Chicago’s Newberry Library is hosting the illuminating exhibition “Chicago Avant-Garde: Five Women Ahead of Their Time.” Curated by Liesl Olson, the Newberry’s Director of Chicago Studies, the exhibition foregrounds the vital institutions, communities, and artistic practices that five women built and the way they shaped Chicago’s vanguard arts scene between the wars. The exhibition focuses on the work of (and connections between) the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks, choreographer Ruth Page, anthropologist and dancer Katherine Dunham, gallerist and curator Katherine Kuh, and the sociable bohemian painter Gertrude Abercrombie. Rather than simply highlighting each’s artistic output (which would be an impressive display in its own right), the exhibition puts each woman’s work in the larger context of their lives – particularly the barriers they faced as related to gender and racial discrimination – and how their practices transgressed and overcame these barriers. Through the use of letters, ephemera, videos, and photographs, the exhibition seeks a definition of “avant-garde” beyond style or technique; the notion of “the vanguard” is presented through the far more expansive and socially engaged lens of the radical choices these women made to further the discipline within which they worked. For instance, Brooks voiced the lives of the predominantly Black neighborhoods of the South Side in her books A Street in Bronzeville and In the Mecca. Kuh opened a gallery during the Depression showing European modern art and later transformed the Art Institute of Chicago’s education program. Dunham’s pioneering choreography inspired the “Dunham Technique” in contemporary dance. But to enumerate all of their accomplishments would be to miss the point, for their vision was not concerned with conspicuous achievements, but in building impactful artistic communities outside of the exclusionary mainstream. As Olsen says, this exhibition “is quietly provocative; it assumes that Chicago had an avant-garde and that that avant-garde was mostly women.”

The exhibition is introduced by a map of Chicago with color-coded lines for each woman that point to their homes, haunts, and other notable gathering locales such as the Arts Club of Chicago. This instructive guidepost helps ground those unfamiliar with the geography of the city and de-centralizes the myth that art happened mostly on the North Side or in venerable institutions downtown. The map also starts to draw the implied connections between each woman’s life, their practice, and how their individual risk-taking served other artists. Though each worked in different fields, Brooks, Page, Dunham, Kuh, and Abercrombie were connected by threads both obvious and subtle. Dunham starred in Page’s 1933 staging of La Guiablesse, featuring the first interracial ballet ensemble. Kuh’s eponymous gallery sold paintings to Dunham by little-exhibited Black artists such as Charles Sebree. Abercrombie held Sunday salons that hosted many of the city’s creative visionaries, and Page’s studio was in the same building as Kuh’s gallery.

