Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) is the first of three venues for the sprawling Barbara Kruger survey, THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU. Kruger is one of the most recognizable and influential contemporary artists – not just in the art world, but in visual culture. For four decades, she has been critiquing the structures of authority, identity and desire, adopting the very images, words and strategies used by those in power to barb her attacks against them. THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU brings together a wide range of works by Kruger, including her iconoclastic collages from the 1980s, video and audio works from the past thirty years, site-specific interventions and installations throughout the museum and city, and “Replays†of previous works that have been animated and updated to suit our hyper-mediated lives.

Much has been made by Kruger and the exhibition’s organizing institutions that this is an “anti-retrospective.†This is a delicious phrase, and a great bit of marketing. By eschewing a strict chronology or the mythologizing narrative of “greatness†THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU is adamant that it is not trying to cement Kruger’s legacy. Instead, what Kruger and the curatorial teams have put together is a “rethinking, remaking and replaying [of] her work over the decades for the constantly moving present.†There are moments when the show achieves this, especially in the works that reside outside of the museum and infiltrate public spaces. But a few of the newer works and Replays fail to “meet the moment.†They tend to be dense, chatty, and obsessed with re-evaluating their own meaning, rather than truly positioning themselves in a relevant way to contemporary life. While so much of Kruger’s cutting work anticipated the major crises of the twenty-first century, both for the individual and the collective, in many ways the newer works and Replays don’t confront its incomprehensible complexity, scope, and violence. Kruger has made work recently that does succeed in this way; who could forget the full page ad Kruger published in the New York Times at the beginning of the pandemic that read: “A CORPSE IS NOT A CUSTOMER.â€

Kruger’s work thrives when it can be brief, responsive, and immediate, which is perhaps why the traditional notion of a “major retrospective†unnerves her. Kruger may be clever in critiquing the institutions her work sits within, but that placement can also dampen her criticism. The act can feel self-indulgent, especially in comparison to how contemporary artists now are demanding more accountability and transparency from art institutions. Just this month, the MET announced it would be removing the Sackler name from their galleries, in large part due to the protests organized by artist and activist Nan Goldin and her group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). In the past two years, we have come to expect art institutions to engage with the political, social and environmental catastrophes of the twenty-first century, not just be hermetic worlds unto themselves. THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU is an ambitious and rousing exhibition, but the culture has collectively caught up to (and perhaps surpassed) Kruger’s vantage point.

