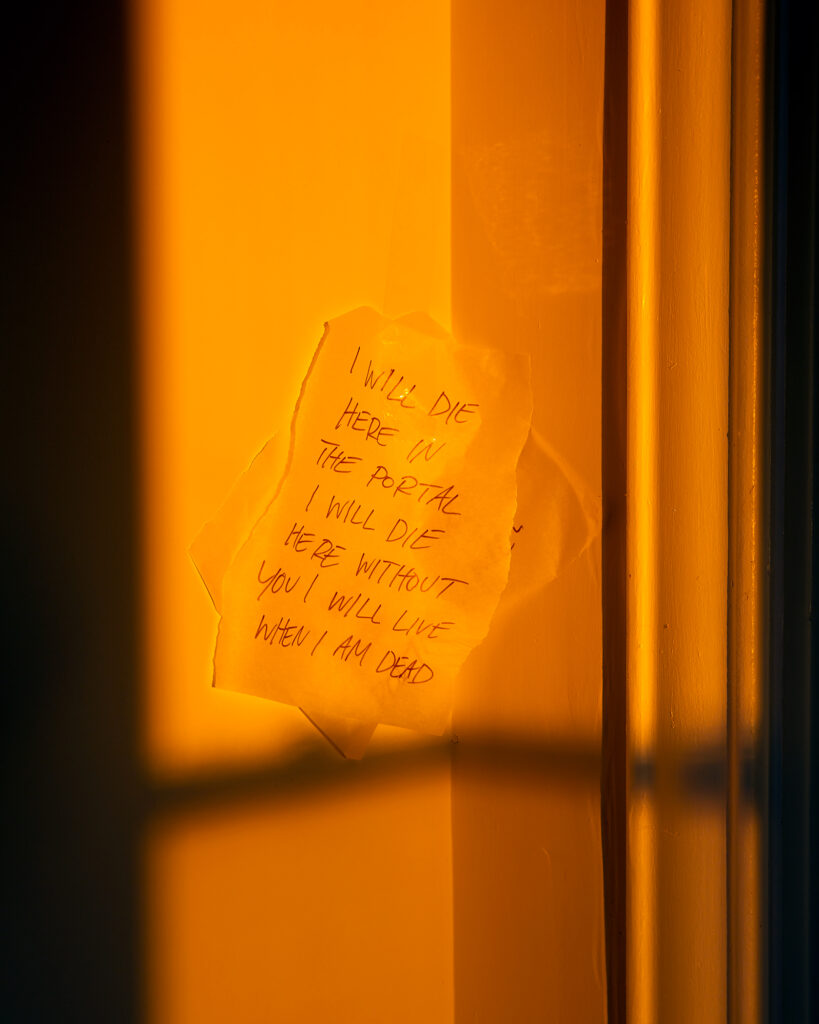

RB: The second installment, The Return, is when I moved back. It felt like a weird in-between – trying to maintain this new, healthier version of myself, but also getting sucked into bad things. And the third chapter, The Mouth, is what I’m working on now. I’m still looking at my family, but I’m thinking on the scale of generations and how trauma, addiction, and mental health issues are passed on. My brother and sister are who I make work with the most, and my sister has two kids now, which is terrifying. So that project is, okay, how are we all going to turn out?

EM: Are they comfortable with being such a big part of your work?

RB: My brother doesn’t like it, but we had a conversation years ago where he said he felt like it was the only thing he could give me, so he does it because he knows it’s important to me.

EM: And what about Immediate Danger? I saw on your website that it required a password. I tried “..please?†but that didn’t work.