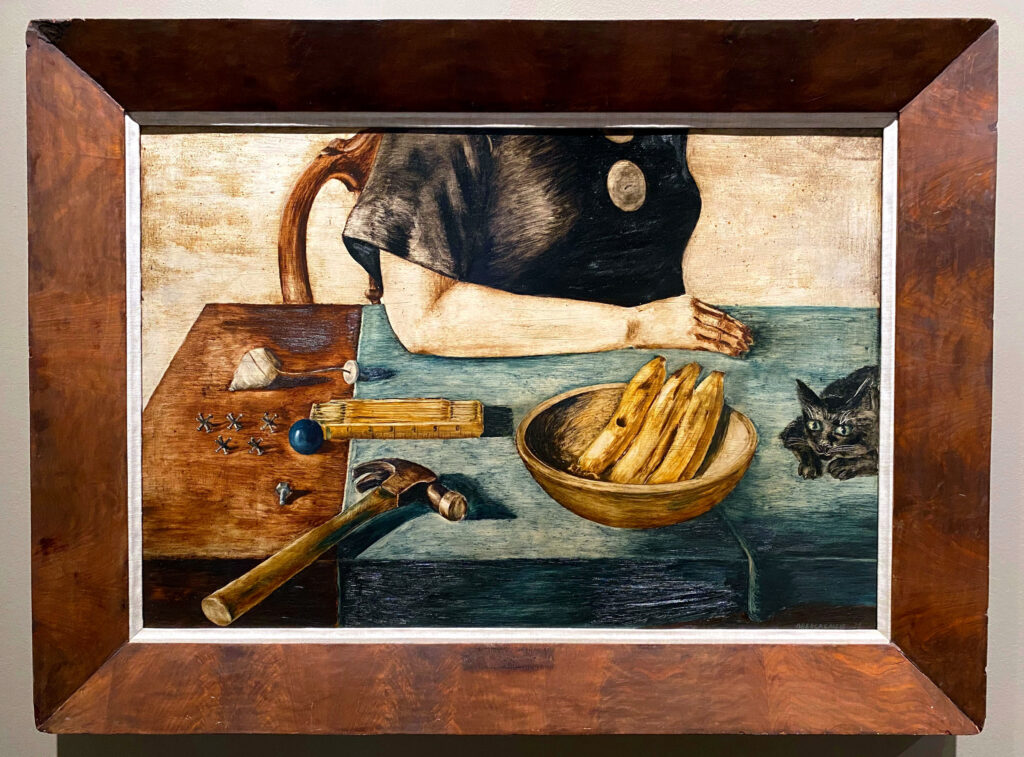

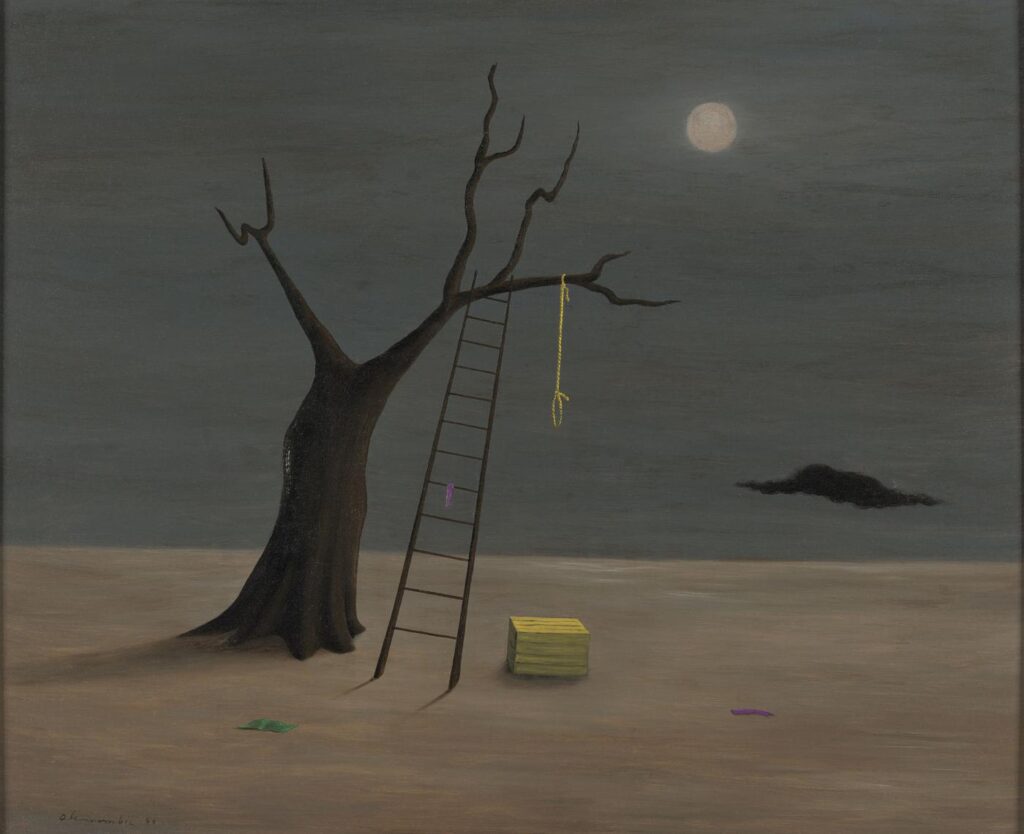

While this sort of imprecise “atmospheric” narrative can be challenging to capture in an exhibition, the Newberry does a fantastic job illustrating the overlapping social and artistic concerns of these five women. An especially poignant example of this is the connection between works that were created in response to racial violence; documentation of Dunham’s ballet Southland depicts the horrors of lynching during the Jim Crow era. Abercrombie’s ominous Strange Fruit (later named Charlie Parker’s Favorite Painting, who was close friends with Abercrombie) depicts a rope hanging from one of her signature barren trees in a flat, desolate landscape. Across the gallery hangs a banner with an excerpt from Brooks’ poem “The Ballad of Pearl May Lee,” which tells the story of a Black man who is lynched for sleeping with a white woman. “Chicago Avant-Garde” sensitively handles these challenging and violent works, placing them in the larger context of each woman’s commitment to social and political engagement, not just as it pertained to race and gender, but also to housing discrimination, harassment from the city’s elite (and conservative) tastemakers, and a culture that disallowed freedom of sexual expression.