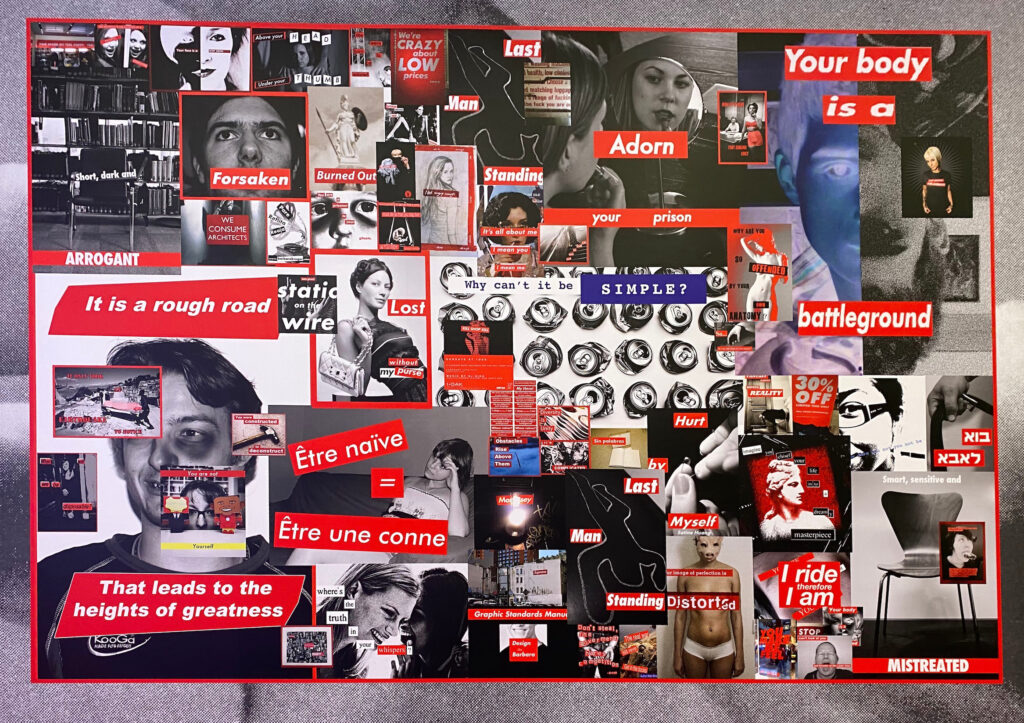

In a rare instance of mainstream cultural crossover, Kruger’s work has made its way into the public consciousness. A few of her aphoristic phrasings have become iconic (“Your Body is a Battleground,†“I Shop Therefore I Amâ€) and her design sensibility has been endlessly aped (most notably by Supreme). Untitled (That’s the Way We Do It), located in the entrance to the main exhibition space, deals with Kruger’s own fascination and bemusement with her style’s impact. To create this work, Kruger compiled 550 images from the internet that “stole†from her work and digitally collaged them in the style of her early paste-ups that she’d put on walls around New York City. That’s the Way We Do It includes riffs of all sorts, usually using Kruger’s iconic block of white Futura Bold text against a red background: store advertisements (“We’re CRAZY about LOW pricesâ€), moody Tumblr posts (“Fuck my lookâ€), Shephard Fairey’s OBEY logo, and lazy imitations (“I shop I amâ€).

The best gem in That’s the Way We Do It is a black and white portrait of Kruger (who has long been against the press reproducing her own likeness), with her features obscured by the text “parody IS NOT infringement.†It is a cheeky refusal, a comment on her own discomfort with associating her face (and thus personal authorship) to her work, and illustrates Kruger’s belief that copyrights are euphemisms for corporate control. The work also lays bare the appetites of capitalism; any earnest attempt at critiquing power structures can be so easily co-opted and repositioned as a slogan, a t-shirt, an ad, an insult, a meme. In That’s the Way We Do It, Kruger ambivalently observes her work taking on a life of its own.

That’s the Way We Do It also introduces some of the less satisfying aspects of the show. The wall-to-wall scale is used frequently throughout the exhibition. While this size often works tremendously well for Kruger’s work (see Untitled (Shafted) at LACMA), in the modest galleries AIC has arranged the show into, the works displayed in this manner are often illegible and deafening. Even when the messages conveyed are worthy of engagement, the overwhelming proximity of them causes disengagement, like a too-loud commercial that makes you change the channel. The material quality of the vinyl, which is used for a good deal of the works, is a turn-off; its low sheen resembles retail window decals. Combine this effect with the fluorescent lighting and institutional gray carpet, and the galleries can start to feel like a pristine department store.