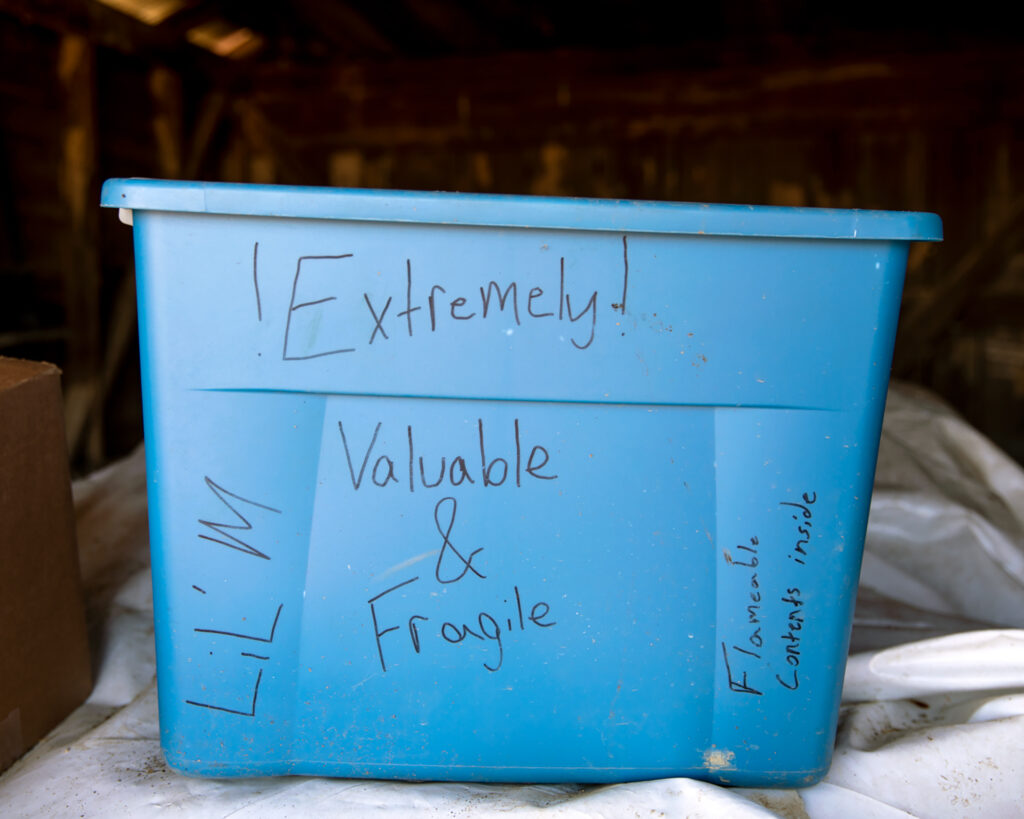

RB: So Immediate Danger is about crime and me thinking about what is dangerous – what looks dangerous but actually isn’t, or what doesn’t look dangerous but totally is. I think there are problems with who we define as being “dangerous.†My brother and I look identical. And, on the surface, my brother is someone who can be seen as dangerous, but in my experience with him, he’s the most gentle person I know. If anyone is dangerous, I think it’s me, because I have the ability to take narratives about people and control them and share them. I feel dangerous too because I’m a chameleon. I’m able to conceal parts of myself that are “bad” and my brother is more, hey this is me and doesn’t hide anything. My brother has been through a lot but there’s nothing about him that’s hateful and I envy that because I feel like I am full of hate and he’s just not. As he’s gotten older, he mirrors my dad in a lot of ways, who was incarcerated for part of my childhood and struggled with alcoholism. And it feels like, it doesn’t matter how straight you try to stay the path, there’s this predetermined fate.

EM: Like an undertow? Forces working on you that you aren’t even aware of.

RB: Yeah, you are what you are and it comes out at some point. Immediate Danger is also a subchapter of Like a Bad Penny – the idea that bad things repeat themselves. For all the things I try to avoid, I am attracted to people that also have these fucked-up backgrounds. They are the only people I can have relationships with, it’s like this shared understanding of trauma, vices, and bad habits. The other project I’m working on is kind of related to family, but also…deer. Deer come up a lot.

EM: Yeah, portraiture is very dominant in your work, but the series Fawn seems to be getting more into landscape. Does it feel like a departure?

RB: Well, I think generational trauma can also be geographical. In the Sally Mann documentary What Remains, she talks about this incident where an inmate escaped from jail and the police chased him onto her land and then shot and killed him.

EM: Of course that would happen to Sally Mann.

RB: I know, right?? So she talks about going to the spot where he was killed and seeing this little pool of blood that remains and watching the ground absorb it. The way she talks about it is beautiful. And then she went and made Body Farm.

So there are deer all around my house. At the height of the pandemic, I started photographing them because I had nothing to do. I became fixated because I couldn’t photograph my family. I would put food out but if I even left my front door, they would run off. I couldn’t get close to them. I thought: These aren’t portraits. I don’t know what I’m doing. This has nothing to do with the work I am making. But the more I was making it I was like…fuck, it does.

RB: A doe had twin fawns during the summer and this felt like a good omen. But COVID was going on, and I was thinking of death and mortality, so I also thought will they make it? One morning I see one of the fawns, laying down near the street. I go and grab my camera. I walk toward the fawn. It looks at me but doesn’t move. I get closer, and it’s still not moving and I think something must be wrong. So I get to it and realize it’s been hit by a car. Its legs are broken, its bones protruding, but it’s just laying there, totally calm, probably in shock. I can’t even save it, there’s nothing I can do. I get a towel to wrap it up and move it into my yard. I’m photographing it. It feels weird…I hate that I’m doing it, but I think it might be important later. I reluctantly called the cops. They came over and shot it in my yard, took it, and all that was left was a spot of blood. Things die, animals die, but it felt really symbolic. Since that fawn has died, I’ve watched the other deer grow older and they come into my yard now. Before I came to meet you, they were all in my yard waiting for me to feed them.

EM: Personal iconography feels really important in your work. Certain symbols repeat, like the deer, not just in Fawn but in other series too…like you’re building up an arsenal of symbols, like it’s something protective.