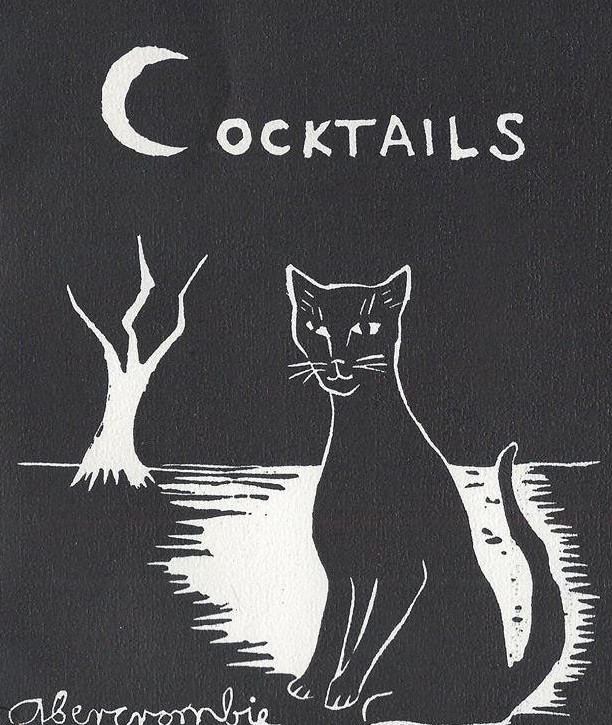

Despite the substantial barriers these women faced, the exhibition leaves plenty of room for celebration. Videos of Dunham performing Haiti (1936), L’Ag’Ya (1938) and Batucada (1943) show her inventive fusion of classical ballet and dances of the African diaspora (especially of the Caribbean, where Dunham did anthropological research as part of her studies at the University of Chicago). A trio of magnetic, brooding self-portraits by Abercrombie – far lesser-shown than her surreal, symbolist landscapes – enliven the entrance to the exhibition. A handprinted invitation to a cocktail party hints at what Abercrombie’s daughter Dinah calls her “gay and radiant…happy and expansive” presence, which is often obscured by her moody and cryptic paintings.