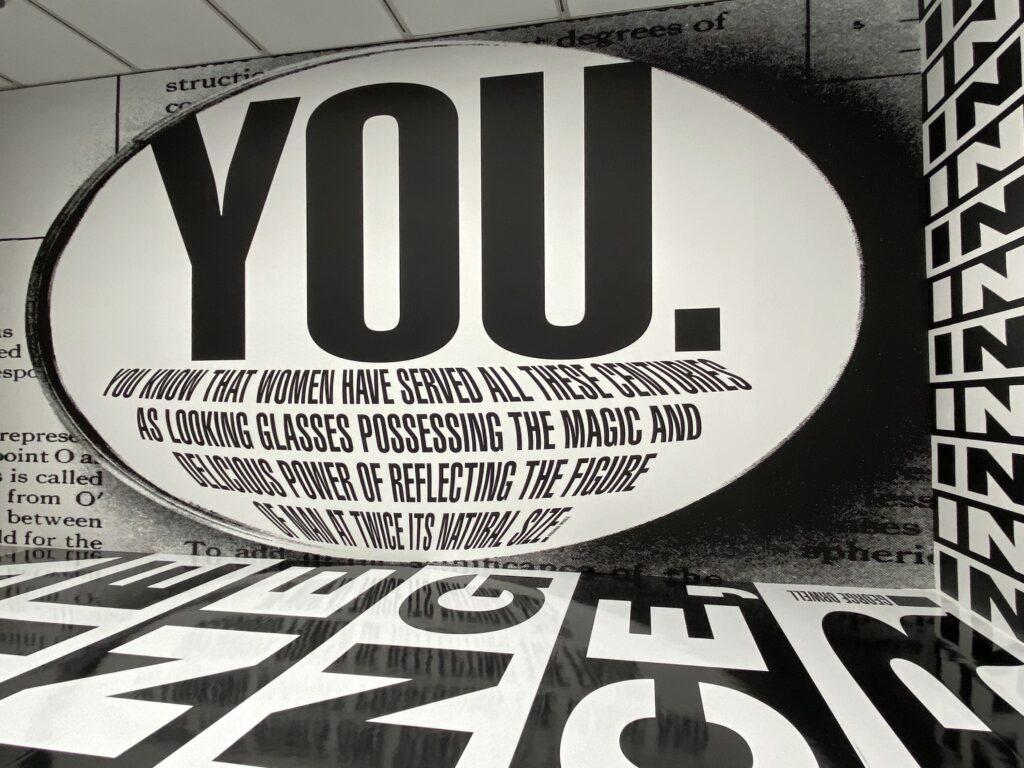

Untitled (Forever) is another such immersive, room-sized work; the black and white text channels the shouting ticker-tape of news headlines (“IN THE END, LIES PREVAIL. IN THE END HOPE IS LOST.â€) and the floor displays a George Orwell quote that Kruger often uses (“IF YOU WANT A PICTURE OF THE FUTURE, IMAGINE A BOOT STOMPING ON A HUMAN FACE, FOREVER.â€).

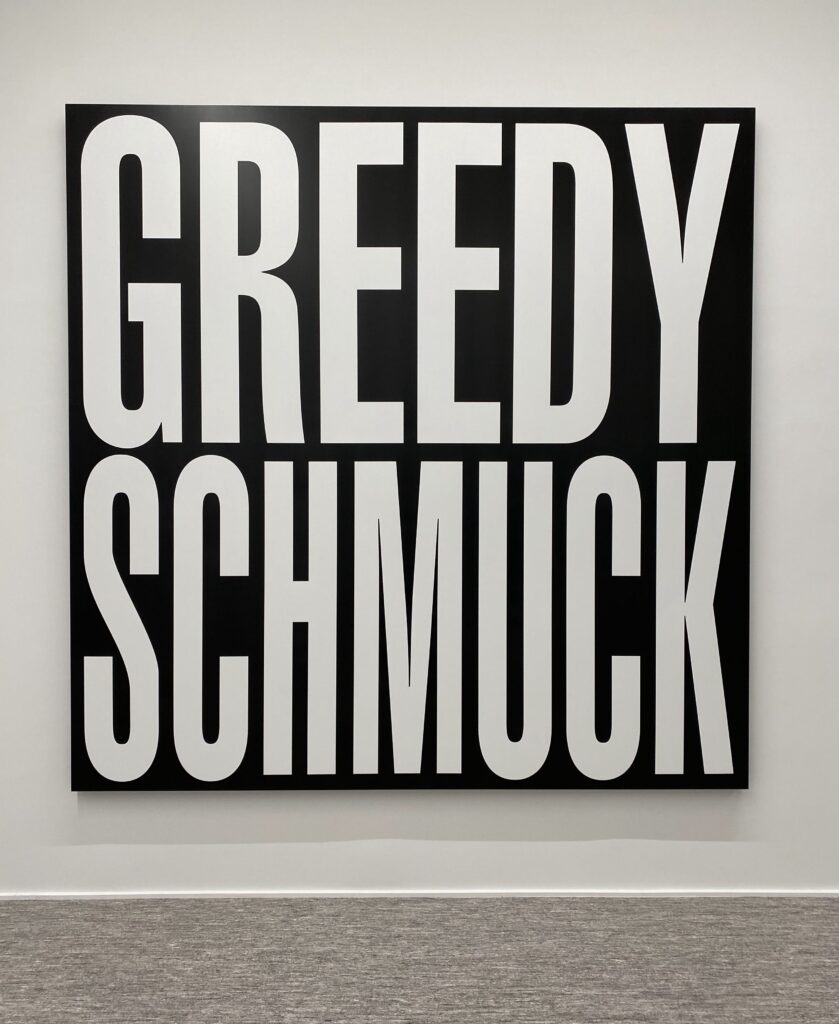

The content of most of the works is not new, yet the points being made still feel urgent. What can be missing in this show at times is the proper context and contrast – this is what usually gives Kruger’s words their weight. Works like Untitled (Greedy Schmuck) and Untitled (Too Big to Fail) fall flat at their gallery-wall-friendly, salable size. The jab of the accusations also misses their mark. Greedy Schmuck first appeared at the entrance of Art Basel Miami in 2012, a far more fitting venue for lobbing such an insult.