RB: Personal iconography is really important to me because it’s the thread that keeps everything connected. There are other connotations with the deer. My dad hunts, so I have very distinct childhood memories of us watching deer together. When my dad went to jail, one of the only things he kept in his cell was the Fawn Beanie Baby (this was the 90s). We both had one. I didn’t see him from age 8 to 12, so as a kid, whenever I saw a deer, it felt like a good omen. Then there’s this term “fawning†a lot of children of alcoholics develop – the need to please people. I relate to that a lot. So Fawn is a story about a family of deer but at some point the story gets tangled with my family story. I know this is a lot…I’m like Charlie…

EM: Charlie! With the red string, trying to make everything connect…that is my north star meme. I understand completely. It’s like, you have all this hurt, all this chaos, and you have to put order to it, make sense of it in your own way.

RB: I have this compulsion to make images because I don’t want to forget anything. But I also want to be able to look back and say you made it through that. No one appointed me to this role but I see myself as the family archivist.

EM: I have a similar family history and feel very connected with how you approach photographing your family. There’s this complex distance you have to keep to be safe, or keep them safe, but you also want to commune with them, understand why they do what they do. Perhaps to a fault. I have a sort of anti-tenderness toward my family, which is a word that kept coming up for me when looking at your work: anti-tender.

RB: I’m so happy you say that. You are one of two people to say that about my work. There’s a little bit of distance that is protective. I’m very close to my family but I’m also an outsider. I’ve always been sort of isolated. I have this camera that is a physical barrier. But at the same time there’s something about the camera that makes them open up a little more. There’s this distraction that makes it easier to get things out of them. I think my family is very supportive but I don’t know if they always get it, but I also don’t know if they care. I know that they trust me. The fact that they don’t really care tells me that they trust me.

EM: Even though you’re working with your family and close friends, almost none of the photographs are in domestic spaces.

RB: Yeah, right, they’re never inside.

EM: Maybe that’s part of this refusal to be too tender, too intimate.

RB: We’re kind of feral. I grew up in the suburbs of Louisville but my dad lives on a farm now, so when we’re all together we’re always outside. And around all his animals. Animals are reoccurring too. Someone asked me once if I was an animal photographer and I was like oh my god, am I an animal photographer?? But everyone in my family has always had a lot of animals. I can’t filter them out. Animals are also kind of a coping mechanism. I photograph my black dogs a lot, which is my play off “the black sheep.†In folklore, black dogs are also seen as guardians.

EM: Do you feel pressure to add narrative or context to your photographs?

RB: All my images are tiny stories. And the big picture is this family tree. There’s no way for me to tell everyone exactly what the work is about. I wouldn’t want that. But I do at least want people to see things as visually connected. Many photographers have made work about family, but I also know that my specific experience and what I see are unique to me.

EM: I feel like sometimes artists refuse to acknowledge an audience. They don’t make work with an audience in mind and it drives me a little nuts. I think that can be reckless.

RB: It would be very irresponsible of me to do that, because I am putting my family out there, it’s not just me in the work. Their participation is completely hinged upon their trust of me.

EM: There are things at stake, and acknowledging an audience forces you to ask yourself what is at stake.

RB: Right. The people I photograph are my family first, not just subjects or props. Sometimes I have to check myself on that. When I first started making this work, I was so self-absorbed and destructive and I ruminated in trauma and made work to respond to that.

EM: Like poking the wound?

RB: Yeah, I just wanted to rub it in. I couldn’t move on from it and in that early work I was very abrasive. I wasn’t really thinking how to grow from it or use it in a way that was constructive, it was more look at what you’ve done to me. Now when I make work, I am a friend and family member first. Being able to get to that point required first understanding who I was as a person, and getting sober was a big part of that.

EM: Do you think you could have come to this understanding of your family without taking these photographs?

RB: I would be lying if I said I could have gotten to the point I’m at now without making that work. I think being an artist allows me to think about those things in a constructive way – things I would have found a way to avoid. I’m not a therapy person…I’m not saying “art is my therapy,†because it’s not. Sometimes it’s something I don’t want to deal with, because I am a pretty private person and in my work so much of myself is revealed. So, I need to keep some areas of my life completely under wraps. But it does force me to think about things in a way that I didn’t before.

EM: And how does teaching intersect with your work?

RB: Growing up, school changed my life in a really positive way. Teachers always made me feel safe and I want to be someone that makes people feel safe. I always want to send the ladder back down and this is my way to do that. I also don’t want to be sucked into the narrow void of my own life experiences. Teaching keeps me in touch with what’s going on and it keeps me in touch with my practice. I also don’t ever want to rely on my art to make money. I want to make it at my own pace. I don’t want to force anything…I can’t see myself doing anything else and I’m just glad I didn’t end up in the ground.

Top Image: A color photograph of two people sitting next to each other at a wooden picnic table in an intimate embrace. A field with trees and grass is in the background. © Rachael Banks. Image courtesy of the artist.

UnderMain: On the Road sends writers out of Kentucky to explore the visual arts in cities of the Midwest and near South. This program is generously supported by the Great Meadows Foundation.