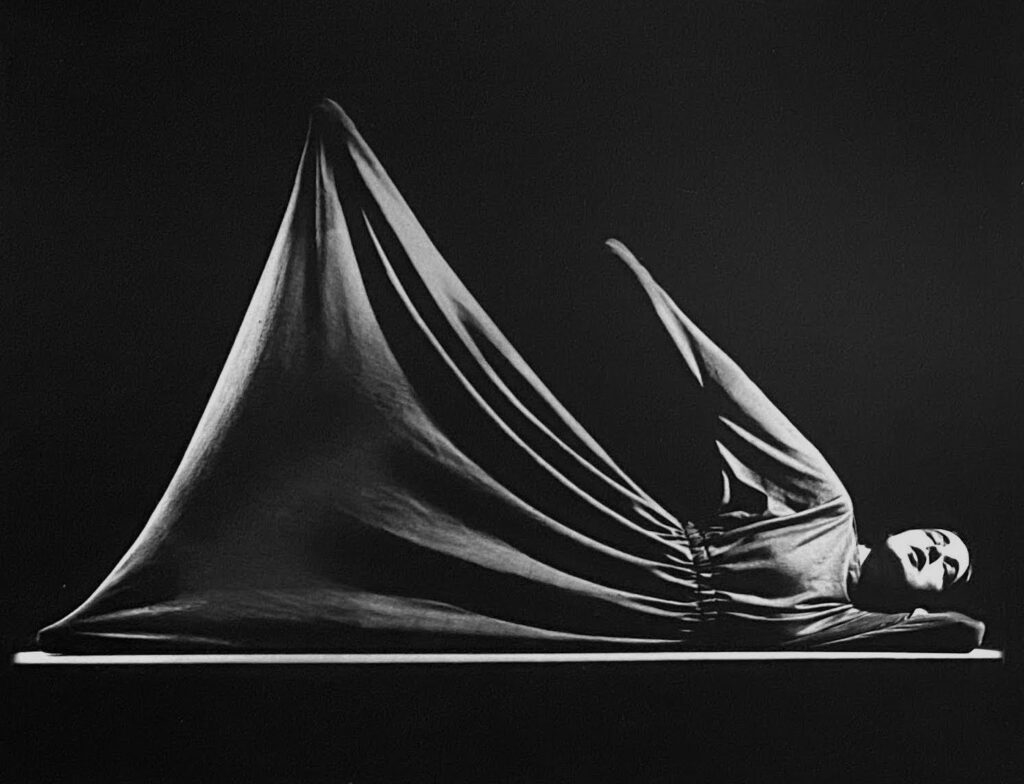

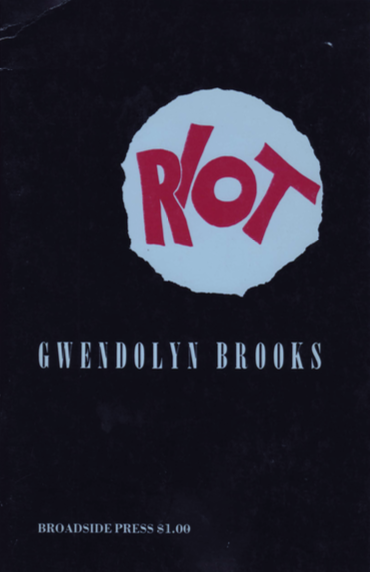

An unpublished essay by Page recounting her love life (simply titled: “SEX”) helps articulate and contextualize the ecstatic movements she attempts in her choreography – movements that are restricted in Expanding Universe by an enclosed body sack and controlled by tape-bound arms and legs in Variations on Euclid. A portrait of Kuh painted by Will Barnet, Homage to Léger with K.K., shows her as a formidable person, able to stand out against the muscular modernism of Léger, whose work Kuh championed and showed at her gallery. The display of Brooks’ 1969 book Riot marks her radical departure from the prominent publishing house Harper & Row to the small, Black-owned Broadside Press in Detroit at the height of her career – showing that Brooks was a woman who lived the values of self-determination and community-responsibility her work espoused.

Presenting an exhibition that is structured largely around biography and its attendant ephemera is a great challenge and one that institutions larger and more robustly funded than Newberry Library often mismanage. Major institutions still struggle to balance an artist’s biography with more erudite discussions of aesthetics and historical narratives, especially when it comes to artists who have been marginalized in the grand overtures of art history. Either too much of a fuss is made over an artist’s life events that it can overshadow the art (as in the focus on Georgia O’Keeffe’s wardrobe at the Brooklyn Museum in 2017), or the impacts of artists’ personal life on their work is overlooked (see: “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction” at the MoMA in 2017, which was stunning but lacked a critical interior dialogue).

Art institutions are catching up to the inflection point that mainstream culture has already reached – one that demands re-prioritizing the stories and contributions of historically oppressed people (as big ships take a bit longer to right). The Newberry Library, which also houses the Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies, has recently had exhibitions on voting rights, revolutionary politics in Latin America, and bike tours of public monuments in Chicago. Even though it is a private research library, the Newberry has long been committed to serving a broader social, humanist program. “Chicago Avant-Garde” flourishes within this ethos, along with being visually engaging and thematically exciting.

The only few clunky notes of the exhibition come in framing a few of the works in relation to other, more famous personas. This is seen in the focus on Page’s brief (but impactful) affair and collaboration with Isamu Noguchi, who designed the costume for Expanding Universe, and the anecdotal, one-time meeting of Gertrude Stein and Gertrude Abercrombie in 1934. Both instances seem to attempt to put Page and Abercrombie into conversation with the international avant-garde movements of the era (Abercrombie even sometimes referred to herself as “the other Gertrude”), but these connections wrestle attention away from ones that might be more interesting. In all other ways the exhibition succeeds; the language is accessible, not didactic, the pacing is thoughtful, not rushed, and the overall design tips more in the direction of education than entertainment (a trap of many contemporary exhibitions), but never at the sake of enjoyment.

The real delight of this show cannot be observed on its walls, in its cases, or even heard in its excellent digital companion experience. Just as these five women knew then, the real impact of the work done by the Newberry will be seen in the future exhibitions and dialogues that “Chicago Avant-Garde” invites and inspires. Back in 2018 and 2019, many talking heads in the art world were eager to proclaim it the “Year of Women” for art institutions, with many prominent women artists receiving overdue major exhibitions (Joan Mitchell, Dorothea Tanning, and Anni Albers, to mention just a few). In a time when most art institutions’ collections, acquisitions, and exhibitions are made up of 10-15% women artists, there is a great danger in proclaiming any sort of “arrival.” This disparity will take decades to course-correct, but until then the art world should look to exhibitions like this: not ones that attempt to validate women artists within the shadow of an inflexible canon, but exhibitions that actively rebel against it.