The most impactful works of the show are the ones that intervene at an architectural scale. This includes fourteen banners at the Michigan Avenue entrance that read: “PROMISE. PROPERTY. POVERTY. PROFIT. PAIN. POWER. PLEASURE. DENIAL. DECEIT. DISSENT. DELIGHT. DOUBT. DISGUST. DESIRE.†Perhaps the best work of the show – and most easily missed – resides above the Metra train tracks in the windows of the Alsdorf Galleries. Seen from the Nichols Bridgeway, just barely close enough to make out, a banner: “ANOTHER HOPE. ANOTHER FEAR. ANOTHER YEAR.†Skyscrapers peek out from above the building, the sky stretches out overhead, and between you and the ambiguous message lies the expanse of railroad tracks, iron scaffolding, and sandy dirt. It is heartbreaking but strangely comforting, especially as we enter another year of uncertainty in the pandemic. A deep empathy is often ascribed to Kruger’s work, and this is one of the instances in the show where this is truly felt.

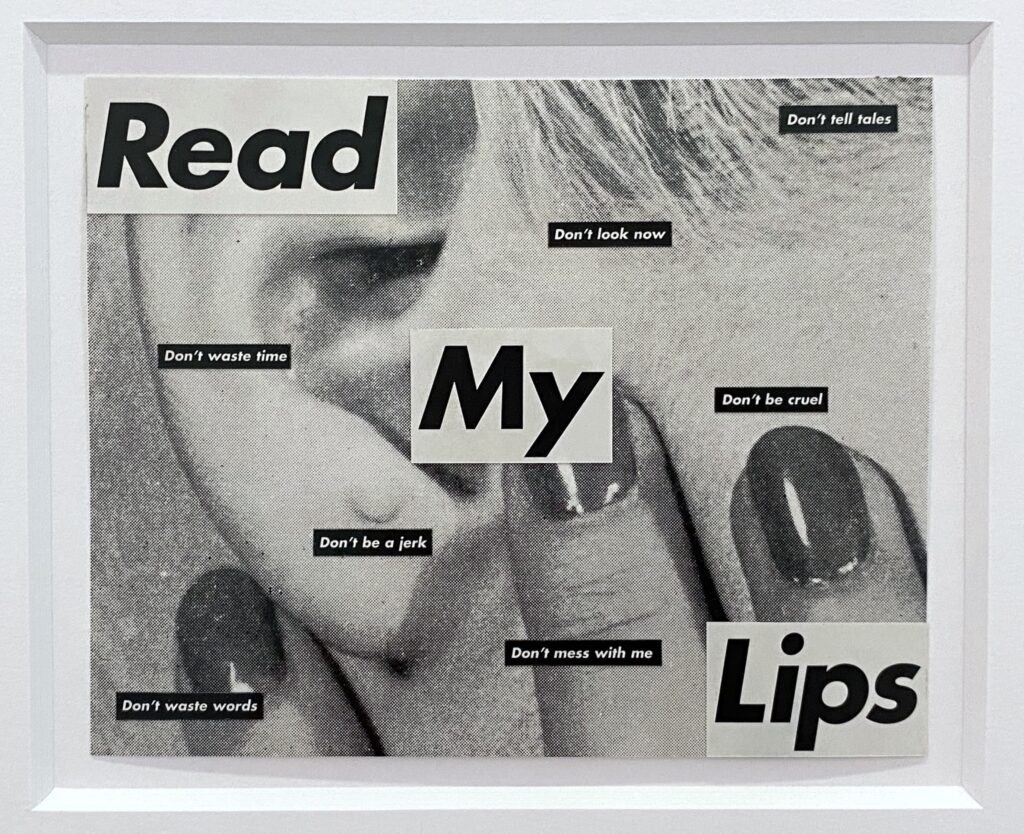

Other stand-out moments include a hallway of Kruger’s stark and biting collages from the 1980s and the 1996 series of PSAs Kruger made while in residence at the Wexner Center for the Arts. The vague but grim thirty-second spots are shown on small vintage TVs placed throughout the museum. Tucked away near grand staircases and headless marble antiquities, the five vignettes espouse Kruger’s golden rules: “It’s Cool to be Kind. Live and Let Live.†“Don’t torture. Don’t hate. Don’t scream. Let it go.â€

The video and audio works in the show are a mixed bag. The “rogue audio†installations in the elevators and the vestibules of the Michigan and Monroe entrances are compelling (a feminine voice repeats “sorry†and “helloâ€), while Untitled (Take Care of Yourself) and Untitled (I Love You), located in the main gallery space, get lost amongst the other works on view. Kruger’s longer, narrative(-ish) videos are projected in rooms by themselves, which gives patrons the chance to sit and experience them, but the Replays and smaller video works tend to interfere with each other.

One notable Replay is the 1987 work Untitled (I Shop Therefore I Am), which is located in the entrance to Regenstein Hall along with That’s the Way We Do It. Kruger turns the once-static collage into a seven-foot-tall LED panel, where the iconic image comes together and falls apart in jigsaw puzzle pieces. Frantic mouse clicks and cash register clangs accompany the work. The text changes with each loud “CHA-CHING,†announcing dictums both deep (“I am therefore I hate,†“I die therefore I wasâ€) and dumb (“I sext therefore I amâ€). The cartoonish but violent sound echoes through the corridor. It is a brutalizing introduction to the exhibition. It makes apparent the ravenous (and destructive) consumption that we have become so good at hiding. The soundtrack to our buying habits is now the comforting “whoosh!†of an Apple Pay transaction, the daffy jingle of the Trader Joe’s card machine, the faceless and frictionless arrival of an Amazon package at our door. Even though the Replays don’t feel entirely revelatory in their glossy new form, they demand your attention, like a car wreck.

For so long, Kruger’s work has prided itself on being egalitarian, accessible, and insurrectionist. And as much as Kruger’s work lampoons the cult of self-obsession, many of the works in this “anti-retrospective†seem to look inward, assessing their own value. In 2013, Kruger told Interview that her work is not informed by the art world. She said that the “closed language†of conceptual art was not part of her work and that she preferred to relate directly to the reader “who doesn’t know the secret code word.†In the past five years though, Kruger’s work seems to have become hyper-focused on the interiority of the art world. An example of this is Untitled (Artforum), a didactic video Kruger made in 2016 for the super-insider publication, for which she was a staff writer. In the work, Kruger edits her editor, marking up an article in the magazine with her own pink addendums. She critiques Artforum for co-opting the language of capitalism to sell its high-culture brand. It is a smart and brattish work, but also insufferable, even for those in on the joke. In being able to make these critiques (and get them published) Kruger is wielding the very privilege she abhors. This makes the work feel, ultimately, toothless – what’s really at stake? Who does she speak for?

In another work, Kruger preempts any skepticism to be had over a work like Untitled (Artforum), or even the exhibition as a whole. Advertisements for Myself (Project for the New York Times), a wall-sized vinyl work, lists all of the nasty (and flattering) things that could be said of Kruger: “BLAZINGLY ACCURATE,†“A TIRED HACK,†“A MAJOR ARTIST,†“TOTALLY CLUELESS,†“A GREAT DANCER,†and “INSANELY SELF-CONSCIOUS.†The act of printing, in foot-high font, what everyone thinks of you, seems unshakably demented, but also puts Kruger ahead: I know what you think of me, and I do not care (but I do). This work also gets at a guiding ethos of Kruger’s recent work, which she shared in The Art Newspaper when the exhibition opened: “Digital life has been emancipating and liberatory but at the same time it’s haunting and damaging and punishing and everything in between. It’s enabled the best and the worst of us.â€

Ultimately, the exhibition accomplishes what it sets out to do: you part with a feeling of agitation, dis-ease, and futility. You reenter the world smaller. Your phone seems even more acutely evil. The buildings of the city loom larger, and the possibility that things will change seems further away. Kruger’s work will continue to be important as long as “the world is in shambles†(as her work Untitled (No Comment) concludes). So little art is great merely because it exposes the unvarnished truth, with no intervening nuance or forward-looking vision of the future. In the New York Times in 1990, commenting on the debate between high and low culture, Kruger wrote: “Times have changed, and the world comes to us in different ways.†In 2021, THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU may be missing the ways the world now comes to us. In a time of such urgent, interlocking crises, it is easy to be against so much – but what kind of change is Kruger for?

*******

THINKING OF YOU. I MEAN ME. I MEAN YOU is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago until January 24, 2022. The exhibition will travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and The Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) in 2022 and 2023. www.artic.edu

Photography by Ely Maris