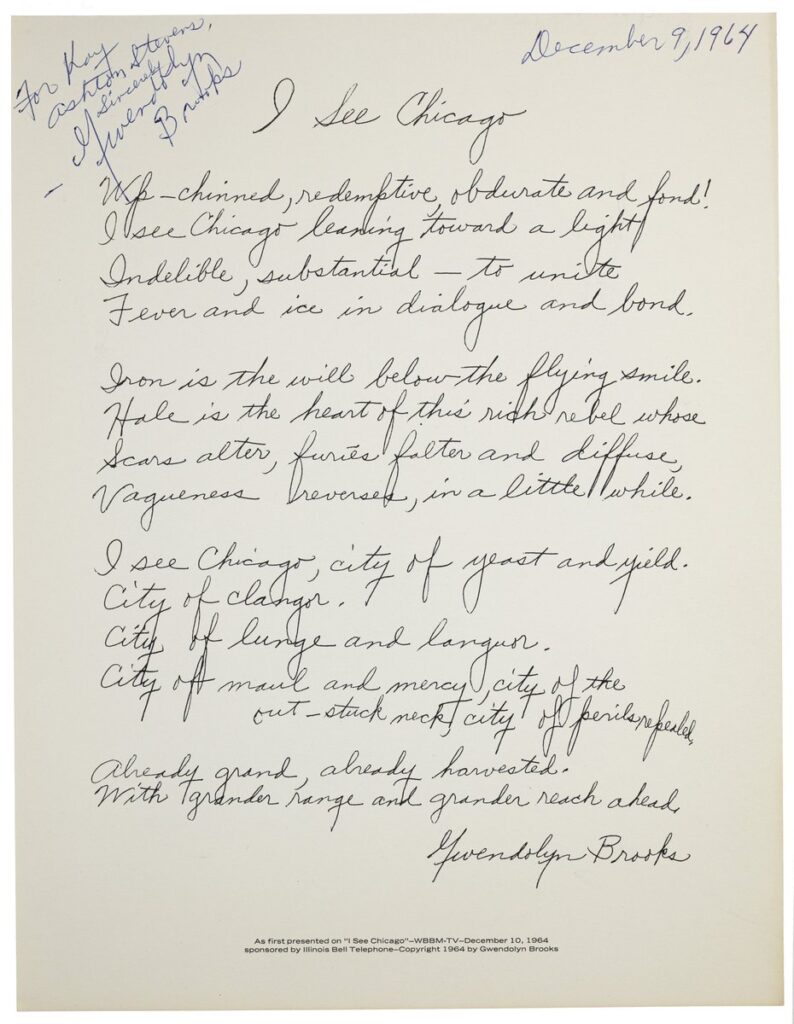

Chicago was the home of and crucible for many radical modernist women, a fact that is often muscled aside by the city’s more visible outputs of steel, skyscrapers, and “broad shoulders.” In a displayed handwritten copy of her poem “I See Chicago,” Brooks recasts Chicago as a “city of yeast and yield. City of clangor. City of lunge and languor. City of maul and mercy, city of the out-stuck neck.”

In 1935, Poetry magazine published a short poem by Harriet Monroe, a poet and editor who founded the Chicago publication in 1912 to provide a platform for avant-garde poets (Poetry is still active and is housed in an illustrious cultural center, The Poetry Foundation, just three blocks south of Newberry Library). Monroe’s poem honored the recently deceased Jane Addams, a hugely important social reformer in Chicago. While neither of these women is featured in “Chicago Avant-Garde,” both would fit right in. That is the problem inherent in any exhibition, even one as successful as this one: you can never give due to all those who would deserve it. In Monroe’s poem, Addams and her influence are eulogized but not entombed:

“I have done my work,” she said in dying,

Ah, woman immortal, whose rest is won,

Today the world’s grief is replying,

Such work as yours is never done.

Bravely you made a grand beginning –

The torch you lit is still aflame;

The game you staked has many an inning,

And those you led will play the game.

– Harriet Monroe, Poetry, July 1935

“Chicago Avant-Garde: Five Women Ahead of Their Time” is on view through December 30, 2021, at Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St, Chicago, IL 60610. Explore more at www.newberry.org.